Ancient Greek philosophy

It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics, ontology, logic, biology, rhetoric and aesthetics.

Alfred North Whitehead once claimed: "The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato".

The classicist Martin Litchfield West states, "contact with oriental cosmology and theology helped to liberate the early Greek philosophers' imagination; it certainly gave them many suggestive ideas.

André Laks and Glenn W. Most have been partly responsible for popularizing this shift in describing the era preceding the Athenian School through their comprehensive, nine volume Loeb editions of Early Greek Philosophy.

[11] Thales inspired the Milesian school of philosophy and was followed by Anaximander, who argued that the substratum or arche could not be water or any of the classical elements but was instead something "unlimited" or "indefinite" (in Greek, the apeiron).

[19] Pythagoras lived at approximately the same time that Xenophanes did and, in contrast to the latter, the school that he founded sought to reconcile religious belief and reason.

[20] Pythagoras is said to have been a disciple of Anaximander and to have imbibed the cosmological concerns of the Ionians, including the idea that the cosmos is constructed of spheres, the importance of the infinite, and that air or aether is the arche of everything.

[21] Pythagoreanism also incorporated ascetic ideals, emphasizing purgation, metempsychosis, and consequently a respect for all animal life; much was made of the correspondence between mathematics and the cosmos in a musical harmony.

[23] Heraclitus must have lived after Xenophanes and Pythagoras, as he condemns them along with Homer as proving that much learning cannot teach a man to think; since Parmenides refers to him in the past tense, this would place him in the 5th century BC.

[30] Whereas the doctrines of the Milesian school, in suggesting that the substratum could appear in a variety of different guises, implied that everything that exists is corpuscular, Parmenides argued that the first principle of being was One, indivisible, and unchanging.

[45] Socrates is said to have pursued this probing question-and-answer style of examination on a number of topics, usually attempting to arrive at a defensible and attractive definition of a virtue.

While Socrates' recorded conversations rarely provide a definite answer to the question under examination, several maxims or paradoxes for which he has become known recur.

[48] The great statesman Pericles was closely associated with this new learning and a friend of Anaxagoras, however, and his political opponents struck at him by taking advantage of a conservative reaction against the philosophers; it became a crime to investigate the things above the heavens or below the earth, subjects considered impious.

Epicurus studied with Platonic and Pyrrhonist teachers before renouncing all previous philosophers (including Democritus, on whose atomism the Epicurean philosophy relies).

The philosophic movements that were to dominate the intellectual life of the Roman Empire were thus born in this febrile period following Socrates' activity, and either directly or indirectly influenced by him.

They were also absorbed by the expanding Muslim world in the 7th through 10th centuries AD, from which they returned to the West as foundations of Medieval philosophy and the Renaissance, as discussed below.

The first of these contains the suggestion that there will not be justice in cities unless they are ruled by philosopher kings; those responsible for enforcing the laws are compelled to hold their women, children, and property in common; and the individual is taught to pursue the common good through noble lies; the Republic says that such a city is likely impossible, however, generally assuming that philosophers would refuse to rule and the people would refuse to compel them to do so.

[54] The character of the society described there is eminently conservative, a corrected or liberalized timocracy on the Spartan or Cretan model or that of pre-democratic Athens.

It holds that non-material abstract (but substantial) forms (or ideas), and not the material world of change known to us through our physical senses, possess the highest and most fundamental kind of reality.

[57] This story explains the theory of forms with their different levels of reality, and advances the view that philosopher-kings are wisest while most humans are ignorant.

Aristotle moved to Athens from his native Stageira in 367 BC and began to study philosophy (perhaps even rhetoric, under Isocrates), eventually enrolling at Plato's Academy.

[60] At least twenty-nine of his treatises have survived, known as the corpus Aristotelicum, and address a variety of subjects including logic, physics, optics, metaphysics, ethics, rhetoric, politics, poetry, botany, and zoology.

He criticizes the regimes described in Plato's Republic and Laws,[61] and refers to the theory of forms as "empty words and poetic metaphors".

Aristotle's fame was not great during the Hellenistic period, when Stoic logic was in vogue, but later peripatetic commentators popularized his work, which eventually contributed heavily to Islamic, Jewish, and medieval Christian philosophy.

Aristotle opposed the utopian style of theorizing, deciding to rely on the understood and observed behaviors of people in reality to formulate his theories.

Stemming from an underlying moral assumption that life is valuable, the philosopher makes a point that scarce resources ought to be responsibly allocated to reduce poverty and death.

[64][65] Cutting more along the grain of reality, Aristotle did not only set his mind on how to give people direction to make the right choices but wanted each person equipped with the tools to perform this moral duty.

Socrates had held that virtue was the only human good, but he had also accepted a limited role for its utilitarian side, allowing pleasure to be a secondary goal of moral action.

[71] After returning to Greece, Pyrrho started a new school of philosophy, Pyrrhonism, which taught that it is one's opinions about non-evident matters (i.e., dogma) that prevent one from attaining eudaimonia.

[90] During the Middle Ages, Greek ideas were largely forgotten in Western Europe due to the decline in literacy during the Migration Period.

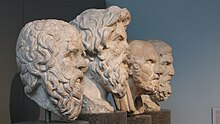

PLISTARCHI • FILIVS

translation (from Latin): Pyrrho • Greek • Son of Plistarchus

HANC ILLIVS IMITARI

SECVRITATEM translation (from Latin): It is right wisdom then that all imitate this security (Pyrrho pointing at a peaceful pig munching his food)