Gravity of Earth

This means that, ignoring the effects of air resistance, the speed of an object falling freely will increase by about 9.8 metres per second (32 ft/s) every second.

[4] This quantity is denoted variously as gn, ge (though this sometimes means the normal gravity at the equator, 9.7803267715 m/s2 (32.087686258 ft/s2)),[5] g0, or simply g (which is also used for the variable local value).

Gravity does not normally include the gravitational pull of the Moon and Sun, which are accounted for in terms of tidal effects.

The Earth is rotating and is also not spherically symmetric; rather, it is slightly flatter at the poles while bulging at the Equator: an oblate spheroid.

In 1901, the third General Conference on Weights and Measures defined a standard gravitational acceleration for the surface of the Earth: gn = 9.80665 m/s2.

It was based on measurements at the Pavillon de Breteuil near Paris in 1888, with a theoretical correction applied in order to convert to a latitude of 45° at sea level.

This counteracts the Earth's gravity to a small degree – up to a maximum of 0.3% at the Equator – and reduces the apparent downward acceleration of falling objects.

The force due to gravitational attraction between two masses (a piece of the Earth and the object being weighed) varies inversely with the square of the distance between them.

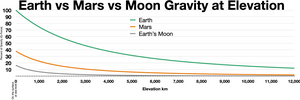

All other things being equal, an increase in altitude from sea level to 9,000 metres (30,000 ft) causes a weight decrease of about 0.29%.

(An additional factor affecting apparent weight is the decrease in air density at altitude, which lessens an object's buoyancy.

[11] This would increase a person's apparent weight at an altitude of 9,000 metres by about 0.08%) It is a common misconception that astronauts in orbit are weightless because they have flown high enough to escape the Earth's gravity.

In fact, at an altitude of 400 kilometres (250 mi), equivalent to a typical orbit of the ISS, gravity is still nearly 90% as strong as at the Earth's surface.

The gravity depends only on the mass inside the sphere of radius r. All the contributions from outside cancel out as a consequence of the inverse-square law of gravitation.

The fluctuations are measured with highly sensitive gravimeters, the effect of topography and other known factors is subtracted, and from the resulting data conclusions are drawn.

Denser rocks (often containing mineral ores) cause higher than normal local gravitational fields on the Earth's surface.

There is a strong correlation between the gravity derivation map of earth from NASA GRACE with positions of recent volcanic activity, ridge spreading and volcanos: these regions have a stronger gravitation than theoretical predictions.

Additionally, Newton's second law, F = ma, where m is mass and a is acceleration, here tells us that Comparing the two formulas it is seen that: So, to find the acceleration due to gravity at sea level, substitute the values of the gravitational constant, G, the Earth's mass (in kilograms), m1, and the Earth's radius (in metres), r, to obtain the value of g:[20] This formula only works because of the mathematical fact that the gravity of a uniform spherical body, as measured on or above its surface, is the same as if all its mass were concentrated at a point at its centre.

Currently, the static and time-variable Earth's gravity field parameters are determined using modern satellite missions, such as GOCE, CHAMP, Swarm, GRACE and GRACE-FO.

[21][22] The lowest-degree parameters, including the Earth's oblateness and geocenter motion are best determined from satellite laser ranging.