Gunpowder weapons in the Ming dynasty

In the Siege of Suzhou of 1366, the Ming army fielded 2,400 large and small cannons in addition to 480 trebuchets, but neither were able to breach the city walls despite "the noise of the guns and the paos went day and night and didn't stop.

[20] The Ming dynasty founder Zhu Yuanzhang, who declared his reign to be the era of Hongwu, or "Great Martiality," made prolific use of gunpowder weapons for his time.

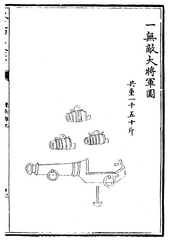

[27] The Hongwu Emperor created a Bureau of Armaments (軍器局) which was tasked with producing every three years 3,000 handheld bronze guns, 3,000 signal cannons, and ammunition as well as accoutrements such as ramrods.

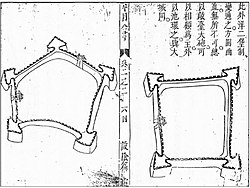

[29] Some exceptionally large cannons exist such as three specimens cast in 1377, each around one meter in length, supported by two trunnions on each side, weighing over 150 kg, and with a muzzle diameter of 21 cm.

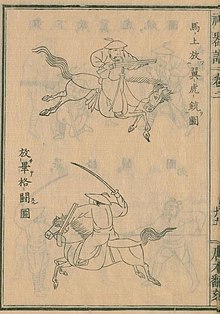

Asianist Kenneth Chase argues that gun development stagnated during the Ming dynasty due to the type of enemy faced by the Chinese: horse nomads.

[38] Guns were supposedly problematic to deploy against nomads because of their size and slow speed, drawing out supply chains, and creating logistical challenges.

The military scholar Weng Wanda goes as far as to claim that only with firearms could one hope to succeed against the fast moving Mongols, and purchased special guns for both the Great Wall defenses and offensive troops who fought in the steppes.

Andrade also points out that Chase downplays the amount of warfare going on outside of the northern frontier, specifically southern China where huge infantry battles and sieges such as in Europe were the norm.

When the Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang died, the civil war which ensued had Chinese armies fighting one another, again with equally powerful firearms.

After the usurper Yongle's victory, the Ming embarked upon yet another five expeditions into Mongolia alongside an invasion of Dai Viet, many of their troops wielding firearms.

[42] According to Tonio Andrade, Chinese firearm development was not hindered by metallurgy, which was sophisticated in China, and the Ming dynasty did construct large guns in the 1370s, but never followed up afterwards.

Nor was it the lack of warfare, which other historians have suggested to be the case, but does not stand up to scrutiny as walls were a constant factor of war which stood in the way of many Chinese armies since time immemorial into the twentieth century.

Chinese walls used a variety of different materials depending on the availability of resources and the time period — ranging from stones to bricks to rammed earth.

[55]During Second Sino-Japanese War, the Japanese also found some difficulty breaching the rammed earth walls of Nanjing: We fought our way to Nanking and joined in the attack on the enemy capital in December.

[56]Andrade goes on to question whether or not Europeans would have developed large artillery pieces in the first place had they faced the more formidable Chinese style walls, coming to the conclusion that such exorbitant investments in weapons unable to serve their primary purpose would not have been ideal.

Once the enemy was within range, each layer would fire in succession, and afterwards a unit armed with traditional close combat weapons would move forward ahead of the musketeers.

Gas leaking limited the effectiveness of these weapons and could even pose a danger to the user due to the close proximity of the matchlock mechanism.

[86] The "rapid thunder gun", developed by Zhao Shizhen, was a five-barreled firearm with a rotating stock fixed to a round shield through the middle.

[89] The hongyipao played a pivotal role in the Ming defense against the Jurchens at the Battle of Ningyuan, but the technological advantage didn't last long.

[90] Chinese gunsmiths continued to modify "red barbarian" cannons after they entered the Ming arsenal, and eventually improved upon them by applying native casting techniques to their design.

[91] According to the soldier Albrecht Herport, who fought for the Dutch at the Siege of Fort Zeelandia, the Chinese "know how to make very effective guns and cannons, so that it’s scarcely possible to find their equal elsewhere.

"[34] Soon after the Ming started producing the composite metal Dingliao grand generals in 1642, Beijing was captured by the Manchu Qing dynasty and along with it all of northern China.

The Manchu elite did not concern themselves directly with guns and their production, preferring instead to delegate the task to Chinese craftsmen, who produced for the Qing a similar composite metal cannon known as the "Shenwei grand general."

[4] After the Battle of Taku Forts (1860), the British reported with surprise that some of the Chinese cannons were of composite structure with similar features to the Armstrong Whitworth guns.

Although the southern Chinese started making cannons with iron cores and bronze outer shells as early as the 1530s, they were followed soon after by the Gujarats, who experimented with it in 1545, the English at least by 1580, and Hollanders in 1629.

However the effort required to produce these weapons prevented them from mass production.The Europeans essentially treated them as experimental products, resulting in very few surviving pieces today.

The four fuses are necessary to prevent the flame going out as the bomb is dropped, [At the moment of explosion, even the coating can cause some damage, but in a trice the calthrops are scattered all over the ground, while the fire-rats rush about in confusion, burning the soldiers.

The "ground thunder explosive camp" was a large group of mines made of bamboo tubes filled with oil, gunpowder, and lead or iron pellets.

The "self tripped trespass land mine" operated in a similar fashion, except the container was made of iron, rock, porcelain or earthenware.

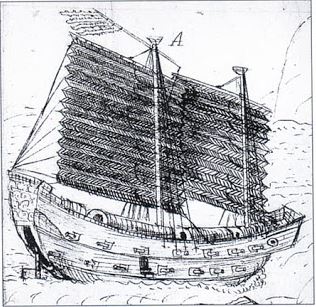

[101] For naval mines, the Huolongjing describes the use of slowly burning joss sticks that were disguised and timed to explode against enemy ships nearby: The sea-mine called the 'submarine dragon-king' is made of wrought iron, and carried on a (submerged) wooden board, [appropriately weighted with stones].