Group velocity

[2] The group velocity vg is defined by the equation:[3][4][5][6] where ω is the wave's angular frequency (usually expressed in radians per second), and k is the angular wavenumber (usually expressed in radians per meter).

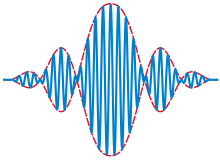

Let A(k) be its Fourier transform at time t = 0, By the superposition principle, the wavepacket at any time t is where ω is implicitly a function of k. Assume that the wave packet α is almost monochromatic, so that A(k) is sharply peaked around a central wavenumber k0.

, describes a perfect monochromatic wave with wavevector k0, with peaks and troughs moving at the phase velocity

The group velocity, therefore, can be calculated by any of the following formulas, Part of the previous derivation is the Taylor series approximation that: If the wavepacket has a relatively large frequency spread, or if the dispersion ω(k) has sharp variations (such as due to a resonance), or if the packet travels over very long distances, this assumption is not valid, and higher-order terms in the Taylor expansion become important.

As a result, the envelope of the wave packet not only moves, but also distorts, in a manner that can be described by the material's group velocity dispersion.

This is an important effect in the propagation of signals through optical fibers and in the design of high-power, short-pulse lasers.

This commonly appears in wireless communication when modulation (a change in amplitude and/or phase) is employed to send data.

To gain some intuition for this definition, we consider a superposition of (cosine) waves f(x, t) with their respective angular frequencies and wavevectors.

means the gradient of the angular frequency ω as a function of the wave vector

In his text "Wave Propagation in Periodic Structures",[11] Brillouin argued that in a lossy medium the group velocity ceases to have a clear physical meaning.

[13] Despite this ambiguity, a common way to extend the concept of group velocity to complex media is to consider spatially damped plane wave solutions inside the medium, which are characterized by a complex-valued wavevector.

Then, the imaginary part of the wavevector is arbitrarily discarded and the usual formula for group velocity is applied to the real part of wavevector, i.e., Or, equivalently, in terms of the real part of complex refractive index, n = n + iκ, one has[14] It can be shown that this generalization of group velocity continues to be related to the apparent speed of the peak of a wavepacket.

[15] The above definition is not universal, however: alternatively one may consider the time damping of standing waves (real k, complex ω), or, allow group velocity to be a complex-valued quantity.

[16][17] Different considerations yield distinct velocities, yet all definitions agree for the case of a lossless, gainless medium.

The above generalization of group velocity for complex media can behave strangely, and the example of anomalous dispersion serves as a good illustration.

may easily become negative (its sign opposes Rek) inside the band of anomalous dispersion.

[18][19][20] Since the 1980s, various experiments have verified that it is possible for the group velocity (as defined above) of laser light pulses sent through lossy materials, or gainful materials, to significantly exceed the speed of light in vacuum c. The peaks of wavepackets were also seen to move faster than c. In all these cases, however, there is no possibility that signals could be carried faster than the speed of light in vacuum, since the high value of vg does not help to speed up the true motion of the sharp wavefront that would occur at the start of any real signal.

Essentially the seemingly superluminal transmission is an artifact of the narrow band approximation used above to define group velocity and happens because of resonance phenomena in the intervening medium.

In a wide band analysis it is seen that the apparently paradoxical speed of propagation of the signal envelope is actually the result of local interference of a wider band of frequencies over many cycles, all of which propagate perfectly causally and at phase velocity.