Guadeloupe woodpecker

Endemic to the Guadeloupe archipelago in the Lesser Antilles, it is a medium-sized forest woodpecker with entirely black plumage and red-to-purple reflections on its stomach.

During the breeding season, the Guadeloupe woodpecker is solitary bird that nests in holes it digs with its beak in the trunk of dead trees—mainly coconut—where the female lays three to five eggs.

Guadeloupe woodpeckers are mainly insectivorous, but they also feed on small vertebrates like tree frogs and Anolis marmoratus, as well as a variety of seasonal fruits.

The Guadeloupe woodpecker was long considered "near-threatened" according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature due to its endemism, predation of its eggs and nests by black rats, its relatively low numbers, and the specificities of the archipelago—island topography, habitat fragmentation, and urbanization.

5] It is distinct in its appearance within its genus,[19] and unlike other species of Melanerpes, males and females do not present a marked sexual dimorphism in their plumage;[2][20] they are entirely black with gradual reflections ranging from dark red to burgundy on the ventral plumage, dark blue on the back, and metallic blue on the wing tips.

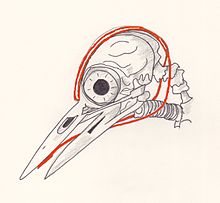

[18] As with all woodpeckers that are adapted to piercing wood, the nostrils on the culmen have small feathers to protect respiration and mucous glands to trap dust.

[22] The pterygoid protractor muscle, which is highly developed in woodpeckers, is important for adapting to shock absorption by uncoupling the beak, which can move laterally, from the skull to minimize the transmission of kinetic energy to the brain and eyes.

The tongue is the result of an evolution of the hyoid apparatus with two parts; one bony at the end is equipped with small hooks, the other cartilaginous lengthens under the action of a branchiomandibular muscle that attaches to the branch of the mandible, split, anchoring on the anterior part at the base of the culmen, surrounding the skull from behind with its two branches, descending on either side of the spine, esophagus and larynx, which pushes the hyoid horns and tongue out of the beak.

[4] The adult Guadeloupe woodpecker feeds mainly on termites, ants, larvae, myriapods, and arthropods—90 percent of which are collected when piercing dead wood—[25] and fruits.

[25] Scientific studies of a captive woodpecker have shown the tip of the bird's long tongue has horny, backward-facing, saliva-coated hooks that allow it to grasp and extract insects from deep holes in wood rather than "harpooning" them.

[22][26] It has been reported the Guadeloupe woodpecker may occasionally and opportunistically feed on a small lizards (Anolis marmoratus), which are also endemic to the archipelago.

[27] Female woodpeckers may occasionally consume crab carcasses during the breeding season to obtain the calcium necessary for the production of their eggshells.

[25] No precise studies of woodpecker feeding, such as identification and quantity of insects consumed, in adults could be made because of the speed of their prey consumption.

[28] The birds' water intake comes from sixteen species of seasonal fruits, the seeds and pits of which they spit out after eating the pulp, violently shaking their heads like all woodpeckers,[29] they have rarely been observed drinking.

[25] Guadeloupe woodpeckers use anvils for cutting up large prey such as frogs and anolis, skinning insects, and cracking open seeds and hard fruits.

[18] It is an exclusive monogamist whose breeding season runs from January to August, with a peak from April to June - indicating a lack of competition in the bird's ecological niche.

7] The 2007 reassessment does not indicate a real increase in their population, which, according to the authors of the two studies, remained stable over the period under consideration.[fn.

8][14] The reduction and fragmentation of its habitat due to human expansion and infrastructure are affecting the balance of its population, especially on Grande-Terre, where it is at risk of extinction.

The species does not fly over non-wooded areas or bodies of water; this trait is increasingly splitting the population into two distinct groups with a moderate degree of genetic differentiation.

[14][15][40] The further reduction of island endemic bird populations may eventually lead to a bottleneck in their genetic diversity and a decline of the species due to excessive inbreeding [fn.

On Grande-Terre,[10] Guadeloupe woodpeckers are forced to nest in wooden poles of telephone and electricity lines, or in living coconut trees, both of which are difficult to excavate; the species has a less-than-20 percent success rate.

[45] Following the last studies on the species' population and habitat in 2007, ornithologists recommended the creation and maintenance of essential vegetation corridors in the center of the island and the installation of dead-coconut-tree sections on the Grande-Terre as artificial nesting boxes.