Germany. A Winter's Tale

Ein Wintermärchen) is a satirical epic poem by the German writer Heinrich Heine (1797–1856), describing the thoughts of a journey from Paris to Hamburg the author made in winter 1843.

Wintermärchen and Winterreise Heinrich Heine was a master of the natural style of lyrics on the theme of love, like those in the 'Lyrisches Intermezzo' of 1822-1823 in Das Buch der Lieder (1827) which were set by Robert Schumann in his Dichterliebe.

Yet Heine's work addressed political preoccupations with a barbed and contemporary voice, whereas Müller's melancholy lyricism and nature-scenery explored more private (if equally universal) human experience.

In Section III, full of euphoria he sets foot again on German soil, with only ‘shirts, trousers and pocket handkerchiefs’ in his luggage, but in his head ‘a twittering birds’-nest/ of books liable to be confiscated’.

In Aachen Heine first comes in contact again with the Prussian military: These people are still the same wooden types,Spout pedantic commonplaces -All motions right-angled - and priggishnessIs frozen upon their faces.

That the anachronistic building works came to be discontinued in the course of the Reformation indicated for the poet a positive advance: the overcoming of traditional ways of thought and the end of spiritual juvenility or adolescence.

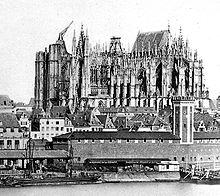

At last he reaches the Cathedral with the Three Kings Shrine, and “smashes up the poor skeletons of Superstition.’ In Section VIII he travels further on to Hagen and Mülheim, places which bring to mind his former enthusiasm for Napoleon Bonaparte.

In Section XI he travels through the Teutoburg Forest and fantasizes about what might have happened if Hermann of the Cherusci had not there vanquished the Roman army under Publius Quinctilius Varus and ended both colonialism and Romanisation east of the Rhine River.

Otherwise, Romanitas and the depravity of the Roman nobility described by Seutonius and Tacitus would have permeated to the spiritual core of the German people, and in place of the ‘Three Dozen Fathers of the Provinces’ there would have been by now at least one proper Nero.

The Section is also a disguised attack on the preference for Neoclassicism in the Kingdom of Prussia by the ‘Romantic on the Throne,’ Friedrich Wilhelm IV; and against the significant individuals in this movement (for example Raumer, Hengstenberg, Birch-Pfeiffer, Schelling, Maßmann, Cornelius), who all lived in Berlin.

In direct contrast to Lewis H. Lapham's counterfactual history essay in the 1999 volume What If?, which attempted to draw a straight line of cause and effect between the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 A.D. and the Nazi war crimes of the 20th-century, Heine ends by instead expressing gratitude for the decolonisation of the province of Germania Antiqua under the leadership of Hermann and proudly reports his own decision to become of the first to donate money towards the building of the Hermannsdenkmal.

From there he went on to a meeting with King Ernest Augustus of Hanover in that place, who, "accustomed to life in Great Britain" detains him for a deadly length of time.

A solemn promise of the greatest secrecy must be made in Old Testament fashion, in which he places his hand under the thigh of the Goddess (she blushes slightly – having been drinking rum!).

In the final stanzas Heine places himself in the tradition of Aristophanes and Dante and speaks directly to the King of Prussia: Then do not harm your living bards, For they have fire and arms More frightful than Jove’s thunderbolt: Through them the Poet forms.

Ein Wintermärchen shows Heine’s world of images and his folk-song-like poetic diction in a compact gathering, with cutting, ironic criticisms of the circumstances in his homeland.

He did not see himself as an enemy of Germany, but rather as a critic out of love for the Fatherland: Plant the black, red, gold banner at the summit of the German idea, make it the standard of free mankind, and I will shed my dear heart’s blood for it.

Immediately after World War II a cheap edition of the poem with Heine’s Foreword and an introduction by Wolfgang Goetz was published by the Wedding-Verlag in Berlin in 1946.

A great deal of the attraction which the verse-epic holds today is grounded in this, that its message is not one-dimensional, but rather brings into expression the many-sided contradictions or contrasts in Heine’s thought.

This exemplified the visible breach which the French July Revolution of 1830 signifies for intellectual Germany: the fresh breeze of freedom suffocated in the reactionary exertions of the Metternich Restoration, the soon-downtrodden ‘Spring’ of freedom yielded to a new winter of censorship, repression, persecution and exile; the dream of a free and democratic Germany was for a whole century dismissed from the realm of possibility.

Ein Wintermärchen is a high-point of political poetry of the Vormärz period before the March Revolution of 1848, and in Germany is part of the official educational curriculum.

The work taken for years and decades as the anti-German pamphlet of the ‘voluntary Frenchman’ Heine, today is for many people the most moving poem ever written by an emigrant.

Recently, reference to this poem has been made by director Sönke Wortmann for his football documentary on the German male national team during the 2006 FIFA world cup.

The world cup in 2006 is often mentioned as a point in time which had a significant positive impact on modern Germany, reflecting a changed understanding of national identity which has been evolving continuously over the 50 years prior to the event.