Isotope

[1] The term isotope is derived from the Greek roots isos (ἴσος "equal") and topos (τόπος "place"), meaning "the same place"; thus, the meaning behind the name is that different isotopes of a single element occupy the same position on the periodic table.

[2] It was coined by Scottish doctor and writer Margaret Todd in a 1913 suggestion to the British chemist Frederick Soddy, who popularized the term.

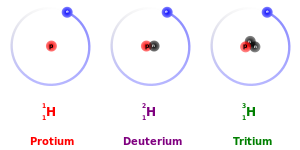

Even for the lightest elements, whose ratio of neutron number to atomic number varies the most between isotopes, it usually has only a small effect although it matters in some circumstances (for hydrogen, the lightest element, the isotope effect is large enough to affect biology strongly).

The existence of isotopes was first suggested in 1913 by the radiochemist Frederick Soddy, based on studies of radioactive decay chains that indicated about 40 different species referred to as radioelements (i.e. radioactive elements) between uranium and lead, although the periodic table only allowed for 11 elements between lead and uranium inclusive.

[18][19][20][21] Soddy recognized that emission of an alpha particle followed by two beta particles led to the formation of an element chemically identical to the initial element but with a mass four units lighter and with different radioactive properties.

Soddy proposed that several types of atoms (differing in radioactive properties) could occupy the same place in the table.

[16] The term "isotope", Greek for "at the same place",[15] was suggested to Soddy by Margaret Todd, a Scottish physician and family friend, during a conversation in which he explained his ideas to her.

[16][27] The first evidence for multiple isotopes of a stable (non-radioactive) element was found by J. J. Thomson in 1912 as part of his exploration into the composition of canal rays (positive ions).

[28] Thomson channelled streams of neon ions through parallel magnetic and electric fields, measured their deflection by placing a photographic plate in their path, and computed their mass to charge ratio using a method that became known as the Thomson's parabola method.

Thomson observed two separate parabolic patches of light on the photographic plate (see image), which suggested two species of nuclei with different mass-to-charge ratios.

He wrote "There can, therefore, I think, be little doubt that what has been called neon is not a simple gas but a mixture of two gases, one of which has an atomic weight about 20 and the other about 22.

"[29] F. W. Aston subsequently discovered multiple stable isotopes for numerous elements using a mass spectrograph.

[30][31] After the discovery of the neutron by James Chadwick in 1932,[32] the ultimate root cause for the existence of isotopes was clarified, that is, the nuclei of different isotopes for a given element have different numbers of neutrons, albeit having the same number of protons.

However, for heavier elements, the relative mass difference between isotopes is much less so that the mass-difference effects on chemistry are usually negligible.

Similarly, two molecules that differ only in the isotopes of their atoms (isotopologues) have identical electronic structures, and therefore almost indistinguishable physical and chemical properties (again with deuterium and tritium being the primary exceptions).

Because vibrational modes allow a molecule to absorb photons of corresponding energies, isotopologues have different optical properties in the infrared range.

Atomic nuclei consist of protons and neutrons bound together by the residual strong force.

The extreme stability of helium-4 due to a double pairing of 2 protons and 2 neutrons prevents any nuclides containing five (52He, 53Li) or eight (84Be) nucleons from existing long enough to serve as platforms for the buildup of heavier elements via nuclear fusion in stars (see triple alpha process).

Of 35 primordial radionuclides there exist four even-odd nuclides (see table at right), including the fissile 23592U.

These stable even-proton odd-neutron nuclides tend to be uncommon by abundance in nature, generally because, to form and enter into primordial abundance, they must have escaped capturing neutrons to form yet other stable even-even isotopes, during both the s-process and r-process of neutron capture, during nucleosynthesis in stars.

Post-primordial isotopes were created by cosmic ray bombardment as cosmogenic nuclides (e.g., tritium, carbon-14), or by the decay of a radioactive primordial isotope to a radioactive radiogenic nuclide daughter (e.g. uranium to radium).

There are about 94 elements found naturally on Earth (up to plutonium inclusive), though some are detected only in very tiny amounts, such as plutonium-244.

[36] Only 251 of these naturally occurring nuclides are stable, in the sense of never having been observed to decay as of the present time.

An additional ~3000 radioactive nuclides not found in nature have been created in nuclear reactors and in particle accelerators.

Before the discovery of isotopes, empirically determined noninteger values of atomic mass confounded scientists.

According to generally accepted cosmology theory, only isotopes of hydrogen and helium, traces of some isotopes of lithium and beryllium, and perhaps some boron, were created at the Big Bang, while all other nuclides were synthesized later, in stars and supernovae, and in interactions between energetic particles such as cosmic rays, and previously produced nuclides.

It is denoted with symbols "u" (for unified atomic mass unit) or "Da" (for dalton).

Isotope separation is a significant technological challenge, particularly with heavy elements such as uranium or plutonium.

Lighter elements such as lithium, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen are commonly separated by gas diffusion of their compounds such as CO and NO.

The separation of hydrogen and deuterium is unusual because it is based on chemical rather than physical properties, for example in the Girdler sulfide process.