Great American Interchange

Others who made significant contributions to understanding the event in the century that followed include Florentino Ameghino, W. D. Matthew, W. B. Scott, Bryan Patterson, George Gaylord Simpson and S. David Webb.

[6] Analogous interchanges occurred earlier in the Cenozoic, when the formerly isolated land masses of India and Africa made contact with Eurasia about 56 and 30 Ma ago, respectively.

[7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][excessive citations] After the late Mesozoic breakup of Gondwana, South America spent most of the Cenozoic era as an island continent whose "splendid isolation" allowed its fauna to evolve into many forms found nowhere else on Earth, most of which are now extinct.

[n 1][n 2] A few non-therian mammals – monotremes, gondwanatheres, dryolestids and possibly cimolodont multituberculates – were also present in the Paleocene; while none of these diversified significantly and most lineages did not survive long, forms like Necrolestes and Patagonia remained as recently as the Miocene.

[31] As the large carnivorous metatherians declined, and before the arrival of most types of carnivorans, predatory opossums such as Thylophorops temporarily attained larger size (about 7 kg).

Metatherians and a few xenarthran armadillos, such as Macroeuphractus, were the only South American mammals to specialize as carnivores; their relative inefficiency created openings for nonmammalian predators to play more prominent roles than usual (similar to the situation in Australia).

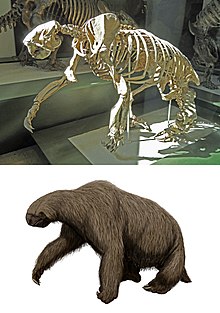

Sparassodonts and giant opossums shared the ecological niches for large predators with fearsome flightless "terror birds" (phorusrhacids), whose closest living relatives are the seriemas.

Through the skies over late Miocene South America (6 Ma ago) soared one of the largest flying birds known, Argentavis, a teratorn that had a wing span of 6 m or more, and which may have subsisted in part on the leftovers of Thylacosmilus kills.

[39] Some of South America's aquatic crocodilians, such as Gryposuchus, Mourasuchus and Purussaurus, reached monstrous sizes, with lengths up to 12 m (comparable to the largest Mesozoic crocodyliforms).

They also produced a number of familiar-looking body types that represent examples of parallel or convergent evolution: one-toed Thoatherium had legs like those of a horse, Pachyrukhos resembled a rabbit, Homalodotherium was a semibipedal, clawed browser like a chalicothere, and horned Trigodon looked like a rhinoceros.

Both groups started evolving in the Lower Paleocene, possibly from condylarth stock, diversified, dwindled before the great interchange, and went extinct at the end of the Pleistocene.

[43][44][45] Their subsequent vigorous diversification displaced some of South America's small marsupials and gave rise to – among others – capybaras, chinchillas, viscachas, and New World porcupines.

[51] Over time, some caviomorph rodents evolved into larger forms that competed with some of the native South American ungulates, which may have contributed to the gradual loss of diversity suffered by the latter after the early Oligocene.

Ucayalipithecus remains dating from the Early Oligocene of Amazonian Peru are, by morphological analysis, deeply nested within the family Parapithecidae of the Afro-Arabian radiation of parapithecoid simians, with dental features markedly different from those of platyrrhines.

Noctilionoid bats ancestral to those in the neotropical families Furipteridae, Mormoopidae, Noctilionidae, Phyllostomidae, and Thyropteridae are thought to have reached South America from Africa in the Eocene,[59] possibly via Antarctica.

They were long thought to have come from North America, but a recent comparative genetic analysis concludes that the South American genus Chelonoidis (formerly part of Geochelone) is actually most closely related to African hingeback tortoises.

[64] Skinks of the related genera Mabuya and Trachylepis apparently dispersed across the Atlantic from Africa to South America and Fernando de Noronha, respectively, during the last 9 Ma.

[n 9] The larger members of the reverse migration were ground sloths, terror birds, glyptodonts, pampatheres, capybaras, and the notoungulate Mixotoxodon (the only South American ungulate known to have invaded Central America).

Northwardly migrating animals often were not able to compete for resources as well as the North American species already occupying the same ecological niches; those that did become established were not able to diversify much, and in some cases did not survive for long.

[89] Southwardly migrating Nearctic species established themselves in larger numbers and diversified considerably more,[89] and are thought to have caused the extinction of a large proportion of the South American fauna.

[n 13] Due in large part to the continued success of the xenarthrans, one area of South American ecospace the Nearctic invaders were unable to dominate was the niches for megaherbivores.

[95] Before 12,000 years ago, South America was home to about 25 species of herbivores weighing more than 1,000 kg (2,200 lb), consisting of Neotropic ground sloths, glyptodonts, and toxodontids, as well as gomphotheres and camelids of Nearctic origin.

The connection between the east Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean (the Central American Seaway) was severed, setting now-separated populations on divergent evolutionary paths.

Purported ecological counterparts between pairs of analogous groups (thylacosmilids and saber-toothed cats, borhyaenids and felids, hathliacynids and weasels) neither overlap in time nor abruptly replace one another in the fossil record.

[120] However, it only managed to colonize a small part of North America for a limited time, failing to diversify and going extinct in the early Pleistocene (1.8 Ma ago); the modest scale of its success has been suggested to be due to competition with placental carnivorans.

The challenge this climatic asymmetry (see map on right) presented was particularly acute for Neotropic species specialized for tropical rainforest environments, which had little prospect of penetrating beyond Central America.

The last of the South and Central American notoungulates and litopterns died out, as well as North America's giant beavers, lions, dholes, cheetahs, and many of its antilocaprid, bovid, cervid, tapirid and tayassuid ungulates.

The near-simultaneity of the megafaunal extinctions with the glacial retreat and the peopling of the Americas has led to proposals that both climate change and human hunting played a role.

Numerous very similar glacial retreats had occurred previously within the ice age of the last several million years without ever producing comparable waves of extinction in the Americas or anywhere else.

Similar megafaunal extinctions have occurred on other recently populated land masses (e.g. Australia,[152][153] Japan,[154] Madagascar,[155] New Zealand,[156] and many smaller islands around the world, such as Cyprus,[157] Crete, Tilos and New Caledonia[158]) at different times that correspond closely to the first arrival of humans at each location.