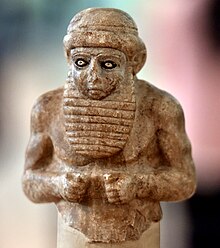

Gilgamesh and Aga

[2] The poem records the Kishite siege of Uruk after lord Gilgamesh refused to submit to them, ending in Aga's defeat and consequently the fall of Kish's hegemony.

[4] The location of the battle is described as having occurred outside the walls of Uruk, situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River.

Some scholars regarded the tale as a reflection of the relations between Sumerians and Semitics, a potentially important but as yet obscure issue of early Mesopotamian history.

It was first published in 1935 by T. Fish, in the Bulletin of the John Rylands Library XIX, and first transliterated and translated by Samuel Noah Kramer in 1949.

[4] Parallelism, common in Sumerian Literature, is present; such as the message and response of Aga and the able-bodied men respectively, or Birhurtura's dialogue with Gilgamesh's actions on the battle.

There are no mythological implications or gods, as seen in the other Gilgamesh stories, and the material of the plot seems to be taken from the reality of foreign relations between Sumerian cities.

Enkidu charges against the enemy troops while Gilgamesh stands on the wall, and this portrayal as a current human being, unlike his other tales, creates the impression of authenticity.

[4] According to the Sumerian King List (ETCSL 2.1.1), Kish had hegemony over Sumer, where Aga reigned 625 years, succeeding his father Enmebaragesi to the throne, finally defeated by Uruk.

[20] There is some scant evidence to suggest that, like the later Ur III kings, the rulers of ED Kish sought to ingratiate themselves to the authorities in Nippur, possibly to legitimize a claim for leadership over the land of Sumer or at least part of it.

A vivid example of the importance of canals is found in the Stele of Vultures, erected by Eannatum of Lagash to commemorate a success in the long conflict between his city and its neighbor Umma.

After describing the hostilities and his victory, Eannatum relates in detail the oath taken by the king of Umma, which concerns the irrigation system.

Pre-Sargonic Lagash texts show that mass killings of war prisoners and recruiting foreign forces to strengthen the city were not unknown.

Aga's demand was found in a proverb collection, making the answer of the able-bodied men functionally parallel, since both are made from the literally same model.

While assemblies existed,[25] there's no record of their composition or function until the Early Dynastic Period III.a According to Old Babylonian texts, the king had full political authority.

Jacobsen, who used mythological texts for extracting historical information, used the Enuma Elish which relates how the assembly of gods decided to face Tiamat.

[27] Another theory based on the pre-Sargonic Lagash texts, suggested that the City fathers represented the estate-owning nobility while the able-bodied men were the members of the community, who cultivated small family plots, and both organizations shared power with the king on issues of temples, irrigation, and construction.

[4] Kramer theorized the existence of a bicameral political structure,[29] however the poem, rather than being historically accurate, creates an antithetical parallelb taken for reality, elders and the assembly were two separated political entities (contradicting the poem's story) while the able-bodied men were an element of the city's population working for the military.

And when finally Gilgamesh leans on the wall, his appearance does not affect Aga's army but the people of Uruk, the young (able-bodied men) and the old ("City fathers").

When Gilgamesh steps on the wall, Aga is not physically overwhelmed by his sight, but his army collapses the moment Birhurtura declares he is his king.

[31] According to Jacobsen, Gilgamesh was appointed in Uruk as a vassal by his king Aga, then, moved by an heroic pride, instigated a rebellion.