Industrial Revolution in Scotland

The economic benefits of union were very slow to appear, some progress was visible, such as the sales of linen and cattle to England, the cash flows from military service, and the tobacco trade that was dominated by Glasgow after 1740.

Merchants who profited from the American trade began investing in leather, textiles, iron, coal, sugar, rope, sailcloth, glass-works, breweries, and soap-works, setting the foundations for the city's emergence as a leading industrial center after 1815.

Historians often emphasize that the flexibility and dynamism of the Scottish banking system contributed significantly to the rapid development of the economy in the nineteenth century.

The industrial developments, while they brought work and wealth, were so rapid that housing, town-planning, and provision for public health did not keep pace with them, and for a time living conditions in some of the towns and cities were notoriously bad, with overcrowding, high infant mortality, and growing rates of tuberculosis.

Other factors that also contributed to the process included the improvement of transport links, which helped facilitated the movement of goods, an extensive banking system, and the widespread adoption of ideas about economic development with their origins in the Scottish Enlightenment.

[8] In the first half of the century these changes were limited to tenanted farms in East Lothian and the estates of a few enthusiasts, such as John Cockburn and Archibald Grant.

His rival James Smith turned to improving sub-soil drainage and developed a method of ploughing that could break up the subsoil barrier without disturbing the topsoil.

[11] The development of Scottish agriculture meant that Scotland could support its increased population with food and it released labour that would take part in industrial production.

Historians often emphasise that the flexibility and dynamism of the Scottish banking system contributed significantly to the rapid development of the economy in the nineteenth century.

[16] The extensive Scottish coastline meant that few parts of the country that were not within easy reach of sea transportation, particularly the central belt that would be the heartland of industrial development.

[19] Some progress was visible, such as the sales of linen and cattle to England, the cash flows from military service, and the tobacco trade that was dominated by Glasgow after 1740.

[21] Merchants who profited from the American trade began investing in leather, textiles, iron, coal, sugar, rope, sailcloth, glassworks, breweries, and soapworks, setting the foundations for the city's emergence as a leading industrial centre after 1815.

[27] Scottish industrial policy was made by the Board of Trustees for Fisheries and Manufactures in Scotland, which sought to build an economy complementary, not competitive, with England.

After the cutting off of supplies of raw cotton from 1861 as a result of the American Civil War the country diversified into engineering, shipbuilding, and locomotive construction, with steel replacing iron after 1870.

[38] Coal mining became a major industry, and continued to grow into the twentieth century, producing the fuel to smelt iron, heat homes and factories and drive steam engines locomotives and steamships.

The stereotype emerged early on of Scottish colliers as brutish, non-religious and socially isolated serfs;[43] that was an exaggeration, for their life style resembled coal miners everywhere, with a strong emphasis on masculinity, egalitarianism, group solidarity, and support for radical labour movements.

[47] A good passenger service established by the late 1840s, and a network of freight lines reduced the cost of shipping coal, making products manufactured in Scotland competitive throughout Britain.

The floatation of railway companies was a major factor in the formation of the Scottish stock exchanges and the rise of share holding in Scotland and after the early stages drew in large amounts of English investment.

[48][50] Shipbuilding on Clydeside (the river Clyde through Glasgow and other points) began when the first small yards were opened in 1712 at the Scott family's shipyard at Greenock.

[51] Major firms included Denny of Dumbarton, Scotts Shipbuilding and Engineering Company of Greenock, Lithgows of Port Glasgow, Simon and Lobnitz of Renfrew, Alexander Stephen and Sons of Linthouse, Fairfield of Govan, Inglis of Pointhouse, Barclay Curle of Whiteinch, Connell and Yarrow of Scotstoun.

Equally important were the engineering firms that supplied the machinery to drive these vessels, the boilers and pumps and steering gear – Rankin & Blackmore, Hastie's and Kincaid's of Greenock, Rowan's of Finnieston, Weir's of Cathcart, Howden's of Tradeston and Babcock & Wilcox of Renfrew.

Cost also delayed the transition from iron to steel shipbuilding and as late as 1879 only 18,000 tons of steel-built shipping was launched on the Clyde, 10 per cent of all tonnage.

Most industrial buildings avoided this cast-iron aesthetic, like William Spence's (1806?–83) Elgin Engine Works built in 1856–58, using massive rubble blocks.

The reasons were that low wages limited local consumption, and because there were no important natural resources; thus the Dundee region offered little opportunity for profitable industrial diversification.

[66] The industrial developments, while they brought work and wealth, were so rapid that housing, town-planning, and provision for public health did not keep pace with them, and for a time living conditions in some of the towns and cities were notoriously bad, with overcrowding, high infant mortality, and growing rates of tuberculosis.

This paternalistic policy led many owners to support government sponsored housing programs as well as self-help projects among the respectable working class.

W. H. Fraser argues that the emergence of a class identity can be located to the period before the 1820s, when cotton workers in particular were involved in a series of political protests and events.

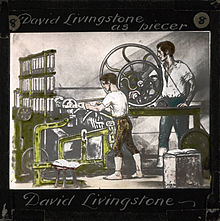

[76] The expanded opportunities for women, and the extra income they and children brought into the household, probably did the most to help increase living standards for working-class families.

[76] From the mid-nineteenth century there were a series of laws that limited female roles in industry, beginning with the Mines and Collieries Act 1842, which prevented them from working underground.

[82] There was little support from the government and in the early stages many migrants agreed to indentures, particularly to the Thirteen Colonies, that paid for their passage and guaranteed accommodation and work for five or seven years.