Union blockade

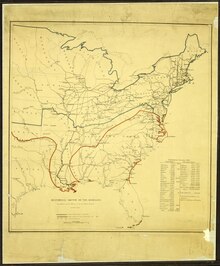

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required the monitoring of 3,500 miles (5,600 km) of Atlantic and Gulf coastline, including 12 major ports, notably New Orleans and Mobile.

The blockade was successful in blocking 95% of cotton exports from the South compared to pre-war levels, devaluing its currency and severely damaging its economy.

Done at the City of Washington, this nineteenth day of April, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-one, and of the Independence of the United States the eighty-fifth.

It became an early base of operations for further expansion of the blockade along the Atlantic coastline,[10] including the Stone Fleet of old ships deliberately sunk to block approaches to Charleston, South Carolina.

[11] Another early prize was Ship Island, which gave the Navy a base from which to patrol the entrances to both the Mississippi River and Mobile Bay.

U.S. warships patrolling abroad were recalled, a massive shipbuilding program was launched, civilian merchant and passenger ships were purchased for naval service, and captured blockade runners were commissioned into the navy.

More than 50,000 men volunteered for the boring duty, because food and living conditions on ship were much better than the infantry offered, the work was safer, and especially because of the real (albeit small) chance for big money.

The blockade runners therefore relied mainly on new steamships built in Britain with low profiles, shallow draft, and high speed.

On each trip, a runner carried several hundred tons of compact, high-value cargo such as cotton, turpentine or tobacco outbound, and rifles, medicine, brandy, lingerie and coffee inbound.

On the other hand, their bravery and initiative were necessary for the rebellion's survival, and many women in the back country flaunted imported $10 gewgaws and $50 hats to demonstrate the Union had failed to isolate them from the outer world.

The government in Richmond, Virginia, eventually regulated the traffic, requiring half the imports to be munitions; it even purchased and operated some runners on its own account and made sure they loaded vital war goods.

[25] In May 1865, CSS Lark became the last Confederate ship to slip out of a Southern port and successfully evade the Union blockade when she left Galveston, Texas, for Havana.

The interdiction of coastal traffic meant that long-distance travel now depended on the rickety railroad system, which never overcame the devastating impact of the blockade.

Throughout the war, the South produced enough food for civilians and soldiers, but it had growing difficulty in moving surpluses to areas of scarcity and famine.

[21] The blockade also largely reduced imports of food, medicine, war materials, manufactured goods, and luxury items, resulting in severe shortages and inflation.

Another consequence, perhaps not intended but highly significant, was the crippling of the interstate slave trade; any shipping route, navigable inland waterway, or railroad that had been used to transport cotton was also used to move "negroes" around the country.

The blockade both prevented the South from efficiently deploying its foundational labor force and disrupted free flow of one of the key sources of cash and collateral in the Confederate economy.

[32] For example, the autobiography of H. C. Bruce recalled the collapse of the business of Negro-Trader White, who had spent the better part of 30 years profiting from chattel arbitrage : "From 1862 to the close of the war, slave property in the state of Missouri was almost a dead weight to the owner; he could not sell because there were no buyers.

Salt was necessary for curing meat; its lack led to significant hardship in keeping the Confederate forces fed as well as severely impacting the populace.

Following the U.S. announcement of its intention to establish an official blockade of Confederate ports, foreign governments began to recognize the Confederacy as a belligerent in the Civil War.

Great Britain had a good amount of cotton stored up in warehouses in several locations that would provide for their textile needs for some time.

[35] The wealth created by the cotton boom caused by the Union blockade led to the redevelopment of much of Cairo and Alexandria as much of the medieval cores of both cities were razed to make way for modern buildings.

Within the next two weeks, Flag Officer Garrett J. Pendergrast had captured 16 enemy vessels, serving early notice to the Confederate War Department that the blockade would be effective if extended.

[45] The first attack failed, but with a change in tactics (and Union generals), the fort fell in January 1865, closing the last major Confederate port.

British investors frequently made the mistake of reinvesting their profits in the trade; when the war ended they were stuck with useless ships and rapidly depreciating cotton.

The fall of Fort Fisher and the city of Wilmington, North Carolina, early in 1865 closed the last major port for blockade runners, and in quick succession Richmond was evacuated, the Army of Northern Virginia disintegrated, and General Lee surrendered.

After the war, former Confederate Navy officer and Lost Cause proponent Raphael Semmes contended that the announcement of a blockade had carried de facto recognition of the Confederate States of America as an independent national entity since countries do not blockade their own ports but rather close them (See Boston Port Act).

To avoid conflict between the United States and Britain over the searching of British merchant vessels thought to be trading with the Confederacy, the Union needed the privileges of international law that came with the declaration of a blockade.

Semmes contends that by effectively declaring the Confederate States of America to be belligerents—rather than insurrectionists, who under international law were not eligible for recognition by foreign powers—Lincoln opened the way for Britain and France potentially to recognize the Confederacy.