Dacians

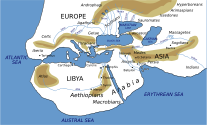

[3][4][5] This area includes mainly the present-day countries of Romania and Moldova, as well as parts of Ukraine,[6] Eastern Serbia, Northern Bulgaria, Slovakia,[7] Hungary and Southern Poland.

By the end of the first century AD, all the inhabitants of the lands which now form Romania were known to the Romans as Daci, with the exception of some Celtic and Germanic tribes who infiltrated from the west, and Sarmatian and related people from the east.

[53] Another etymology, linked to the Proto-Indo-European language roots *dhe- meaning "to set, place" and dheua → dava ("settlement") and dhe-k → daci is supported by Romanian historian Ioan I. Russu (1967).

[54] Mircea Eliade attempted, in his book From Zalmoxis to Genghis Khan, to give a mythological foundation to an alleged special relation between Dacians and the wolves:[55] Evidence of proto-Thracians or proto-Dacians in the prehistoric period depends on the remains of material culture.

a larger territory than Ptolemaic Dacia,[clarification needed] stretching between Bohemia in the west and the Dnieper cataracts in the east, and up to the Pripyat, Vistula, and Oder rivers in the north and northwest.

[69] According to Strabo's Geographica, written around AD 20,[74] the Getes (Geto-Dacians) bordered the Suevi who lived in the Hercynian Forest, which is somewhere in the vicinity of the river Duria, the present-day Váh (Waag).

Georgiev also claimed that names from approximately Roman Dacia and Moesia show different and generally less extensive changes in Indo-European consonants and vowels than those found in Thrace itself.

[112] In about 140 AD, Ptolemy lists the names of several tribes residing on the fringes of the Roman Dacia (west, east and north of the Carpathian range), and the ethnic picture seems to be a mixed one.

[125] Based on the account of Dio Cassius, Heather (2010) considers that Hasding Vandals, around 171 AD, attempted to take control of lands which previously belonged to the free Dacian group called the Costoboci.

[130] This indication of the socio-familial line of descent seen also in other inscriptions (i.e. Diurpaneus qui Euprepes Sterissae f(ilius) Dacus) is a custom attested since the historical period (beginning in the 5th century BC) when Thracians were under Greek influence.

[136] According to Heather (2010), the Carpi were Dacians from the eastern foothills of the Carpathian range – modern Moldavia and Wallachia – who had not been brought under direct Roman rule at the time of Trajan's conquest of Transylvania Dacia.

[139][140] A quote from the 6th-century Byzantine chronicler Zosimus referring to the Carpo-Dacians (Greek: Καρποδάκαι, Latin: Carpo-Dacae), who attacked the Romans in the late 4th century, is seen as evidence of their Dacian ethnicity.

On the whole, the Bronze Age witnessed the evolution of the ethnic groups which emerged during the Eneolithic period, and eventually the syncretism of both autochthonous and Indo-European elements from the steppes and the Pontic regions.

[145] The first written mention of the name "Dacians" is in Roman sources, but classical authors are unanimous in considering them a branch of the Getae, a Thracian people known from Greek writings.

[145] Linguist Vladimir Georgiev says that based on the absence of toponyms ending in dava in Southern Bulgaria, the Moesians and Dacians (or as he calls them Daco-Mysians) couldn't be related to the Thracians.

Together with the original domestic population, they created the Puchov culture that spread into central and northern Slovakia, including Spis, and penetrated northeastern Moravia and southern Poland.

In 72 BC, his troops occupied the Greek coastal cities of Scythia Minor (the modern Dobrogea region in Romania and Bulgaria), which had sided with Rome's Hellenistic arch-enemy, king Mithridates VI of Pontus, in the Third Mithridatic War.

These were held in a powerful fortress called Genucla (Isaccea, near modern Tulcea, in the Danube delta region of Romania), controlled by Zyraxes, the local Getan petty king.

[190] Emperor Trajan (ruled 98–117 AD) opted for a different approach and decided to conquer the Dacian kingdom, partly in order to seize its vast gold mines wealth.

[192] Only about half part of Dacia then became a Roman province,[193] with a newly built capital at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, 40 km away from the site of Old Sarmisegetuza Regia, which was razed to the ground.

Aurelian made this decision on account of counter-pressures on the Empire there caused by the Carpi, Visigoths, Sarmatians, and Vandals; the lines of defence needed to be shortened, and Dacia was deemed not defensible given the demands on available resources.

[173] It is not possible to discern how many civilians followed the army out of Dacia; it is clear that there was no mass emigration, since there is evidence of continuity of settlement in Dacian villages and farms; the evacuation may not at first have been intended to be a permanent measure.

[204] As late as AD 300, the tetrarchic emperors had resettled tens of thousands of Dacian Carpi inside the empire, dispersing them in communities the length of the Danube, from Austria to the Black Sea.

Early in the 1st century BC, the Dacians replaced these with silver denarii of the Roman Republic, both official coins of Rome exported to Dacia, as well as locally made imitations of them.

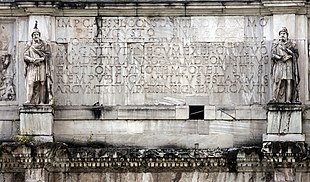

Dacians had developed the murus dacicus (double-skinned ashlar-masonry with rubble fill and tie beams) characteristic to their complexes of fortified cities, like their capital Sarmizegetusa Regia in what is today Hunedoara County, Romania.

[206] This type of wall has been discovered not only in the Dacian citadel of the Orastie mountains, but also in those at Covasna, Breaza near Făgăraș, Tilișca near Sibiu, Căpâlna in the Sebeș valley, Bănița not far from Petroșani, and Piatra Craivii to the north of Alba Iulia.

in reality, the creation of the Dacian ethnos was foreshadowed by migratory movements from the lower Danube region following the collapse of the Celtic cultural circle c. 300 BC (The grave with a helmet from Ciumeşti – 50 years from its discovery.

Old and new discoveries) Specific Dacian material culture includes: wheel-turned pottery that is generally plain but with distinctive elite wares, massive silver dress fibulae, precious metal plate, ashlar masonry, fortifications, upland sanctuaries with horseshoe-shaped precincts, and decorated clay heart altars at settlement sites.

The ancient languages of these people became extinct, and their cultural influence highly reduced, after the repeated invasions of the Balkans by Celts, Huns, Goths, and Sarmatians, accompanied by persistent hellenization, romanisation and later slavicisation.

[14][229] Strabo wrote about the high priest of King Burebista Deceneus: "a man who not only had wandered through Egypt, but also had thoroughly learned certain prognostics through which he would pretend to tell the divine will; and within a short time he was set up as god (as I said when relating the story of Zamolxis).