Growth of photovoltaics

When solar PV systems were first recognized as a promising renewable energy technology, subsidy programs, such as feed-in tariffs, were implemented by a number of governments in order to provide economic incentives for investments.

As a consequence, cost of solar declined significantly due to experience curve effects like improvements in technology and economies of scale.

Several national programs were instrumental in increasing PV deployment, such as the Energiewende in Germany, the Million Solar Roofs project in the United States, and China's 2011 five-year-plan for energy production.

[11] The International Energy Agency (IEA) have consistently increased their estimates for decades, while still falling far short of projecting actual deployment in every forecast.

As of 2017[update], a handful of utilities have started combining PV installations with battery banks, thus obtaining several hours of dispatchable generation to help mitigate problems associated with the duck curve after sunset.

[22] The United States was the leader of installed photovoltaics for many years, and its total capacity was 77 megawatts in 1996, more than any other country in the world at the time.

The Carter administration provided major subsidies for research into photovoltaic technology and sought to increase commercialization in the industry.

[30]: 143 Japan took the lead as the world's largest producer of PV electricity, after the city of Kobe was hit by the Great Hanshin earthquake in 1995.

There was massive public outrage when it was revealed that the semigovernmental agency in charge of Monju had tried to cover up the extent of the accident and resulting damage.

Much of China's PV capacity was built in the relatively less populated west of the country whereas the main centres of power consumption were in the east (such as Shanghai and Beijing).

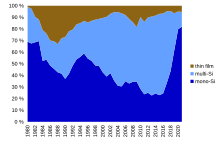

[30]: 143 Chinese firms are the most significant enterprises in almost all parts of the solar manufacturing supply chain, including polysilicon, silicon wafers, batteries, and photovoltaic modules.

[30]: 143 Many of Green's students later became important in China's solar industry, including Shi Zhengrong (who founded Suntech with the support of Wuxi city government).

[48] The sector faced price competition from Chinese crystalline silicon cell and module manufacturers, and some companies together with their patents were sold below cost.

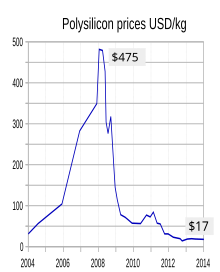

[50]: 24–25 In the early 2000s, prices for polysilicon, the raw material for conventional solar cells, were as low as $30 per kilogram and silicon manufacturers had no incentive to expand production.

[62] Initially, the incumbent polysilicon producers were slow to respond to rising demand for solar applications, because of their painful experience with over-investment in the past.

In 2007, the constraints on silicon became so severe that the solar industry was forced to idle about a quarter of its cell and module manufacturing capacity—an estimated 777 MW of the then available production capacity.

This is notably seen as a "shoulder" that sticks out in the Swanson's PV-learning curve and it was feared that a prolonged shortage could delay solar power becoming competitive with conventional energy prices without subsidies.

Finally, the ramp up of polysilicon production alleviated worldwide markets from the scarcity of silicon in 2009 and subsequently lead to an overcapacity with sharply declining prices in the photovoltaic industry for the following years.

Prices for silicon stabilized around $20 per kilogram and the booming solar PV market helped to reduce the enormous global overcapacity from 2009 onwards.

Continued overcapacity was further reduced by significantly lowering solar module prices and, as a consequence, many manufacturers could no longer cover costs or remain competitive.

As worldwide growth of PV deployment continued, the gap between overcapacity and global demand was expected in 2014 to close in the next few years.

[65] IEA-PVPS published in 2014 historical data for the worldwide utilization of solar PV module production capacity that showed a slow return to normalization in manufacture in the years leading up to 2014.

[67] A year later, the EU also imposed definitive anti-dumping and anti-subsidy measures on imports of solar panels from China at an average of 47.7 percent for a two-year time span.

While worldwide photovoltaic capacity grew continuously, deployment figures by country were much more dynamic, as they depended strongly on national policies.

They include annual and cumulative deployed PV capacity, typically given in watt-peak, a break-down by markets, as well as in-depth analysis and forecasts about future trends.

Reached grid-parity before 2014

Reached grid-parity after 2014

Reached grid-parity only for peak prices

U.S. states poised to reach grid-parity

Source: Deutsche Bank, as of February 2015