Girih tiles

They have been used since about the year 1200 and their arrangements found significant improvement starting with the Darb-i Imam shrine in Isfahan in Iran built in 1453.

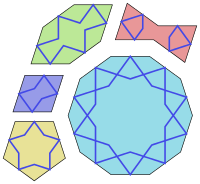

The five shapes of the tiles, and their Persian names, are:[1] All sides of these figures have the same length, and all their angles are multiples of 36° (π/5 radians).

The tiles are used to form girih patterns, from the Persian word گره, meaning "knot".

[4][5] This finding was supported both by analysis of patterns on surviving structures, and by examination of 15th-century Persian scrolls.

Found in the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, the administrative center of the Ottoman Empire, and believed to date from the late 15th century, the scroll shows a succession of two- and three-dimensional geometric patterns.

There is no text, but there is a grid pattern and color-coding used to highlight symmetries and distinguish three-dimensional projections.

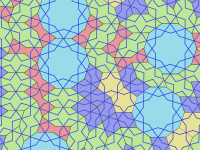

In this way, craftsmen could make highly complex designs without resorting to mathematics and without necessarily understanding their underlying principles.

[6] This use of repeating patterns created from a limited number of geometric shapes available to craftsmen of the day is similar to the practice of contemporary European Gothic artisans.

Designers of both styles were concerned with using their inventories of geometrical shapes to create the maximum diversity of forms.

The following figure illustrates a step-by-step compass-straightedge visual solution to the problem by the author.

The specific types of embellishments utilized in orosi typically linked the windows to the patron's social and political eminence.