Great Wall of China

They were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against various nomadic groups from the Eurasian Steppe.

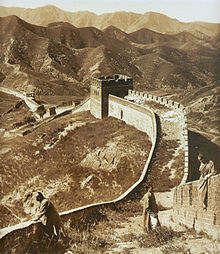

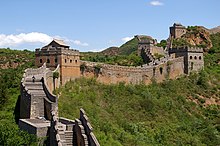

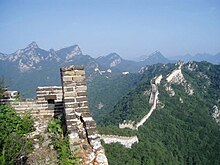

To aid in defense, the Great Wall utilized watchtowers, troop barracks, garrison stations, signaling capabilities through the means of smoke or fire, and its status as a transportation corridor.

[6] The collective fortifications constituting the Great Wall stretch from Liaodong in the east to Lop Lake in the west, and from the present-day Sino–Russian border in the north to Tao River in the south: an arc that roughly delineates the edge of the Mongolian steppe, spanning 21,196.18 km (13,170.70 mi) in total.

[17] Instead, various terms were used in medieval records, including "frontier(s)" (塞, Sài),[18] "rampart(s)" (垣, Yuán),[18] "barrier(s)" (障, Zhàng),[18] "the outer fortresses" (外堡, Wàibǎo),[19] and "the border wall(s)" (t 邊牆, s 边墙, Biānqiáng).

[17] Poetic and informal names for the wall included "the Purple Frontier" (紫塞, Zǐsài)[20] and "the Earth Dragon" (t 土龍, s 土龙, Tǔlóng).

[25][26] Built to withstand the attack of small arms such as swords and spears, these walls were made mostly of stone or by stamping earth and gravel between board frames.

[27] Transporting the large quantity of materials required for construction was difficult, so builders always tried to use local resources; stone was used in montane areas, while rammed earth was used while building in the plains.

[30] Dynasties founded by non-Han ethnic groups also built border walls: the Xianbei-ruled Northern Wei, the Khitan-ruled Liao, Jurchen-led Jin and the Tangut-established Western Xia, who ruled vast territories over Northern China throughout centuries, all constructed defensive walls, albeit being further north—reaching into the environs of present-day Mongolia—than Han-built fortifications.

This defeat had come in the context of protracted conflict with Mongol tribes; a new strategy for defense was thus realized by constructing walls along the northern border of China.

[33] Under general Qi Jiguang's supervision, 1,200 watchtowers from Shanhaiguan Pass to Changping were constructed between 1567 and 1570, and sections of the ram-earth wall were faced with bricks.

It enclosed the agricultural heartland of the Liaodong province, protecting it against potential incursions by Jurchen-Mongol Oriyanghan from the northwest and the Jianzhou Jurchens from the north.

Even after the loss of all of Liaodong, the Ming army held the heavily fortified Shanhai Pass, preventing the Manchus from conquering the Chinese heartland.

Construction nevertheless persisted with projects like the Willow Palisade; following a line similar to that of the Liaodong Wall of the Ming, it was meant to prevent Han Chinese migration into Manchuria.

Possibly one of the earliest European descriptions of the wall and of its significance for the defense of the country against the "Tartars" (i.e. Mongols) may be the one contained in João de Barros's 1563 Asia.

[46] Perhaps the first recorded instance of a European actually entering China via the Great Wall came in 1605, when the Portuguese Jesuit brother Bento de Góis reached the northwestern Jiayu Pass from India.

[50] When China opened its borders to foreign merchants and visitors after its defeat in the First and Second Opium Wars, the Great Wall became a main attraction for tourists.

[53] In addition, Qin, Han and earlier Great Wall sites are 3,080 km (1,914 mi) long in total; Jin dynasty (1115–1234) border fortifications are 4,010 km (2,492 mi) in length; the remainder date back to Northern Wei, Northern Qi, Sui, Tang, the Five Dynasties, Song, Liao and Xixia.

Ruins of the remotest Han border posts are found in Mamitu (t 馬迷途, s 马迷途, Mǎmítú, l "horses losing their way") near Yumen Pass.

From here, the wall travels discontinuously down the Hexi Corridor and into the deserts of Ningxia, where it enters the western edge of the Yellow River loop at Yinchuan.

Here the first major walls erected during the Ming dynasty cut through the Ordos Desert to the eastern edge of the Yellow River loop.

In 2009, 180 km of previously unknown sections of the Ming wall concealed by hills, trenches and rivers were discovered with the help of infrared range finders and GPS devices.

[58] In March and April 2015, nine sections with a total length of more than 10 km (6 mi), believed to be part of the Great Wall, were discovered along the border of Ningxia autonomous region and Gansu province.

[63][64] Communication between the army units along the length of the Great Wall, including the ability to call reinforcements and warn garrisons of enemy movements, was of high importance.

Police described the act as causing "irreversible damage to the integrity of the Ming Great Wall and to the safety of the cultural relics".

[74] One of the earliest known references to the myth of the Great Wall's visibility from the Moon appears in a letter written in 1754 by the English antiquary William Stukeley.

"[75] The claim was also mentioned by Henry Norman in 1895, writing "besides its age it enjoys the reputation of being the only work of human hands on the globe visible from the Moon.

In response, the European Space Agency (ESA) issued a press release reporting of its visibility from an altitude of 160 and 320 km (100 and 200 mi);[74] the image was actually of a river in Beijing.

Based on the photograph, the China Daily later reported that the Great Wall can be seen from 'space' with the naked eye, under favorable viewing conditions, if one knows exactly where to look.