Getter

To avoid being contaminated by the atmosphere, the getter must be introduced into the vacuum system in an inactive form during assembly, and activated after evacuation.

Large transmission tubes and specialty systems often use more exotic getters, including aluminium, magnesium, calcium, sodium, strontium, caesium, and phosphorus.

If the getter is exposed to atmospheric air (for example, if the tube breaks or develops a leak), it turns white and becomes useless.

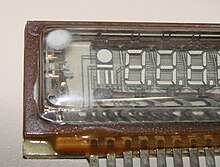

A white deposit, usually barium oxide, indicates total failure of the seal on the vacuum system, as shown in the fluorescent display module depicted above.

The typical flashed getter used in small vacuum tubes (seen in 12AX7 tube, top) consists of a ring-shaped structure made from a long strip of nickel, which is folded into a long, narrow trough, filled with a mixture of barium azide and powdered glass, and then folded into the closed ring shape.

The getter is attached with its trough opening facing upward toward the glass, in the specific case depicted above.

The nitrogen is pumped out and the barium condenses on the bulb above the plane of the ring forming a mirror-like deposit with a large surface area.

The powdered glass in the ring melts and entraps any particles which could otherwise escape loose inside the bulb causing later problems.

Common alloys have names of the form St (Stabil) followed by a number: In tubes used in electronics, the getter material coats plates within the tube which are heated in normal operation; when getters are used within more general vacuum systems, such as in semiconductor manufacturing, they are introduced as separate pieces of equipment in the vacuum chamber, and turned on when needed.

Deposited and patterned getter material is being used in microelectronics packaging to provide an ultra-high vacuum in a sealed cavity.

- (center) A vacuum tube with a flashed getter coating on the inner surface of the top of the tube.

- (left) The inside of a similar tube, showing the reservoir that holds the material that is evaporated to create the getter coating. During manufacture, after the tube is evacuated and sealed, an induction heater evaporates the material, which condenses on the glass.