Giganotosaurus

Giganotosaurus (/ˌɡɪɡəˌnoʊtəˈsɔːrəs/ GIG-ə-NOH-tə-SOR-əs[2]) is a genus of large theropod dinosaur that lived in what is now Argentina, during the early Cenomanian age of the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 99.6 to 95 million years ago.

Part of the family Carcharodontosauridae, Giganotosaurus is one of the most completely known members of the group, which includes other very large theropods, such as the closely related Mapusaurus, Tyrannotitan and Carcharodontosaurus.

In 1993, the amateur Argentine fossil hunter Rubén Darío Carolini [es] discovered the tibia (lower leg bone) of a theropod dinosaur while driving a dune buggy in the badlands near Villa El Chocón, in the Neuquén province of Patagonia, Argentina.

[3][4] The discovery was announced by the paleontologists Rodolfo Coria and Leonardo Salgado at a Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in 1994, where science writer Don Lessem offered to fund the excavation, after having been impressed by a photo of the leg-bone.

The specimen preserved almost 70% of the skeleton, and included most of the vertebral column, the pectoral and pelvic girdles, the femora, and the left tibia and fibula.

[6][1] In 1995, this specimen was preliminarily described by Coria and Salgado, who made it the holotype of the new genus and species Giganotosaurus carolinii (parts of the skeleton were still encased in plaster at this time).

[1][7] The holotype skeleton is now housed in the Ernesto Bachmann Paleontological Museum (where it is catalogued as specimen MUCPv-Ch1) in Villa El Chocón, which was inaugurated in 1995 at the request of Carolini.

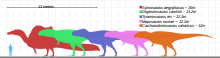

[4][8] One of the features of theropod dinosaurs that has attracted most scientific interest is the fact that the group includes the largest terrestrial predators of the Mesozoic Era.

[1] In 1996, the paleontologist Paul Sereno and colleagues described a new skull of the related genus Carcharodontosaurus from Morocco, a theropod described in 1927 but previously known only from fragmentary remains (much of its fossils were destroyed in World War II).

[9] In an interview for a 1995 article entitled "new beast usurps T. rex as king carnivore", Sereno noted that these newly discovered theropods from South America and Africa competed with Tyrannosaurus as the largest predators, and would help in the understanding of Late Cretaceous dinosaur faunas, which had otherwise been very "North America-centric".

[12] In 1998, the paleontologist Jorge O. Calvo and Coria assigned a partial left dentary bone (part of the lower jaw) containing some teeth (MUCPv-95) to Giganotosaurus.

[13][14][15] In 1999, Calvo referred an incomplete tooth, (MUCPv-52), to Giganotosaurus; this specimen was discovered near Lake Ezequiel Ramos Mexia in 1987 by A. Delgado, and is therefore the first known fossil of the genus.

Calvo further suggested that some theropod trackways and isolated tracks (which he made the basis of the ichnotaxon Abelichnus astigarrae in 1991) belonged to Giganotosaurus, based on their large size.

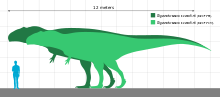

[16] In their 2002 description of the braincase of Giganotosaurus, Coria and Currie gave a length estimate of 1.60 m (5 ft) for the holotype skull, and calculated a weight of 4.2 t (4.6 short tons) by extrapolating from the 520 mm (20 in) circumference of the femur-shaft.

[6] In 2004, the paleontologist Gerardo V. Mazzetta and colleagues pointed out that though the femur of the Giganotosaurus holotype was larger than that of "Sue", the tibia was 8 cm (3 in) shorter at 1.12 m (4 ft).

[17] In 2005, the paleontologist Cristiano Dal Sasso and colleagues described new skull material (a snout) of Spinosaurus (the original fossils of which were also destroyed during World War II), and concluded this dinosaur would have been 16 to 18 m (52 to 59 ft) long with a weight 7 to 9 t (7.7 to 9.9 short tons), exceeding the maximum size of all other theropods.

[21] In 2012, the paleontologist Matthew T. Carrano and colleagues noted that though Giganotosaurus had received much attention due to its enormous size, and in spite of the holotype being relatively complete, it had not yet been described in detail, apart from the braincase.

[22] In 2013, the paleontologist Scott Hartman published a Graphic Double Integration mass estimate (based on drawn skeletal reconstructions) on his blog, wherein he found Tyrannosaurus ("Sue") to have been larger than Giganotosaurus overall.

The neck muscles that elevated the head would have attached to the prominent supraoccipital bones on the top of the skull, which functioned like the nuchal crest of tyrannosaurs.

[1] The ilium of the pelvis had a convex upper border, a low postacetabular blade (behind the acetabulum), and a narrow brevis-shelf (a projection where tail muscles attached).

The tibia of the lower leg was expanded at the upper end, its articular facet (where it articulated with the femur) was wide, and its shaft was compressed from front to back.

Features shared between these genera include the lacrimal and postorbital bones forming a broad "shelf" over the orbit, and the squared front end of the lower jaw.

[36] In 2006, Coria and Currie united Giganotosaurus and Mapusaurus in the carcharodontosaurid subfamily Giganotosaurinae based on shared features of the femur, such as a weak fourth trochanter, and a shallow, broad groove on the lower end.

Dispersal routes between the northern and southern continents appear to have been severed by ocean barriers in the Late Cretaceous, which led to more distinct, provincial faunas, by preventing exchange.

[9] Previously, it was thought that the Cretaceous world was biogeographically separated, with the northern continents being dominated by tyrannosaurids, South America by abelisaurids, and Africa by carcharodontosaurids.

[11][39] The subfamily Carcharodontosaurinae, in which Giganotosaurus belongs, appears to have been restricted to the southern continent of Gondwana (formed by South America and Africa), where they were probably the apex (top) predators.

These thermoregulatory patterns indicate that these dinosaurs had a metabolism intermediate between that of mammals and reptiles, and were therefore homeothermic (with a stable core body-temperature, a type of "warm-bloodedness").

[19] In a 2006 National Geographic article, Coria stated that the bonebed was probably the result of a catastrophic event and that the presence of mainly medium-sized individuals, with very few young or old, is normal for animals that form packs.

[44] Giganotosaurus was discovered in the Candeleros Formation, which was deposited during the Early Cenomanian age of the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 99.6 to 97 million years ago.

The formation is composed of coarse and medium-grained sandstones deposited in a fluvial environment (associated with rivers and streams), and in aeolian conditions (effected by wind).