Glyptodon

Glyptodonts were typically large, quadrupedal (four-legged), herbivorous armadillos with armored carapaces (top shell) that were made of hundreds of interconnected osteoderms (structures in dermis composed of bone).

[4] The unusual fossils consisted of a femur, carapace fragments, and a caudal tube (an armored tail covering found in glyptodontines) that he collected from the Pleistocene aged (ca.

[6][4] Larrañaga wrote to French scientist Auguste Saint Hilaire about the discovery, and the letter was reproduced by Cuvier in 1823 in the second volume of his landmark book Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles.

[6][7] Another work on the armored Megatherium hypothesis was published in 1833 by Berlin scientist E. D'Alton, who described more of the material sent by Sellow, including portions of the limbs, manus, and shoulder girdle.

[5] 1837 saw the naming of the first glyptodontine, Hoplophorus euphractus, when Danish paleontologist Peter Wilhelm Lund published a series of memoirs on the fossils of Lagoa Santa in Brazil, dating to the Pleistocene.

[15][14] In 1838, British diplomat Sir Woodbine Parish (1796–1882) was sent an isolated molariform and a letter about the discovery of several large fossils from the Matanza River in Buenos Aires, Argentina that dated to the Pleistocene.

[16][17] Parish later collected several more fossils from localities in Las Averias and Villanueva; the latter preserved the most complete skeleton which included a mandible fragment, partial limbs, and unguals of a single individual.

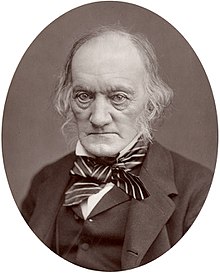

[13][17] Glyptodon was named by Richard Owen (1804–1892), one of the most influential British naturalists of the Victorian Era, writing a chapter about the animal and publishing a reconstruction of its skeleton in the book Buenos Ayres, and the provinces of the Rio de La Plata: their present state, trade, and debt in 1839.

[17] In 1860, Signor Maximo Terrero collected a partial skeleton, including a skull and carapace, of G. clavipes from the River Salado in southern Buenos Aires and dated to the Pleistocene.

[27] Another species now seen as valid, G. munizi, was described in 1881 by Argentine paleontologist Florentino Ameghino (1853–1911) on the basis of several osteoderms found in the Ensenadan of Arroyo del Medio, San Nicolás, Argentina.

[30][17] In 1908, Florentino Ameghino named another species of Glyptodon, G. chapalmalensis, based on a carapace fragment that he had collected from the Atlantic Coast of Buenos Aires Province that dated to the Chapadmalalan.

[17] Yet another genus was erected in 1976 named Heteroglyptodon genuarioi by F. L. Roselli based on an incomplete skeleton that had been collected from the Pleistocene aged Libertad Formation in Nueva Palmira, Uruguay,[34][35] but it has since been found to be an indeterminate specimen of Glyptodon.

[36] Another Glyptodon species was described in 2020 called G. jatunkhirkhi by several authors led by Argentine zoologist Francisco Cuadrelli on the basis of an individual preserving a nearly complete carapace, several caudal rings, and a pelvis that had been collected from Yamparaez, 24 kilometres (15 mi) southeast of the Bolivian city of Sucre.

[19] The family Glyptodontidae was not named until 1869 by John Edward Gray, who included the genera Glyptodon, Panochthus, and Hoplophorus within the group and believed that it was diagnosed by an immovable carapace that was fused to the pelvis.

[41] However, Hermann Burmeister proposed the name Biloricata for the family, believing that glyptodontines possessed a ventral plastron (bottom shell) and could pull their heads inside their carapaces like turtles.

[12][28] Glyptodontinae was classified in its own family or even superfamily until in 2016, when ancient DNA was extracted from the carapace of a 12,000 year old Doedicurus specimen, and a nearly complete mitochondrial genome was reconstructed (76x coverage).

[40] Based on this and the fossil record, glyptodonts would have evolved their characteristic shape and large size (gigantism) quite rapidly, possibly in response to the cooling, drying climate and expansion of open savannas.

The following phylogenetic analysis was conducted by Frédéric Delsuc and colleagues in 2016 and represents the phylogeny of Cingulata using ancient DNA from Doedicurus to determine the position of it and other Glyptodonts:[42][40] Dasypodidae Euphractus Zaedyus Chaetophractus villosus Chaetophractus nationi C. vellerosus †Glyptodontinae (Doedicurus) Chlamyphorus Calyptophractus Priodontes Tolypeutes Cabassous The internal phylogeny of Glyptodontinae is convoluted and in flux, with many species and families erected based on fragmentary or undiagnostic material that lacks comprehensive review.

The angle between the occlusal plane (part of the jaw where upper and lower teeth contact) and the anterior margin of the ascending ramus is approximately 60 in Glyptotherium, while it is 65° in Glyptodon.

[5] Glyptodon's osteoderms were attached by synotoses (bony connections) and were found in double or triple rows on the front and sides of the carapace's edges, as well as in the tail armor and cephalic shield.

Most of the osteoderms of the distal row (some individuals preserving up to 12) bear prominent conical outlines, in stark contrast to more advanced glyptodontines like Doedicurus and Panochthus, which had completely fused tails that formed an inflexible mace or club.

[27][71] However, the evolution of a rigid carapace as opposed to a flexible one in extant armadillos as well as a weakly developed deltoid crest on the humerus (upper arm bone) provided evidence against fossorial hypotheses.

[95] Glyptodon is one of the most common Pleistocene glyptodontines with a large range from the lowland Pampas to the towering Andean Mountains of Peru and Bolivia, some fossils found at elevations reaching over 4,100 metres (13,500 ft) above sea level.

[98] The genus had a generalist diet, which allowed it to fill niches in areas that were inaccessible by grazing genera, with G. reticulatus representing up to 90% of the glyptodontine fossils in the Tarija Valley of Bolivia.

[98][17] Further evidence of Glyptodon's adaptability is found in the Pampas, which were semihumid and temperate from 30,000 to 11,000 ka, alternating between the rainy and dry seasons, over a large area consisting mostly of grasslands dotted with forests and mixed shrubbery.

[102][103] G. jatunkhirkhi specifically is known only from Andean climate of Eastern Cordillera in Bolivia, causing it to evolve to be smaller in size than lowland species due to less support for larger masses.

[97][26] During the Ensenadan and Marplatan, Glyptodon coexisted with a variety of mammals unique to the period such as the notoungulate Mesotherium, canid Theriodictis, and a species of the giant bear Arctotherium.

[101] In areas such as Uruguay, fossils of Glyptodon have been unearthed alongside the contemporary glyptodontines Doedicurus, Neuryurus, Panochthus; armadillos Chaetophractus, Propaeopus, and Eutatus; and the herbivorous pampathere Pampatherium.

[107] Instead, it was found that Glyptodon as well as herbivorous mammals living in denser forests made up a smaller portion of carnivore diets, whereas open grazers such as Lestodon and Macrauchenia were consumed more often.

[121] Evidence from the Campo Laborde and La Moderna archaeological sites in the Argentine Pampas suggest that Glyptodon's relatives Doedicurus and Panochthus survived until the Early Holocene, coexisting with humans for a minimum of 4,000 years.