Envelope (waves)

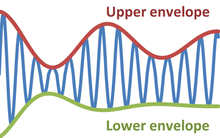

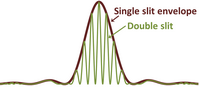

In physics and engineering, the envelope of an oscillating signal is a smooth curve outlining its extremes.

The same amplitude F of the wave results from the same values of ξC and ξE, each of which may itself return to the same value over different but properly related choices of x and t. This invariance means that one can trace these waveforms in space to find the speed of a position of fixed amplitude as it propagates in time; for the argument of the carrier wave to stay the same, the condition is: which shows to keep a constant amplitude the distance Δx is related to the time interval Δt by the so-called phase velocity vp On the other hand, the same considerations show the envelope propagates at the so-called group velocity vg:[5] A more common expression for the group velocity is obtained by introducing the wavevector k: We notice that for small changes Δλ, the magnitude of the corresponding small change in wavevector, say Δk, is: so the group velocity can be rewritten as: where ω is the frequency in radians/s: ω = 2πf.

[7] In condensed matter physics an energy eigenfunction for a mobile charge carrier in a crystal can be expressed as a Bloch wave: where n is the index for the band (for example, conduction or valence band) r is a spatial location, and k is a wavevector.

[9] For example, the wavefunction of a carrier trapped near an impurity is governed by an envelope function F that governs a superposition of Bloch functions: where the Fourier components of the envelope F(k) are found from the approximate Schrödinger equation.

In digital signal processing, the envelope may be estimated employing the Hilbert transform or a moving RMS amplitude.