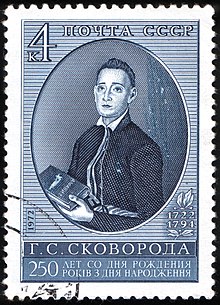

Hryhorii Skovoroda

Different views exist about how to characterize the base language upon which he developed his highly individual idiom.

His mother, Pelageya Stepanovna Shang-Giray, was directly related to Şahin Giray[4] and was of partial Crimean Tatar ancestry.

Many of his philosophical songs known as Skovorodskie psalmy (Skovorodian psalms) were often encountered in the repertoire of blind traveling folk musicians known as kobzars.

In the final quarter of his life he traveled by foot through Sloboda Ukraine staying with various friends, both rich and poor, preferring not to remain in one place for too long.

In this period as well, he continued to write in the area of his greatest earlier achievement: poetry and letters in Church Slavonic language, Greek and Latin.

He requested the following epitaph to be placed on his tombstone:[6] The world tried to capture me, but didn't succeed.He died on 9 November 1794 in the village called Pan-Ivanovka (today is known as Skovorodinovka, Bohodukhiv Raion, Kharkiv Oblast).

"[7] However, except for his works in Latin and Greek, Skovoroda wrote in a mixture of Church Slavonic, Russian, and Ukrainian.

[8] Slavic linguist George Shevelov characterizes his language (not counting quotations from the Bible and numerous poetic experimentations) as "R[ussian] as it was then used in Xarkiv and Slobožаnščyna [Sloboda Ukraine] by educated landowners and the upper class in general," a form of Russian which "grew up on the Ukrainian substratum," contained many Ukrainianisms, and differed from the Russian of Moscow and Saint Petersburg.

Upon this linguistic core, writes Shevelov, Skovoroda developed a very individual idiom not equivalent to its base colloquial language.

[9] In his study of Skovoroda's language published in 1923, linguist Petro Buzuk describes the philosopher's idiom as mainly based on the written Russian of the 18th century, albeit with forms from Ukrainian, Polish and Old Church Slavonic.

According to Vitaly Peredriyenko, 84% of the word forms in Skovoroda's poetry collection Sad bozhestvennykh pesnei (The Garden of Divine Songs) corresponds to the new Ukrainian literary language in terms of vocabulary and word formation; his philosophical dialogues were found to contain a somewhat lower percentage (for example, 73.6% in his Narkiss).

His unusual language was attributed to the influence of his education or the conditions of the time; alternatively, he was accused of "backwardness" and failing to grasp contemporary problems.

[12] The Ukrainian writer Ivan Nechuy-Levytsky called Skovoroda's mixed language "strange, variegated, [and] generally dark.

"[14] In the 1830s, when a group of Romantic authors in Kharkiv was preparing the publication of Skovoroda's works, they considered "translating" his writings into Russian so as not to "frighten away" readers.

[7] According to Shevelov, Skovoroda's stylistic choices were deliberate and not the result of a poor education; the "High Baroque" style that he represented did not attempt to replicate the spoken language in literature.

[16] Individual words, phrases, and quotations in Latin, Greek, and sometimes Hebrew or other languages also appear in his Slavic writings.

Similarly, religious intolerance does not find justification for eternal truth revealed to the world in different forms.

[21][22] In 1751 he had a dispute with the presiding bishop of the Pereyaslav Collegium, who considered Skovoroda's new ways of teaching as strange and incompatible with the former traditional course of poetics.

Young Skovoroda, confident in his mastery of the subject matter and in the precision, clarity and comprehensiveness of his rules of prosody, refused to comply with the bishop's order, asking for arbitration and pointing out to him that "alia res sceptrum, alia plectrum" [the pastor's scepter is one thing, but the flute is another].

He not only excited his students with his lectures but his creative pedagogical approach also attracted the attention of his colleagues and even his superiors.

[25] Skovoroda was also a private tutor for Vasily Tomara (1740—1813) (during 1753–1754, 1755–1758) and a mentor as well as a lifelong friend of Michael Kovalinsky (or Kovalensky, 1745–1807) (during 1761–1769), his biographer.

In his teaching Skovoroda aimed at discovering the student's inclinations and abilities and devised talks and readings which would develop them to the fullest.

"[24][26] His teaching was not limited to academia nor to private friends and during his later years as a "wanderer" he taught publicly the many who were drawn to him.

Archimandrite Gavriil (Vasily Voskresensky, 1795–1868), the first known historian of Russian philosophy,[27] brilliantly described Skovoroda's Socratic qualities in teaching: "Both Socrates and Skovoroda felt from above the calling to be tutors of the people, and, accepting the calling, they became public teachers in the personal and elevated meaning of that word.

… Skovoroda, also like Socrates, not being limited by time or place, taught on the crossroads, at markets, by a cemetery, under church porticoes, during holidays, when his sharp word would articulate an intoxicated will - and in the hard days of the harvest, when a rainless sweat poured upon the earth.

He introduced a well founded idea that a person engaged in an in-born, natural work is provided with a truly satisfying and happy life.

In 1787, seven years before his death, Skovoroda wrote two essays, The Noble Stork (in Original: Благодарный Еродій, Blagorodnyj Erodiy) and The Poor Lark (in Original: Убогій Жаворонокъ, Ubogiy Zhavoronok), devoted to the theme of education where he expounded his ideas.

[30] Skovoroda's broad influence is reflected by the famous writers that appreciated his teachings: Vladimir Solovyov, Leo Tolstoy, Maxim Gorky, Andrei Bely, Taras Shevchenko and Ivan Franko.

Genyk-Berezovská Z. Skovorodův odkaz (Hryhorij Skovoroda a ruská literatura) // Bulletin ruského jazyka a literatury.

Lo Gatto E. L'idea filosofico-religiosa russa da Skovorodà a Solovjòv // Bilychnis: Rivista di studi religiosi.