Steele's Bayou expedition

The Steele's Bayou expedition was a joint operation of Major General Ulysses S. Grant's Army of the Tennessee and Rear Admiral David D. Porter's Mississippi River Squadron, conducted as a part of the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War.

Exploiting this, the Rebels further impeded progress by felling trees across the stream, and brought the Union force to a halt within 1.5 miles (2.4 km) of the Rolling Fork.

With his vessels effectively trapped, Porter sent an urgent appeal for help to the Army, and then issued orders to his captains to prepare to destroy their ships rather than let them fall into enemy hands.

They easily drove off the Confederate patrols that were blocking the retreat, so Porter and his vessels were able to move back into Steele's Bayou.

To avoid the lethargy in command that had hampered the Yazoo Pass operation, Porter himself went with the gunboats, and the Army was under the personal direction of Major General William T.

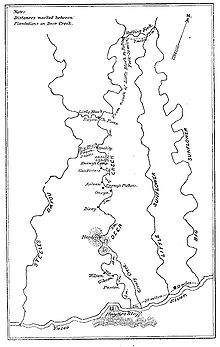

The last met the Yazoo River a short distance upstream from the bluffs where a major Union attack had been repulsed in late 1862.

[6] Porter had to rely on imperfect maps and the advice of local citizens who did not understand the difficulties of moving heavy warships in a narrow channel with numerous bends.

[7] He was also unaware of the impedance to mobility imposed by the overhanging trees that grew down to the water's edge and by the submerged vegetation that seized the hulls of his vessels.

The naval contingent was spearheaded by five Pook turtles, USS Louisville, Cincinnati, Carondelet, Mound City, and Pittsburg.

He saw that the overgrowth would be a serious obstacle; while the armored gunboats could push aside the limbs in their path, the smokestacks and upper works of the flimsier transports would be severely battered.

Major General Carter L. Stevenson, who commanded the Confederate district, was aware of the growing threat to Vicksburg almost as soon as the expedition cleared Steele's Bayou.

The earliest Rebel troops to arrive were those of Lee, a battalion of infantry, six field pieces of artillery, and 40 to 50 cavalry, all led by Lieutenant Colonel Samuel W. Ferguson.

They occupied a small Indian mound that dominated the field and were for a time able to drive the enemy away, and the gunboats managed to crawl forward to within 0.5 miles (0.80 km) of the Rolling Fork.

There they skirmished with Ferguson's force until the light failed, and the Union shore party retired to the protection of the armor of their vessels.

About the time the ships began to move, however, a plantation slave brought word that some of the Confederate troops had slipped around the flotilla and were felling trees in their rear.

The report was confirmed by (Union) Colonel Giles Smith of the 8th Missouri Infantry, who had come up Deer Creek and had counted more than forty large trees lying across the stream.

Porter unhesitatingly accepted Grant's position, and he immediately began to advise the general how best to incorporate the Navy into his plans.

In the view of his biographer Chester Hearn, the failure of the Steele's Bayou expedition at an earlier time in his career would likely have resulted in recriminations against his subordinates, superiors, and colleagues.