Dispersion (water waves)

In fluid dynamics, dispersion of water waves generally refers to frequency dispersion, which means that waves of different wavelengths travel at different phase speeds.

As a result, water with a free surface is generally considered to be a dispersive medium.

This section is about frequency dispersion for waves on a fluid layer forced by gravity, and according to linear theory.

A sine wave with water surface elevation η(x, t) is given by:[2] where a is the amplitude (in metres) and θ = θ(x, t) is the phase function (in radians), depending on the horizontal position (x, in metres) and time (t, in seconds):[3] where: Characteristic phases of a water wave are: A certain phase repeats itself after an integer m multiple of 2π: sin(θ) = sin(θ+m•2π).

The dispersion relation will in general depend on several other parameters in addition to the wavenumber k. For gravity waves, according to linear theory, these are the acceleration by gravity g and the water depth h. The dispersion relation for these waves is:[6][5]

An initial wave phase θ = θ0 propagates as a function of space and time.

According to linear theory for waves forced by gravity, the phase speed depends on the wavelength and the water depth.

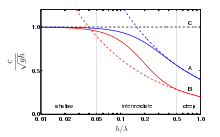

In the left figure, it can be seen that shallow water waves, with wavelengths λ much larger than the water depth h, travel with the phase velocity[2] with g the acceleration by gravity and cp the phase speed.

Since this shallow-water phase speed is independent of the wavelength, shallow water waves do not have frequency dispersion.

Since the phase speed satisfies cp = λ/T = λf, wavelength and period (or frequency) are related.

As a result, the group velocity is, for the limit k1 → k2 :[10][11] Wave groups can only be discerned in case of a narrow-banded signal, with the wave-number difference k1 − k2 small compared to the mean wave number 1/2 (k1 + k2).

The complete theory for linear water waves, including dispersion, was derived by George Biddell Airy and published in about 1840.

A similar equation was also found by Philip Kelland at around the same time (but making some mistakes in his derivation of the wave theory).

[15] The shallow water (with small h / λ) limit, ω2 = gh k2, was derived by Joseph Louis Lagrange.

[16] For two homogeneous layers of fluids, of mean thickness h below the interface and h′ above – under the action of gravity and bounded above and below by horizontal rigid walls – the dispersion relationship ω2 = Ω2(k) for gravity waves is provided by:[17] where again ρ and ρ′ are the densities below and above the interface, while coth is the hyperbolic cotangent function.

For the case ρ′ is zero this reduces to the dispersion relation of surface gravity waves on water of finite depth h. When the depth of the two fluid layers becomes very large (h→∞, h′→∞), the hyperbolic cotangents in the above formula approaches the value of one.

To the third order, and for deep water, the dispersion relation is[19] This implies that large waves travel faster than small ones of the same frequency.

The dot product k•V is equal to: k•V = kV cos α, with V the length of the mean velocity vector V: V = |V|.

Blue lines (A): phase velocity; Red lines (B): group velocity; Black dashed line (C): phase and group velocity √ gh valid in shallow water.

Drawn lines: dispersion relation valid in arbitrary depth.

Dashed lines (blue and red): deep water limits.

Blue lines (A): phase velocity; Red lines (B): group velocity; Black dashed line (C): phase and group velocity √ gh valid in shallow water.

Drawn lines: dispersion relation valid in arbitrary depth.

Dashed lines (blue and red): deep water limits.

| More ... |

|---|

|

In this deep-water case, the phase velocity is twice the group velocity. The red square overtakes two green circles, when moving from the left to the right of the figure.

New waves seem to emerge at the back of a wave group, grow in amplitude until they are at the center of the group, and vanish at the wave group front. For gravity surface-waves, the water particle velocities are much smaller than the phase velocity, in most cases. |

| More ... |

|---|

| For the shown case, a bichromatic group of gravity waves on the surface of deep water, the group velocity is half the phase velocity. In this example, there are 5 + 3 / 4 waves between two wave group nodes in space, while there are 11 + 1 / 2 waves between two wave group nodes in time. |

| More ... |

|---|

| For the three components respectively 22 (bottom), 25 (middle) and 29 (top) wavelengths fit in a horizontal domain of 2,000 meter length. The component with the shortest wavelength (top) propagates slowest. The wave amplitudes of the components are respectively 1, 2 and 1 meter. The differences in wavelength and phase speed of the components results in a changing pattern of wave groups , due to amplification where the components are in phase, and reduction where they are in anti-phase. |

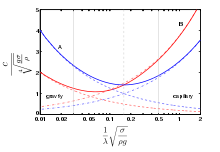

Blue lines (A): phase velocity, Red lines (B): group velocity.

Drawn lines: dispersion relation for gravity-capillary waves.

Dashed lines: dispersion relation for deep-water gravity waves.

Dash-dot lines: dispersion relation valid for deep-water capillary waves.

![{\displaystyle \scriptstyle {\sqrt[{4}]{g\sigma /\rho }}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d5fba378198fe7494e9310dfecd81b655747a78c)