Gilan province

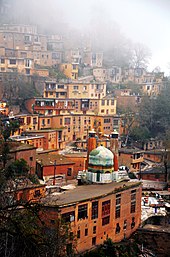

Other cities include Astaneh-ye Ashrafiyeh, Astara, Fuman, Hashtpar, Lahijan, Langarud, Masuleh, Manjil, Rudbar, Rudsar, Shaft, Siahkal, and Sowme'eh Sara.

Stone artifacts and animal fossils were discovered by a group of Iranian archaeologists that dates back to the late Chibanian.

[16] It seems that the Gelae, or Gilites, entered the region south of the Caspian coast and west of the Amardos River (now called the Sefid-Rud) in the second or first century BCE, Pliny identifies them with the Cadusii who were living there previously.

Previously, the people of the province had a prominent position during the Sassanid dynasty through the 7th century, so that their political power extended to Mesopotamia.

In fact, it was the Deylamites under the Buyid king Mu'izz al-Dawla who finally shifted the balance of power by conquering Baghdad in 945.

Muslim chronicles of Varangian (Rus', pre-Russian Norsemen) invasions of the littoral Caspian region in the 9th century record Deylamites as non-Muslim.

[21] Initially, the Rus' appeared in Serkland in the 9th century traveling as merchants along the Volga trade route, selling furs, honey, and slaves.

The Rus' undertook the first large-scale expedition in 913; having arrived on 500 ships, they pillaged the westernmost parts of Gorgan as well as Gilan and Mazandaran, taking slaves and goods.

The Turkish invasions of the 10th and 11th centuries CE, which saw the rise of Ghaznavid and Seljuk dynasties, put an end to Deylamite states in Iran.

Before the introduction of silk production (date unknown but a pillar of the economy by the 15th century AD), Gilan was a poor province.

It seems that the city of Qazvin was initially a fortress-town against marauding bands of Deylamites, another sign that the economy of the province did not produce enough on its own to support its population.

In the mid-19th century, a fatal epidemic among the silk worms paralyzed Gilan's economy, causing widespread economic distress.

After World War I, Gilan came to be ruled independently of the central government of Tehran and concern arose that the province might permanently separate.

Sepahdar-e Tonekaboni (Rashti) was a prominent figure in the early years of the revolution and was instrumental in defeating Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar.

In the late 1910s, many Gilanis gathered under the leadership of Mirza Kuchik Khan, who became the most prominent revolutionary leader in northern Iran in this period.

However, the revolution did not progress the way the constitutionalists had strived for, and Iran came to face much internal unrest and foreign intervention, particularly from the British and Russian empires.

During and several years after the Bolshevik Revolution, the region saw another massive influx of Russian settlers (the so-called White émigrées).

The Jangalis continued to struggle against the central government until their final defeat in September 1921 when control of Gilan returned to Tehran.

Gilaks form the majority of the population, while Azerbaijanis, Kurds, Talysh and Persians are significant minorities in the province.

The population history and structural changes of Gilan province's administrative divisions over three consecutive censuses are shown in the following table.

Rainfall is heaviest between September and December because the onshore winds from the Siberian High are strongest, but it occurs throughout the year though least abundantly from April to August.

Humidity is very high because of the marshy character of the coastal plains and can reach 90 percent in summer for wet bulb temperatures of over 26 °C (79 °F).

Due to successive cultivation and selection of rice by farmers, several cultivars including Gerdeh, Hashemi, Hasani, and Gharib have been bred.