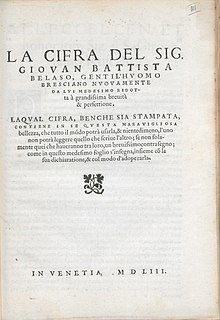

Giovan Battista Bellaso

His father was Piervincenzo, a patrician of Brescia, owner since the 15th century of a house in town and a suburban estate in Capriano, in a neighborhood called Fenili Belasi (Bellaso's barns), including the Holy Trinity chapel.

Versed in research, able in mathematics, Bellaso dealt with secret writing at a time when this art enjoyed great admiration in all the Italian courts, mainly in the Roman Curia.

In this golden period of the history of cryptography, he was just one of many secretaries who, out of intellectual passion or for real necessity, experimented with new systems during their daily activities.

Polyalphabetic substitution with mixed alphabets, frequently changed without a period, is attributed to Leon Battista Alberti, who described it in his famous treatise De cifris of 1466.

This crucial invention has a limit in that it obliges the encipherer to indicate, within the body of the cryptogram, the index letters determining the choice of the next alphabet.

It was Giovan Battista Bellaso who first suggested identifying the alphabets by means of an agreed-upon countersign or keyword off-line.

Arma uirumque cano troie qui primus ab oris Long countersign: Qui confidunt in Domino etc... Enciphering: QQQQ UUUU IIII ... Countersign Giul ioCe sare ... Plaintext NQHP MSGN XDYT ... Ciphertext Bellaso's third book was printed in 1564 and dedicated to Alessandro Farnese.

Bellaso bitterly writes in 1564, that somebody in that same year was ‘‘sporting his clothes and divesting him of his labors and honors.’’ This is a clear allusion to Della Porta, who printed the reciprocal table in 1563 without mentioning the true inventor.

In the introduction of the book he lists thirteen qualities distinguishing his ciphers from other systems, and in a final section he claims priority for these four inventions: Bellaso challenged[1] his detractors to solve some cryptograms encrypted according to his guidelines.

He also furnished the following clue to help the solution of one of them: ‘‘The cryptogram contains the explanation why two balls, one in iron and one in wood, dropped from a high place will fall on the ground at the same time.’’ This is a clear statement of the law of the free-falling bodies forty years before Galileo.