Group theory

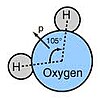

Various physical systems, such as crystals and the hydrogen atom, and three of the four known fundamental forces in the universe, may be modelled by symmetry groups.

One of the most important mathematical achievements of the 20th century[1] was the collaborative effort, taking up more than 10,000 journal pages and mostly published between 1960 and 2004, that culminated in a complete classification of finite simple groups.

The number-theoretic strand was begun by Leonhard Euler, and developed by Gauss's work on modular arithmetic and additive and multiplicative groups related to quadratic fields.

Early results about permutation groups were obtained by Lagrange, Ruffini, and Abel in their quest for general solutions of polynomial equations of high degree.

Felix Klein's Erlangen program proclaimed group theory to be the organizing principle of geometry.

Arthur Cayley and Augustin Louis Cauchy pushed these investigations further by creating the theory of permutation groups.

In many cases, the structure of a permutation group can be studied using the properties of its action on the corresponding set.

For example, in this way one proves that for n ≥ 5, the alternating group An is simple, i.e. does not admit any proper normal subgroups.

This fact plays a key role in the impossibility of solving a general algebraic equation of degree n ≥ 5 in radicals.

A long line of research, originating with Lie and Klein, considers group actions on manifolds by homeomorphisms or diffeomorphisms.

The new paradigm was of paramount importance for the development of mathematics: it foreshadowed the creation of abstract algebra in the works of Hilbert, Emil Artin, Emmy Noether, and mathematicians of their school.

[citation needed] An important elaboration of the concept of a group occurs if G is endowed with additional structure, notably, of a topological space, differentiable manifold, or algebraic variety.

[2] The presence of extra structure relates these types of groups with other mathematical disciplines and means that more tools are available in their study.

Certain classification questions that cannot be solved in general can be approached and resolved for special subclasses of groups.

The properties of finite groups can thus play a role in subjects such as theoretical physics and chemistry.

For example, Fourier polynomials can be interpreted as the characters of U(1), the group of complex numbers of absolute value 1, acting on the L2-space of periodic functions.

They provide a natural framework for analysing the continuous symmetries of differential equations (differential Galois theory), in much the same way as permutation groups are used in Galois theory for analysing the discrete symmetries of algebraic equations.

An extension of Galois theory to the case of continuous symmetry groups was one of Lie's principal motivations.

This occurs in many cases, for example The axioms of a group formalize the essential aspects of symmetry.

Algebraic topology is another domain which prominently associates groups to the objects the theory is interested in.

The presence of the group operation yields additional information which makes these varieties particularly accessible.

Toroidal embeddings have recently led to advances in algebraic geometry, in particular resolution of singularities.

For example, Euler's product formula, captures the fact that any integer decomposes in a unique way into primes.

The failure of this statement for more general rings gives rise to class groups and regular primes, which feature in Kummer's treatment of Fermat's Last Theorem.

Haar measures, that is, integrals invariant under the translation in a Lie group, are used for pattern recognition and other image processing techniques.

Group theory can be used to resolve the incompleteness of the statistical interpretations of mechanics developed by Willard Gibbs, relating to the summing of an infinite number of probabilities to yield a meaningful solution.

Molecular symmetry is responsible for many physical and spectroscopic properties of compounds and provides relevant information about how chemical reactions occur.

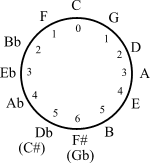

In order to assign a point group for any given molecule, it is necessary to find the set of symmetry operations present on it.

In group theory, the rotation axes and mirror planes are called "symmetry elements".

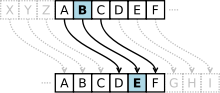

One of the earliest encryption protocols, Caesar's cipher, may also be interpreted as a (very easy) group operation.