Disruption of 1843

[6] The main conflict was over whether the Church of Scotland or the British Government had the power to control clerical positions and benefits.

Particularly under John Knox and later Andrew Melville, the Church of Scotland had always claimed an inherent right to exercise independent spiritual jurisdiction over its own affairs.

One of their actions was to pass the Veto Act, which gave parishioners the right to reject a minister nominated by their patron.

The parish of Auchterarder unanimously rejected the patron's nominee – and the Presbytery refused to proceed with his ordination and induction.

As Burleigh puts it: "The notion of the Church as an independent community governed by its own officers and capable of entering into a compact with the state was repudiated" (p. 342).

[12] On 18 May 1843, 121 ministers and 73 elders led by David Welsh met at the Church of St Andrew in George Street, Edinburgh.

[13] After Welsh read a Protest, the group left St. Andrews and walked down the hill to the Tanfield Hall at Canonmills.

The Disruption was basically a spiritual phenomenon – and for its proponents it stood in a direct line with the Reformation and the National Covenants.

Those who left forfeited livings, manses and pulpits, and had, without the aid of the establishment, to found and finance a national church from scratch.

[15] Most of the principles on which the protestors went out were conceded by Parliament by 1929, clearing the way for the re-union of that year, but the Church of Scotland never fully regained its position after the division.

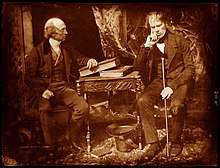

He received encouragement from another spectator, the physicist Sir David Brewster who suggested using the new invention, photography, to get likenesses of all the ministers present, and introduced Hill to the photographer Robert Adamson.

[19] David Octavius Hill's use of photography to record the ministers who participated in the schism of 1843 features in Ali Bacon's novel In the Blink of an Eye (2018).