Lisztomania

This frenzy first occurred in Berlin in 1841 and the term was later coined by Heinrich Heine in a feuilleton he wrote on 25 April 1844, discussing the 1844 Parisian concert season.

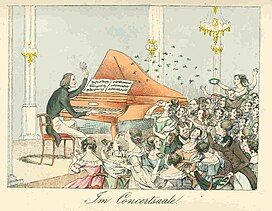

Lisztomania was characterized by intense levels of hysteria demonstrated by fans, akin to the treatment of some celebrity musicians starting in the second half of the 20th century – but in a time not known for such musical excitement.

Franz Liszt began receiving piano lessons at the age of seven from his father Adam Liszt, a talented musician who played the piano, violin, cello, and guitar, and who knew Joseph Haydn, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, and Ludwig van Beethoven personally.

[2] According to one report:Liszt once threw away an old cigar stump in the street under the watchful eyes of an infatuated lady-in-waiting, who reverently picked the offensive weed out of the gutter, had it encased in a locket and surrounded with the monogram "F.L."

[4]The writer Heinrich Heine coined the term Lisztomania to describe the outpouring of emotion that accompanied Liszt and his performances.

His review of the musical season of 1844, written in Paris on 25 April 1844, is the first place where he uses the term Lisztomania: When formerly I heard of the fainting spells which broke out in Germany and specially in Berlin, when Liszt showed himself there, I shrugged my shoulders pityingly and thought: quiet sabbatarian Germany does not wish to lose the opportunity of getting the little necessary exercise permitted it...

[5]Musicologist Dana Gooley argues that Heine's use of the term "Lisztomania" was not used in the same way that "Beatlemania" was used to describe the intense emotion generated towards The Beatles in the 20th century.

[6]In 1891, American poet Nathan Haskell Dole used the term in a relatively neutral context, to describe pianists' momentary fixation on Liszt's compositions:It is therefore not an uncommon phenomenon to see pianists outgrowing their Liszt enthusiasms and to look back upon their "Lisztomania" as only a phase of development, of which they are not ashamed, but rather proud.

A physician, whose specialty is female diseases, and whom I asked to explain the magic our Liszt exerted upon the public, smiled in the strangest manner, and at the same time said all sorts of things about magnetism, galvanism, electricity, of the contagion of the close hall filled with countless wax lights and several hundred perfumed and perspiring human beings, of historical epilepsy, of the phenomenon of tickling, of musical cantherides, and other scabrous things, which, I believe have reference to the mysteries of the bona dea.

It seems to me at times that all this sorcery may be explained by the fact that no one on earth knows so well how to organize his successes, or rather their mise en scene, as our Franz Liszt.