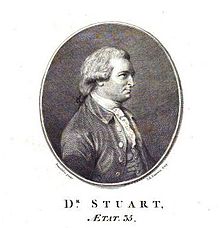

Gilbert Stuart (writer)

In the end, an article by Stuart and Alexander Gillies, written over the protests of William Smellie, attacked Lord Monboddo's Origin and Progress of Language over several numbers.

In 1778 Stuart was an unsuccessful candidate for the professorship of public law at the University of Edinburgh, and he believed that Robertson was responsible for his failure.

[1] Stuart would spend whole nights drinking in company at the Peacock in Gray's Inn Lane, London.

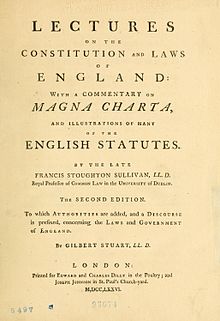

[1] Stuart's major work, A View of Society in Europe, was published in 1778, and reprinted in 1782, 1783, 1792, and 1813, and a French translation by Antoine-Marie-Henri Boulard, came out in Paris in 1789, in two volumes.

Letters from William Blackstone and Alexander Garden were added to the posthumous edition of 1792 by Stuart's father.

[1] As a contributor to medievalism he is considered a pioneer, sharing with Thomas Hinton Burley Oldfield the conception of early Anglo-Saxon society as harbouring democratic habits.

Stuart trailed his coat for Robertson, whom he openly challenged to reply to his defence of Queen Mary.

[5] Stuart did have a public ally in David Erskine, 11th Earl of Buchan, who made a point of praising him in a speech at the founding of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, in 1780.

Another historian on the Whig side, whom Stuart found tolerable, was Sir John Dalrymple of Cousland.