Gibbs phenomenon

In mathematics, the Gibbs phenomenon is the oscillatory behavior of the Fourier series of a piecewise continuously differentiable periodic function around a jump discontinuity.

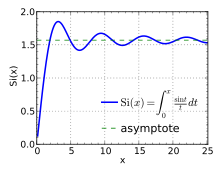

As more sinusoids are used, this approximation error approaches a limit of about 9% of the jump, though the infinite Fourier series sum does eventually converge almost everywhere.

[1] The Gibbs phenomenon was observed by experimental physicists and was believed to be due to imperfections in the measuring apparatus,[2] but it is in fact a mathematical result.

The Gibbs phenomenon is a behavior of the Fourier series of a function with a jump discontinuity and is described as the following:As more Fourier series constituents or components are taken, the Fourier series shows the first overshoot in the oscillatory behavior around the jump point approaching ~ 9% of the (full) jump and this oscillation does not disappear but gets closer to the point so that the integral of the oscillation approaches zero.At the jump point, the Fourier series gives the average of the function's both side limits toward the point.

The three pictures on the right demonstrate the Gibbs phenomenon for a square wave (with peak-to-peak amplitude of

), the error of the partial Fourier series converges to a fixed height.

More generally, at any discontinuity of a piecewise continuously differentiable function with a jump of

[6] The paper attracted little attention until 1914 when it was mentioned in Heinrich Burkhardt's review of mathematical analysis in Klein's encyclopedia.

[7] In 1898, Albert A. Michelson developed a device that could compute and re-synthesize the Fourier series.

[8] A widespread anecdote says that when the Fourier coefficients for a square wave were input to the machine, the graph would oscillate at the discontinuities, and that because it was a physical device subject to manufacturing flaws, Michelson was convinced that the overshoot was caused by errors in the machine.

In fact the graphs produced by the machine were not good enough to exhibit the Gibbs phenomenon clearly, and Michelson may not have noticed it as he made no mention of this effect in his paper (Michelson & Stratton 1898) about his machine or his later letters to Nature.

[9] Inspired by correspondence in Nature between Michelson and A. E. H. Love about the convergence of the Fourier series of the square wave function, J. Willard Gibbs published a note in 1898 pointing out the important distinction between the limit of the graphs of the partial sums of the Fourier series of a sawtooth wave and the graph of the limit of those partial sums.

In 1899 he published a correction in which he described the overshoot at the point of discontinuity (Nature, April 27, 1899, p. 606).

In 1906, Maxime Bôcher gave a detailed mathematical analysis of that overshoot, coining the term "Gibbs phenomenon"[10] and bringing it into widespread use.

[9] After the existence of Henry Wilbraham's paper became widely known, in 1925 Horatio Scott Carslaw remarked, "We may still call this property of Fourier's series (and certain other series) Gibbs's phenomenon; but we must no longer claim that the property was first discovered by Gibbs.

"[11] Informally, the Gibbs phenomenon reflects the difficulty inherent in approximating a discontinuous function by a finite series of continuous sinusoidal waves.

It is important to put emphasis on the word finite, because even though every partial sum of the Fourier series overshoots around each discontinuity it is approximating, the limit of summing an infinite number of sinusoidal waves does not.

[4] The Gibbs phenomenon is closely related to the principle that the smoothness of a function controls the decay rate of its Fourier coefficients.

Fourier coefficients of smoother functions will more rapidly decay (resulting in faster convergence), whereas Fourier coefficients of discontinuous functions will slowly decay (resulting in slower convergence).

This only provides a partial explanation of the Gibbs phenomenon, since Fourier series with absolutely convergent Fourier coefficients would be uniformly convergent by the Weierstrass M-test and would thus be unable to exhibit the above oscillatory behavior.

[14] Also, using the discrete wavelet transform with Haar basis functions, the Gibbs phenomenon does not occur at all in the case of continuous data at jump discontinuities,[15] and is minimal in the discrete case at large change points.

In the polynomial interpolation setting, the Gibbs phenomenon can be mitigated using the S-Gibbs algorithm.

This can be represented as convolution of the original signal with the impulse response of the filter (also known as the kernel), which is the sinc function.

For the step function, the magnitude of the undershoot is thus exactly the integral of the left tail until the first negative zero: for the normalized sinc of unit sampling period, this is

This is a general feature of the Fourier transform: widening in one domain corresponds to narrowing and increasing height in the other.

is the number of non-zero sinusoidal Fourier series components so there are literatures using

In MRI, the Gibbs phenomenon causes artifacts in the presence of adjacent regions of markedly differing signal intensity.

This is most commonly encountered in spinal MRIs where the Gibbs phenomenon may simulate the appearance of syringomyelia.

When periodic boundary conditions are imposed in the Fourier transform, this jump discontinuity is represented by continuum of frequencies along the axes in reciprocal space (i.e. a cross pattern of intensity in the Fourier transform).

Thus for instance because idealized brick-wall and rectangular filters have discontinuities in the frequency domain, their exact representation in the time domain necessarily requires an infinitely-long sinc filter impulse response, since a finite impulse response will result in Gibbs rippling in the frequency response near cut-off frequencies, though this rippling can be reduced by windowing finite impulse response filters (at the expense of wider transition bands).