Dressage

Dressage (/ˈdrɛsɑːʒ/ or /drɪˈsɑːʒ/; French: [dʁɛsaʒ], most commonly translated as "training") is a form of horse riding performed in exhibition and competition, as well as an art sometimes pursued solely for the sake of mastery.

Modern dressage has evolved as an important equestrian pursuit since the Renaissance when Federico Grisone's "The Rules of Riding" was published in 1550, one of the first notable European treatises on equitation since Xenophon's On Horsemanship.

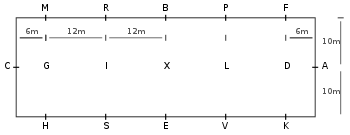

In modern dressage competition, successful training at the various levels is demonstrated through the performance of "tests", prescribed series of movements ridden within a standard arena.

In classical dressage training and performances that involve the "airs above the ground" (described below), the "baroque" breeds of horses are popular and purposely bred for these specialties.

The traditions of the masters who originated Dressage are kept alive by the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, Austria, Escola Portuguesa de Arte Equestre in Lisbon, Portugal, and the Cadre Noir in Saumur, France.

At the upper levels, tests for international competitions, including the Olympics, are issued under the auspices of the FEI.

[4] Movements that are given a coefficient are generally considered to be particularly important to the horse's progression in training, and should be competently executed prior to moving up to the next level of competition.

In addition to this, the scribe should check the identity of each competitor, and ensure that the test papers are complete and signed before handing them to the scorers.

"[6] Scribing or pencilling is also an integral part of a judge's training as they look to become accredited or upgrade to a higher level.

The team competition serves as the first individual qualifier, in that the top 25 horse/rider combinations from the Grand Prix test move on to the next round.

Competitive dressage training in the U.S. is based on a progression of six steps developed by the German National Equestrian Foundation.

Rhythm, gait, tempo, and regularity should be the same on straight and bending lines, through lateral work, and through transitions.

Once a rider can obtain pure gaits, or can avoid irregularity, the combination may be fit to do a more difficult exercise.

Even in the very difficult piaffe there is still regularity: the horse "trots on the spot" in place, raising the front and hind legs in rhythm.

The pushing power (thrust) of the horse is called impulsion, and is the fourth level of the training pyramid.

Impulsion is created by storing the energy of engagement (the forward reaching of the hind legs under the body).

Impulsion not only encourages correct muscle and joint use, but also engages the mind of the horse, focusing it on the rider and, particularly at the walk and trot, allowing for relaxation and dissipation of nervous energy.

In essence, collection is the horse's ability to move its centre of gravity to the rear while lifting the freespan of its back to better round under the rider.

However, while agility was necessary on the battlefield, most of the airs as performed today would have actually exposed horses' vulnerable underbellies to the weapons of foot soldiers.

[11] It is therefore more likely that the airs were exercises to develop the agility, responsiveness and physiology of the military horse and rider, rather than to be employed in combat.

The earliest practitioner who wrote treatises that survive today that describe sympathetic and systematic training of the horse was the Greek general Xenophon (427–355 BC).

Beginning in the Renaissance a number of early modern trainers began to write on the topic of horse training, each expanding upon the work of their predecessors, including Federico Grisone (mid-16th century), Antoine de Pluvinel (1555–1620), William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle (1592–1676), François Robichon de La Guérinière (1688–1751), François Baucher (1796–1873), and Gustav Steinbrecht (1808–1885).

The 20th century saw an increase in writing and teaching about Dressage training and techniques as the discipline became an international sport with the influence of Olympic Equestrian competition.

Traditionally, the snaffle is used to open and lift the poll angle, while the curb is used to bring the nose of the horse towards the vertical.

The tail should be "banged", or cut straight across[citation needed] (usually above the fetlocks but below the hocks when held at the point where the horse naturally carries it).

Some riders believe that foam should not be cleaned off the horse's mouth before entering the arena due to it being a sign of submission.

Spurs are required at the upper levels, and riders must maintain a steady lower leg for proper use.

At the upper levels, a top hat that matches the rider's coat is traditionally worn, though use of helmets is legal and increasing in popularity.

The FEI has banned hyperflexion of horse’s neck, the Rollkur technique, but a July 2014 article in the Guardian notes that it was still in use.

[25][26] The ban on star UK rider Charlotte Dujardin before the Paris Olympics in July 2024 raised the public awareness on the welfare of dressage horses.