Ancient Greek medicine

Specifically, the ancient Greeks believed health was affected by the humors, geographic location, social class, diet, trauma, beliefs, and mindset.

[1] As trials continued wherein theories were tested against symptoms and results, the pure spiritual beliefs regarding "punishments" and "gifts" were replaced with a foundation based in the physical, i.e., cause and effect.

Moreover, geographic location and social class affected the living conditions of the people and might subject them to different environmental issues such as mosquitoes, rats, and availability of clean drinking water.

Trauma, such as that suffered by gladiators, from dog bites or other injuries, played a role in theories relating to understanding anatomy and infections.

[8] At these shrines, patients would enter a dream-like state of induced sleep known as "enkoimesis" (Greek: ἐγκοίμησις) not unlike anesthesia, in which they either received guidance from the deity in a dream or were cured by surgery.

In the Asclepieion of Epidaurus, three large marble boards dated to 350 BC preserve the names, case histories, complaints, and cures of about 70 patients who came to the temple with a problem and shed it there.

Some of the surgical cures listed, such as the opening of an abdominal abscess or the removal of traumatic foreign material, are realistic enough to have taken place, but with the patient in a state of enkoimesis induced with the help of soporific substances such as opium.

Ancient Greek physicians did not regard disease as being of supernatural origin, i.e., brought about from the dissatisfaction of the gods or demonic possession: "The Greeks developed a system of medicine based on an empirico-rational approach, such that they relied ever more on naturalistic observation, enhanced by practical trial and error experience, abandoning magical and religious justifications of human bodily dysfunction.

"[10] However, in some instances, the fault of the ailment was still placed on the patient and the role of the physician was to conciliate with the gods or exorcise the demon with prayers, spells, and sacrifices.

The Hippocratic Corpus was a body of writing that opposed ancient beliefs, offering biologically based approaches to disease instead of magical intervention.

The establishment of the humoral theory of medicine focused on the balance between blood, yellow and black bile, and phlegm in the human body.

Hippocratic views in the Breasts and Menstruation were rooted in an assumption that the Flesh of a woman was of a completely different essential nature (or physis) compared to that of a man.

While in modern-day physics and chemistry this assumption has been found unhelpful, in zoology and ethology it remains the dominant practice, and Aristotle's work "retains real interest".

In a similar fashion, Aristotle believed that creatures were arranged in a graded scale of perfection rising from plants on up to man—the scala naturae or Great Chain of Being.

For instance, in his writings "History of Animals" he states that men have more skull sutures than women, which demonstrates a larger brain and thinking capacity.

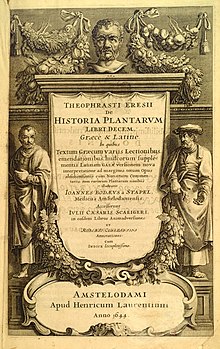

[14] Aristotle's successor at the Lyceum, Theophrastus, wrote a series of books on botany—the History of Plants—which survived as the most important contribution of antiquity to botany, even into the Middle Ages.

[31] The biological/teleological ideas of Aristotle and Theophrastus, as well as their emphasis on a series of axioms rather than on empirical observation, cannot be easily separated from their consequent impact on Western medicine.

The first medical teacher at Alexandria was Herophilus of Chalcedon (the father of anatomy),[34] who differed from Aristotle, placing intelligence in the brain, and connected the nervous system to motion and sensation.

They dissected these criminals alive, and "while they were still breathing they observed parts which nature had formerly concealed, and examined their position, colour, shape, size, arrangement, hardness, softness, smoothness, connection.

[41][42][43] Arguably the most accomplished of all medical researchers of antiquity, Galen influenced the development of various scientific disciplines, including anatomy,[44] physiology, pathology,[45] pharmacology,[46] and neurology, as well as philosophy[47] and logic.

Galen’s extensive body of work, originally written in Greek, provided a foundation for the preservation of medical knowledge that would later be translated into Latin.

[48] The son of Aelius Nicon, a wealthy architect with scholarly interests, Galen received a comprehensive education that prepared him for a successful career as a physician and philosopher.

Born in Pergamon (present-day Bergama, Turkey), Galen traveled extensively, exposing himself to a wide variety of medical theories and discoveries before settling in Rome, where he served prominent members of Roman society and eventually was given the position of personal physician to several emperors.

Galen's understanding of anatomy and medicine was principally influenced by the then-current theory of humorism, as advanced by ancient Greek physicians such as Hippocrates.

[51] Galen's theory of the physiology of the circulatory system endured until 1628, when William Harvey published his treatise entitled De motu cordis, in which he established that blood circulates, with the heart acting as a pump.

Galen conducted many nerve ligation experiments that supported the theory, which is still accepted today, that the brain controls all the motions of the muscles by means of the cranial and peripheral nervous systems.

[55][56][57] Galen was very interested in the debate between the rationalist and empiricist medical sects,[58] and his use of direct observation, dissection and vivisection represents a complex middle ground between the extremes of those two viewpoints.

[59][60][61] The first century AD Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and Roman army surgeon Pedanius Dioscorides authored an encyclopedia of medicinal substances commonly known as De Materia Medica.

The Roman author and natural philosopher Pliny the Elder was a vocal critic, suggesting that Greek doctors were unskilled and motivated by profit rather than healing.

Nevertheless, historian of medicine Vivian Nutton cautions against taking Pliny’s criticism at face value, noting that it underestimates the substantial contributions of Greek physicians.