Gilding

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone.

This may mean that all of the inside, and none of the outside, of a chalice or similar vessel is gilded, or that patterns or images are made up by using a combination of gilt and ungilted areas.

Owing to the comparative thickness of the gold leaf used in ancient gilding, the traces of it that remain are remarkably brilliant and solid.

[5] It was known to Pliny (33,20,64–5), Vitruvius (8,8,4) and in the early medieval period to Theophilus (De Diversis Artibus Book III).

[citation needed] The ancient Chinese also developed the gilding of porcelain, which was later taken up by the French and other European potters.

The Ram in a Thicket (2600–2400 BC) from Ur describes this technique used on wood, with a thin layer of bitumen underneath to help adhesion.

Once the coating of gesso had been applied, allowed to dry, and smoothed, it was re-wet with a sizing made of rabbit-skin glue and water ("water gilding", which allows the surface to be subsequently burnished to a mirror-like finish) or boiled linseed oil mixed with litharge ("oil gilding", which does not) and the gold leaf was layered on using a gilder's tip and left to dry before being burnished with a piece of polished agate.

Those gilding on canvas and parchment also sometimes employed stiffly-beaten egg whites ("glair"), gum, and/or Armenian bole as sizing, though egg whites and gum both become brittle over time, causing the gold leaf to crack and detach, and so honey was sometimes added to make them more flexible.

These techniques remained the only alternatives for materials like wood, leather, the vellum pages of illuminated manuscripts, and gilt-edged stock.

[3] Wet gilding is effected by means of a dilute solution of gold(III) chloride in aqua regia with twice its quantity of ether.

The ether will be found to have taken up all the gold from the acid, and may be used for gilding iron or steel, for which purpose the metal is polished with fine emery and spirits of wine.

[3] When the metal to be gilded is wrought or chased, the application of mercury before the amalgam is applied allows for it to be more easily spread.

Gilding wax is composed of beeswax mixed with some of the following substances: red ochre, verdigris, copper scales, alum, vitriol, and borax.

The gilt surface is then covered over with potassium nitrate, alum or other salts, ground together, and mixed into a paste with water or weak ammonia.

[10] By this method, the color of the gilding is further improved and brought nearer to that of gold, probably by removing any particles of copper that may have been on the gilt surface.

[11] This method of gilding metallic objects was formerly widespread, but fell into disuse as the dangers of mercury toxicity became known.

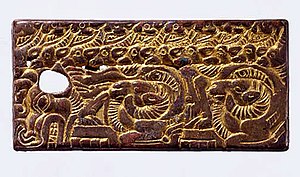

In depletion gilding, a subtractive process discovered in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, articles are fabricated by various techniques from an alloy of copper and gold, named tumbaga by the Spaniards.

The gilding of decorative ceramics has been undertaken for centuries, with the permanence and brightness of gold appealing to designers.

The most important factors affecting coating quality are the composition of applied gold, the state of the surface before application, the thickness of the layer and the firing conditions.

The jelly will cause the metal to adhere very gently to the hairs and allow the piece to be floated from the paper surface on which had previously been stored.