Slave ship

Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast in West Africa.

[2] In the early 1600s, more than a century after the arrival of Europeans to the Americas,[3] demand for unpaid labor to work plantations made slave-trading a profitable business.

Unhygienic conditions, dehydration, dysentery, and scurvy led to a high mortality rate, on average 15%[5] and up to a third of captives.

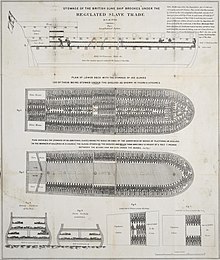

The slaves were naked and shackled together with several different types of chains, stored on the floor beneath bunks with little to no room to move.

Diseases such as dysentery, diarrhea, ophthalmoparesis, malaria, smallpox, yellow fever, scurvy, measles, typhoid fever, hookworm, tapeworm, sleeping sickness, trypanosomiasis, yaws, syphilis, leprosy, elephantiasis, and melancholia resulted in the deaths of slaves on board slave ships.

[1] Olaudah Equiano was among the supporters of the act, but it was opposed by some abolitionists, such as William Wilberforce, who feared it would establish the idea that the slave trade simply needed reform and regulation, rather than complete abolition.

[12] Slave counts can also be estimated by deck area rather than registered tonnage, which results in a lower number of errors and only 6% deviation from reported figures.

[13] This limited reduction in the overcrowding on slave ships may have reduced the on-board death rate, but this is disputed by some historians.

[14] In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the sailors on slave ships were often poorly paid and subject to brutal discipline and treatment.

[15] Furthermore, a crew mortality rate of around 20% was expected during a voyage, with sailors dying as a result of disease, flogging, or slave uprisings.

A high crew mortality rate on the return voyage was in the captain's interests, as it reduced the number of sailors who had to be paid on reaching the home port.