Gil Vicente

He rose to prominence as a playwright largely on account of the influence of Queen Dowager Leonor, who noticed him as he participated in court dramas and subsequently commissioned him to write his first theatrical work.

While many of Vicente's works were composed to celebrate religious and national festivals or to commemorate events in the life of the royal family, others draw upon popular culture to entertain, and often to critique, Portuguese society of his day.

Faced with social instability in the city Gil Vicent, reportedly, personally defused the situation while scolding the friars for their fear-mongering in a powerfully written letter to King John III, and possibly averting a massacre of Jews and recent converts to Christianity.

[8] Because of the influence of Queen Leonor, who would become his greatest patron in the years to come, Gil Vicente realized that his talent would allow him to do much more than simply adapt his first work for similar occasions.

In 1521, he began serving John III of Portugal, and soon achieved the social status necessary to satirize the clergy and nobility with impunity.

Though himself both actor and author, Gil Vicente had no regular company of players, but it is probable that he easily found students and court servants willing to get up a part for a small fee, especially as the plays would not ordinarily run for more than one night.

[8] Many works about Gil Vicente associate him with a goldsmith of the same name at the court of Évora;[9] technical terms used by the playwright lend credibility to this identification.

Teófilo Braga, who initially believed them to be the same man, later adopted a different opinion after reading a study by Sanches de Baena which showed the different genealogy of two individuals named Gil Vicente.

The masterpiece of Vicente the goldsmith's art was the monstrance of Belém made for the Jerónimos Monastery in 1506, which was crafted from the first gold exported from Mozambique.

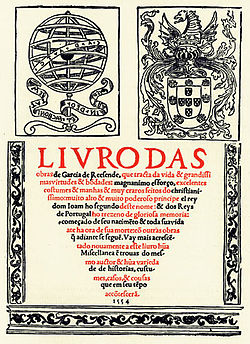

[7] He was also a noted lyric poet in both Portuguese and Spanish,[9] as represented by several poems in the Cancioneiro of Garcia de Resende.

Some of his works are profoundly religious, while other are particularly satirical, particularly when commenting upon what Vicente perceived as the corruption of the clergy and the superficial glory of empire which concealed the increasing poverty of Portugal's lower classes.

Pastoral themes present in the writings of Juan del Encina strongly influenced Vicente's early works and continued to inform his later, more sophisticated plays.

However, many of his works blend both secular and sacred elements; for example, Triologia das Barcas ("Trilogy of the Ships") contains both farcical and religious motifs.

His satires were severely critical, anticipating Jean-Baptiste de Santeul's later epigram (often mistakenly attributed to Horace or Molière), castigat ridendo mores ("[Comedy] criticises customs through humour").

The first world is the abstract, an ideal place of serenity and divine love that leads to inner peace, quietness, and "resplendent glory", according to his letter to John III of Portugal.

Though critics call attention to these anachronisms and narrative inconsistencies, it's possible that Vicente considered these errors trivial in his portrayals of an already false and imperfect world.

Unlike plays which echo Manichaeism by presenting the dichotomy of darkness and light, Vicente's work juxtaposes the two elements in order to illustrate the necessity of both.

Christmas eve, one of his common motifs, is symbolic of his philosophical and religious views: the great darkness borders the divine glory of maternity, birth, forgiveness, serenity, and good will.

Though his patriotism is apparent in works such as Exortação da Guerra ("Exhortation of War") and Auto da Fama ("Act of Fame"), or Cortes de Júpiter ("Courts of Jupiter"), it doesn't merely glorify the Portuguese Empire; instead, it is critical and ethically concerned, especially with the newly available vices which arose due to commerce with the East, that brought a sudden enrichment and disruption of the social fabric.

These plays combine morality narratives with criticism of 16th-century Portuguese society by placing stereotypical characters on a dock to await the arrival of one of the ships which will take them to their eternal destination.

The characters are of a variety of social statuses; for example, in Auto da Barca do Inferno, those awaiting passage include a nobleman, a madam, a corrupt judge and prosecutor, a dissolute friar, a dishonest shoemaker, a hanged man, and a Jew (who would have been considered bound for Hell in Vicente's time).

During the reign of Sancho I of Portugal (1185–1212), Bonamis and Acompaniado, the first recorded Portuguese actors, put on a show of arremedillo and were paid by the King with the donation of lands.

In 1451, theatrical acts accompanied the festivities of the wedding of Infanta (Princess) Eleanor of Portugal with Emperor Frederick III of Habsburg.

For example, Rui de Pina refers to one instance in which King John II himself played the part of The Knight of the Swan in a production which included a scene constructed of fabric waves.

During the action, a fleet of carracks with a crew of spectacularly dressed actors entered the room accompanied by the sound of minstrels, trumpets, kettledrum, and artillery.

Garcia de Resende, in his Cancioneiro Geral, designates a few other works, such as Entremez do Anjo by D. Francisco of Portugal, Count of Vimioso, and the lays of Anrique da Mota.

Since that time, various composers, such as Max Bruch (who made Von den Rosen komm' ich (Von dem Rosenbusch, o Mutter) from Vicente's De la rosa vengo my madre [from the rose I come my mother], which also had a version by Schumann) and Robert Schumann (who made his Spanische Liebeslieder [Spanish Love Songs] no.

Weh, wie zornig ist das Mädchen from Vicente's Sañosa está la nina [Irritated is the little girl] and no.

Alfredo Roque Gameiro .