Great Plague of London

There were gates in the wall at Ludgate, Newgate, Aldersgate, Cripplegate, Moorgate, Bishopsgate and Aldgate, and the Thames was crossable at London Bridge.

The cobbles were slippery with animal droppings, rubbish and the slops thrown out of the houses; they were muddy and buzzing with flies in summer, and awash with sewage in winter.

The City Corporation employed "rakers" to remove the worst of the filth, and it was transported to mounds outside the walls, where it accumulated and continued to decompose.

Another hazard was the choking black smoke belching forth from soap factories, breweries, iron smelters and about 15,000 households that were burning coal to heat their homes.

Some of these areas, both inside the City walls and outside its boundaries, had long been organised into districts of various sizes, called "liberties", that had historically been granted rights to self-government.

Many mistakenly blamed emanations from the earth, "pestilential effluvia", unusual weather, sickness in livestock, abnormal behaviour of animals or an increase in the numbers of moles, frogs, mice or flies.

There was no official census of the population to provide this figure, and the best contemporary count comes from the work of John Graunt (1620–1674), who was one of the earliest Fellows of the Royal Society and one of the first demographers, bringing a scientific approach to the collection of statistics.

In 1662, he estimated that 384,000 people lived in the City of London, the Liberties, Westminster and the out-parishes, based on figures in the Bills of Mortality published each week in the capital.

Anyone who did not report a death to their local church, such as Quakers, Anabaptists, other non-Anglican Christians or Jews, frequently did not get included in the official records.

He suggested a cup of ale and a doubling of their fee to two groats rather than one was sufficient for Searchers to change the cause of death to one more convenient for the householders.

Ships from infected ports were required to moor at Hole Haven on Canvey Island for a trentine – period of 30 days – before being allowed to travel up-river.

A second inspection line was established between the forts on opposite banks of the Thames at Tilbury and Gravesend with instructions to pass only ships with a certificate.

These did not appear as plague deaths on the Bills of Mortality, so no control measures were taken by the authorities, but the total number of people dying in London during the first four months of 1665 showed a marked increase.

A Privy Council committee was formed to investigate methods to best prevent the spread of plague, and measures were introduced to close some of the ale houses in affected areas and limit the number of lodgers allowed in a household.

[33] As cases in St. Giles began to rise, an attempt was made to quarantine the area and constables were instructed to inspect everyone wishing to travel and contain inside vagrants or suspect persons.

He had been only five when the plague struck but made use of his family's recollections (his uncle was a saddler in East London and his father a butcher in Cripplegate), interviews with survivors and sight of such official records as were available.

Yet when the next weeks Bill signifieth to them the disease from nine to three their minds are something appeased; discourse of that subject cools; fears are hushed, and hopes take place, that the black cloud did but threaten, and give a few drops; but the wind would drive it away.

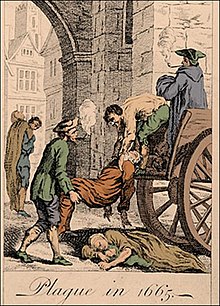

Defoe wrote "Nothing was to be seen but wagons and carts, with goods, women, servants, children, coaches filled with people of the better sort, and horsemen attending them, and all hurrying away".

Ellen Cotes, author of London's Dreadful Visitation, expressed the hope that "Neither the Physicians of our Souls or Bodies may hereafter in such great numbers forsake us".

Before exiting through the city gates, they were required to possess a certificate of good health signed by the Lord Mayor and these became increasingly difficult to obtain.

The refugees were turned back, were not allowed to pass through towns and had to travel across country, and were forced to live rough on what they could steal or scavenge from the fields.

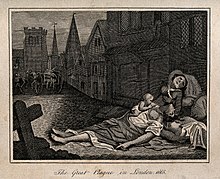

[45] Trade and business had dried up, and the streets were empty of people except for the dead-carts and the dying victims, as witnessed and recorded by Samuel Pepys in his diary: "Lord!

Vincent wrote:it was very dismal to behold the red crosses, and read in great letters "LORD, HAVE MERCY UPON US" on the doors, and watchmen standing before them with halberds...people passing by them so gingerly, and with such fearful looks as if they had been lined with enemies in ambush to destroy them...a man at the corner of Artillery-wall, that as I judge, through the dizziness of his head with the disease, which seized upon him there, had dasht his face against the wall; and when I came by, he lay hanging with his bloody face over the rails, and bleeding upon the ground...I went and spoke to him; he could make no answer, but rattled in the throat, and as I was informed, within half an hour died in the place.

It would be endless to speak of what we have seen and heard, of some in their frenzy, rising out of their beds, and leaping about their rooms; others crying and roaring at their windows; some coming forth almost naked, and running into the streets...scarcely a day passed over my head for, I think, a month or more together, but I should hear of the death of some one or more that I knew.

[50] In Bristol strenuous efforts by the City Council seems to have limited the death rate to c.0.6 per cent during an outbreak lasting from April to September 1666.

[51] By late autumn, the death toll in London and the suburbs began to slow until, in February 1666, it was considered safe enough for the King and his entourage to come back to the city.

Dr Thomas Gumble, chaplain to the Duke of Albemarle, both of whom had stayed in London for the whole of the epidemic, estimated that the total death count for the country from plague during 1665 and 1666 was about 200,000.

It spread to other towns in East Anglia and the southeast of England but fewer than ten per cent of parishes outside London had a higher than average death rate during those years.

Part of this could be accounted for by the return of wealthy households, merchants and manufacturing industries, all of which needed to replace losses among their staff and took steps to bring in necessary people.

Colchester had suffered more severe depopulation, but manufacturing records for cloth suggested that production had recovered or even increased by 1669, and the total population had nearly returned to pre-plague levels by 1674.