Grant's Canal

During the American Civil War, the Union Navy attempted to capture the Confederate-held city of Vicksburg in 1862, but were unable to do so with army support.

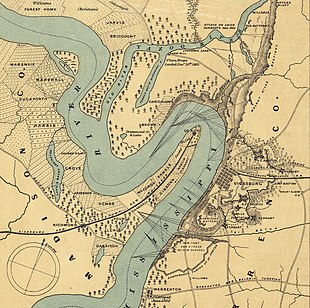

Union Brigadier-General Thomas Williams was sent to De Soto Point with 3,200 men to dig a canal capable of bypassing the strong defenses around Vicksburg.

Grant attempted to resolve some of the issues inherent to the concept by moving the upstream entrance to a spot with a stronger current, but the heavy rains and flooding that broke a dam prevented the project from succeeding.

Work was abandoned in March, and Grant eventually used other methods to capture Vicksburg, whose Confederate garrison surrendered on July 4, 1863.

A major part of this plan was controlling the Mississippi River, to cut the Confederacy in two and provide a supply outlet for northern goods to reach foreign markets.

[1] In early 1862, the Union Army defeated Confederate forces in several significant battles, including Shiloh, First Corinth, Fort Donelson, and Island Number Ten.

On May 20, the first Union shot towards Vicksburg was fired by USS Oneida, and more bombardments followed on May 26 and 28 before Farragut decided to fall back to New Orleans, a move that was politically unpopular.

[3] The decision to withdraw was the result of falling river levels threatening to strand the Union ships, a shortage of coal, and Farragut being ill.[6] Another attempt on the city was made in June.

Williams's infantrymen, Farragut's fleet, and a group of ships armed with mortars commanded by Commodore David Dixon Porter left the city of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on June 20.

[7] On June 26, Porter and Farragut's ships attempted to bombard the Confederate artillery batteries defending the city, but were unable to do so.

[8] Two days later, Farragut ordered most of his ships (but not Porter's) to pass in front of the city's defenses to meet a fleet of Union ironclads that had traveled down the river from Memphis, Tennessee.

[14][16] While the path of the canal could conceivably have been as short as 0.75 miles (1 km), the longer route was chosen to stay further from Vicksburg's defenses.

[17] If the plan worked as intended, the Mississippi would cut through the canal ditch, allowing Union ships to traverse the river without being fired on by the defenders of Vicksburg.

[14] As the conditions deteriorated further, Williams decided that the canal was no longer feasible and ordered his men from De Soto Point, ending work on July 24.

[24][25] In addition to the problems at the canal site, the Confederates were showing signs of activity in the Baton Rouge area and near the Red River.

[27] When the Confederate States Army later examined the area where the canal construction had taken place, they found 600 graves and 500 abandoned African Americans,[25] most of whom were ill.

[32] A direct attack on Vicksburg was impractical; the strength of the Confederate defenses had been improved since Farragut's campaign the previous year, the terrain north of the city in the Mississippi Delta was impassable to an army, and a withdrawal to Memphis to make a second overland attempt would be publicly viewed as a defeat and would be politically disastrous.

The steamboat Catahoula was sent to the area in January 1863 by the Union, under the command of a Lieutenant Wilson, to scout the remains of the canal cut.

Both the captain of the vessel and a newspaperman on board reported that while there was water standing in the canal, it was stagnant and that the cut needed significant work before large ships such as Union Navy ironclads could pass through it.

[34] Union Colonel Josiah W. Bissell, who had prior engineering experience, surveyed the canal on January 10 and noted that it was still in similar shape as to how Williams left it.

[43] Major-General Carter L. Stevenson, the immediate Confederate commander of the Vicksburg defenses, originally interpreted the Union movement to the canal site as preparatory to cross the river at Warrenton, Mississippi.

[45] Water depth was increased to 5 feet (2 m), and in hopes of creating greater erosion in the canal, soldiers were ordered to dig pits along its sides.

[50] Rains hampered the project by exposing poorly buried graves from the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou and turning the soil to a consistency Sherman described as "wet, almost water".

This process was completed by February 9, although it was noted that evidence of current-based erosion was finally sighted shortly before the canal was closed off.

[61] The flooding had caused the cut to begin to fill with sediment, and the two dredging boats, Hercules and Sampson, were sent to try to clear the channel, but they came under Confederate artillery fire.

[40] Grant viewed the canal construction as a good way to prevent idleness among his soldiers, but eventually conceived another way to get troops past Vicksburg.

Union troops cut levees on March 4 and 17, but the project encountered difficulties with trees blocking the path, and Grant had the attention given there redirected elsewhere before a needed sawing machine arrived.

After Vicksburg surrendered, the Confederate garrison of Port Hudson, Louisiana, followed suit, giving the Union full control of the Mississippi River.

Some outside observers did view Grant's Canal as the best option for taking the city, and it received press attention in the Union, Confederacy, and Europe.

[77] Likewise, the historian Shelby Foote included the canal as one of seven different failed attempts made before Grant successfully took Vicksburg.