Origin of language

The shortage of direct, empirical evidence has caused many scholars to regard the entire topic as unsuitable for serious study; in 1866, the Linguistic Society of Paris banned any existing or future debates on the subject, a prohibition which remained influential across much of the Western world until the late twentieth century.

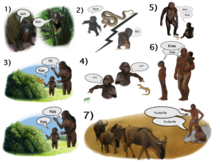

[14] Transcending the continuity-versus-discontinuity divide, some scholars view the emergence of language as the consequence of some kind of social transformation[15] that, by generating unprecedented levels of public trust, liberated a genetic potential for linguistic creativity that had previously lain dormant.

A very specific social structure – one capable of upholding unusually high levels of public accountability and trust – must have evolved before or concurrently with language to make reliance on "cheap signals" (e.g. words) an evolutionarily stable strategy.

Since the emergence of language lies so far back in human prehistory, the relevant developments have left no direct historical traces, and comparable processes cannot be observed today.

Few dispute that Australopithecus probably lacked vocal communication significantly more sophisticated than that of great apes in general,[29] but scholarly opinions vary as to the developments since the appearance of Homo some 2.5 million years ago.

[30] Estimates of this kind are not universally accepted, but jointly considering genetic, archaeological, palaeontological, and much other evidence indicates that language likely emerged somewhere in sub-Saharan Africa during the Middle Stone Age, roughly contemporaneous with the speciation of Homo sapiens.

[31] I cannot doubt that language owes its origin to the imitation and modification, aided by signs and gestures, of various natural sounds, the voices of other animals, and man's own instinctive cries.

If language evolved initially for communication between mothers and their own biological offspring, extending later to include adult relatives as well, the interests of speakers and listeners would have tended to coincide.

Fitch argues that shared genetic interests would have led to sufficient trust and cooperation for intrinsically unreliable signals—words—to become accepted as trustworthy and so begin evolving for the first time.

Dunbar argues that as humans began living in increasingly larger social groups, the task of manually grooming all one's friends and acquaintances became so time-consuming as to be unaffordable.

[citation needed] Critics of the speech/ritual co-evolution idea theory include Noam Chomsky, who terms it the "non-existence" hypothesis—a denial of the very existence of language as an object of study for natural science.

Researchers used functional transcranial Doppler ultrasonography (fTDC) and had participants perform activities related to the creation of tools using the same methods during the Lower Paleolithic as well as a task designed specifically for word generation.

Citing evolutionary geneticist Svante Pääbo, they concur that a substantial difference must have occurred to differentiate Homo sapiens from Neanderthals to "prompt the relentless spread of our species, who had never crossed open water, up and out of Africa and then on across the entire planet in just a few tens of thousands of years. ...

[87] Another criticism has questioned the logic of the argument for single mutation and puts forward that from the formal simplicity of Merge, the capacity Berwick and Chomsky deem the core property of human language that emerged suddenly, one cannot derive the (number of) evolutionary steps that led to it.

[90] Then, the second phase was a rapid Chomskian single step, consisting of three distinct events that happened in quick succession around 70,000 years ago and allowed the shift from non-recursive to recursive language in early hominins.

This suggests that the mutation that caused PFC delay and the development of recursive language and PFS occurred simultaneously, which lines up with evidence of a genetic bottleneck around 70,000 years ago.

[109] However, Michael Corballis has pointed out that it is supposed that primate vocal communication (such as alarm calls) cannot be controlled consciously, unlike hand movement, and thus it is not credible as precursor to human language; primate vocalization is rather homologous to and continued in involuntary reflexes (connected with basic human emotions) such as screams or laughter (the fact that these can be faked does not disprove the fact that genuine involuntary responses to fear or surprise exist).

[121] According to Dean Falk's "putting-down-the-baby" theory, vocal interactions between early hominid mothers and infants began a sequence of events that led, eventually, to human ancestors' earliest words.

In order to convey abstract ideas, the first recourse of speakers is to fall back on immediately recognizable concrete imagery, very often deploying metaphors rooted in shared bodily experience.

Given the highly indeterminate way that mammalian brains develop—they basically construct themselves "bottom up", with one set of neuronal interactions preparing for the next round of interactions—degraded pathways would tend to seek out and find new opportunities for synaptic hookups.

[161] Some captive primates (notably bonobos and chimpanzees), having learned to use rudimentary signing to communicate with their human trainers, proved able to respond correctly to complex questions and requests.

Bird-song, singing nonhuman apes, and the songs of whales all display phonological syntax, combining units of sound into larger structures apparently devoid of enhanced or novel meaning.

[29] One notable finding is that nonhuman primates, including the other great apes, produce calls that are graded, as opposed to categorically differentiated, with listeners striving to evaluate subtle gradations in signallers' emotional and bodily states.

[184] Opposing research previously suggested that Neanderthals were physically incapable of creating the full range of vocals seen in modern humans due to the differences in larynx placement.

Establishing distinct larynx positions through fossil remains of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals would support this theory; however, modern research has revealed that the hyoid bone was indistinguishable in the two populations.

[203] These researchers claim that this finding implies that "Neanderthals evolved the auditory capacities to support a vocal communication system as efficient as modern human speech.

[26] According to the recent African origins hypothesis, from around 60,000 – 50,000 years ago[206] a group of humans left Africa and began migrating to occupy the rest of the world, carrying language and symbolic culture with them.

[213] Uniquely in the human case, simple contact between the epiglottis and velum is no longer possible, disrupting the normal mammalian separation of the respiratory and digestive tracts during swallowing.

[223] In the Old Testament, the Book of Genesis (chapter 11) says that God prevented the Tower of Babel from being completed through a miracle that made its construction workers start speaking different languages.

[citation needed] However, scholarly interest in the question of the origin of language has only gradually been rekindled[colloquialism] from the 1950s on (and then controversially) with ideas such as universal grammar, mass comparison and glottochronology.