Macrauchenia

[6] This has historically been argued to correspond to the presence of a tapir-like proboscis, though recent authors suggest a moose-like prehensile lip[7] or a saiga antelope-like nose to filter dust are more likely.

Only one species is generally considered valid,[8] M. patachonica, which was described by Richard Owen based on remains discovered by Charles Darwin during the voyage of the Beagle.

[6] Macrauchenia is thought to have been a mixed feeder that both consumed woody vegetation and grass that lived in herds and probably engaged in seasonal migrations.

[10] As a non-expert he tentatively identified the leg bones and fragments of spine he found as "some large animal, I fancy a Mastodon".

[8] Macrauchenia boliviensis from the probably early Miocene aged Kollukollu Formation of Bolivia described by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1860 is now considered to be an indeterminate member of Macraucheniidae.

[13] The species Macrauchenia ensenadensis described by Florentino Ameghino in 1888 from the Early Pleistocene has been transferred to the closely related genus Macraucheniopsis.

Sequences of mitochondrial DNA extracted from remains of M. patachonica found in a cave in southern Chile published in 2017 indicates that the closest living relatives of Macrauchenia (and by inference, Litopterna) are members of the extant ungulate order Perissodactyla (which includes the equids, rhinoceroses, and tapirs), with litopterns estimated to have genetically diverged from perissodactyls around 66 million years ago.

[16][17] Analysis of collagen sequences obtained from Macrauchenia and the contemporaneous large rhinoceros-like South American ungulate Toxodon, which belongs to another SANU order, Notoungulata, in 2015 reached a similar conclusion and suggests that litopterns are more closely related to notoungulates than to perissodactyls.

[1] The family to which Macrauchenia belongs, Macraucheniidae, first appeared during the Late Eocene or Oligocene, around 39-30 million years ago, depending on what species are included.

[15] The cause of this diversity decline is uncertain, though it has been suggested to be due to climatic changes,[21] as well as possibly competition/predation from immigrants from North America, who arrived following the formation of the Isthmus of Panama during the Pliocene as part of an event called the Great American Interchange.

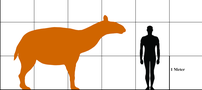

Cladogram of Macraucheniidae after Lobo, Gelfo & Azevedo (2024):[20]Pternoconius Coniopternium Cramauchenia Thesodon Paranauchenia Llullataruca Cullinia Scalabrinitherium Huayqueriana Promacrauchenia Windhausenia Xenorhinotherium Macraucheniopsis Macrauchenia Macrauchenia had a bodyform superficially like a camel,[23] with a long neck composed of camel or giraffe-like elongated cervical vertebrae.

While historically this unusual nasal structure was taken as evidence for a tapir-like probiscis/trunk, recent authors have expressed doubts about this, alternatively suggesting that it may have instead formed a moose-like prehensile lip, or a saiga antelope-like nasal structure which served to filter dust (which was likely prevalent in the environment where Macrauchenia lived),[24] perhaps combining the function of dust filtering organ and a prehensile lip.

While some megafauna remains at the site show clear evidence of exploitation, those of Macrauchenia do not, perhaps because post-depositional degradation of the bones may have erased cut marks.

[38][39] At the El Guanaco site in the Argentinean Pampas, remains of Macrauchenia, alongside those of the glyptodont Doedicurus, horses, and rhea eggshells are associated with stone tools.

[40] At the Paso Otero 5 site in the Pampas of northeast Argentina, burned bones of Macrauchenia alongside those of numerous other extinct megafauna species are associated with Fishtail points (a type of knapped stone spear point common across South America at the end of the Pleistocene, suggested to be used to hunt large mammals[41]).