Gray molasses

Gray molasses is a method of sub-Doppler laser cooling of atoms.

It employs principles from Sisyphus cooling in conjunction with a so-called "dark" state whose transition to the excited state is not addressed by the resonant lasers.

Ultracold atomic physics experiments on atomic species with poorly-resolved hyperfine structure, like isotopes of lithium[1] and potassium,[2] often utilize gray molasses instead of Sisyphus cooling as a secondary cooling stage after the ubiquitous magneto-optical trap (MOT) to achieve temperatures below the Doppler limit.

Unlike a MOT, which combines a molasses force with a confining force, a gray molasses can only slow but not trap atoms; hence, its efficacy as a cooling mechanism lasts only milliseconds before further cooling and trapping stages must be employed.

Like Sisyphus cooling, the cooling mechanism of gray molasses relies on a two-photon Raman-type transition between two hyperfine-split ground states mediated by an excited state.

As neither are eigenstates of the kinetic energy operator, the dark state also evolves into the bright state with frequency proportional to the atom's external momentum.

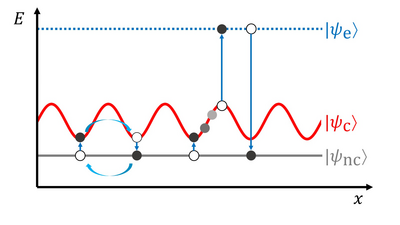

Gradients in the polarization of the molasses beam create a sinusoidal potential energy landscape for the bright state in which atoms lose kinetic energy by traveling "uphill" to potential energy maxima that coincide with circular polarizations capable of executing electric dipole transitions to the excited state.

Alternately, the pair of bright and dark ground states can be generated by electromagnetically-induced transparency (EIT).

[3] [4] The net effect of many cycles from bright to excited to dark states is to subject atoms to Sisyphus-like cooling in the bright state and select the coldest atoms to enter the dark state and escape the cycle.

The latter process constitutes velocity-selective coherent population trapping (VSCPT).

[5] The combination of bright and dark states thus inspires the name "gray molasses."

In 1988, The NIST group in Washington led by William Phillips first measured temperatures below the Doppler limit in sodium atoms in an optical molasses, prompting the search for the theoretical underpinnings of sub-Doppler cooling.

[6] The next year, Jean Dalibard and Claude Cohen-Tannoudji identified the cause as the multi-photon process of Sisyphus cooling,[7] and Steven Chu's group likewise modeled sub-Doppler cooling as fundamentally an optical pumping scheme.

[8] As a result of their efforts, Phillips, Cohen-Tannoudji, and Chu jointly won the 1997 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Hänsch, et al., first outlined the theoretical formulation of gray molasses in 1994,[9] and a four-beam experimental realization in cesium was achieved by G. Grynberg the next year.

atomic ground state manifold experience equal and opposite AC Stark shifts from the near-resonant counter-propagating beams.

coincide with pure circular polarization, which optically pumps atoms to the other

Over time, the atoms expend their kinetic energy traversing the potential energy landscape and transferring the potential energy difference between the crests and troughs of the AC-Stark-shifted ground state levels to emitted photons.

[7] In contrast, gray molasses only has one sinusoidally light-shifted ground state; optical pumping at the peaks of this potential energy landscape takes atoms to the dark state, which can selectively evolve to the bright state and re-enter the cycle with sufficient momentum.

Sisyphus cooling is difficult to implement when the excited state manifold is poorly-resolved (i.e. whose hyperfine spacing is comparable to or less than the constituent linewidths); in these atomic species, the Raman-type gray molasses is preferable.

In the presence of counter-propagating beams of opposite polarization, the internal states experience the atom-light interaction Hamiltonian where

Using the definition of the translation operator in momentum space, the effect of

undergo Sisyphus-like cooling, identifying the former as the bright state.

are not eigenstates of the momentum operator, and thus motionally couple to one another via the kinetic energy term of the unperturbed Hamiltonian: As a result of this coupling, the dark state evolves into the bright state with frequency proportional to the momentum, effectively selecting hotter atoms to re-enter the Sisyphus cooling cycle.

Over time, atoms cool until they lack the momentum to traverse the sinusoidal light shift of the bright state and instead populate the dark state.

In experimental settings, this condition is realized when the detunings of the cycling and repumper frequencies in respect to the

[note 1] Unlike most Doppler cooling techniques, light in the gray molasses must be blue-detuned from its resonant transition; the resulting Doppler heating is offset by polarization-gradient cooling.

means that the AC Stark shifts of the three levels are the same sign at any given position.

Selecting the potential energy maxima as the sites of optical pumping to the dark state requires the overall light to be blue-detuned; in doing so, the atoms in the bright state traverse the maximum potential energy difference and thus dissipate the most kinetic energy.

A full quantitative explanation of the molasses force with respect to detuning can be found in Hänsch's paper.