History of gunpowder

The gradual improvement of cannons firing heavier rounds for a greater impact against fortifications led to the invention of the star fort and the bastion in the Western world, where traditional city walls and castles were no longer suitable for defense.

[2] The earliest possible reference to gunpowder appeared in 142 AD during the Eastern Han dynasty when the alchemist Wei Boyang, also known as the "father of alchemy",[3] wrote about a substance with gunpowder-like properties.

[9] While it was almost certainly not their intention to create a weapon of war, Taoist alchemists continued to play a major role in gunpowder development due to their experiments with sulfur and saltpeter involved in searching for eternal life and ways to transmute one material into another.

The "Inner Chapters" (neipian) on Taoism contains records of his experiments to create gold with heated saltpeter, pine resin, and charcoal among other carbon materials, resulting in a purple powder and arsenic vapours.

The Taoist text warned against an assortment of dangerous formulas, one of which corresponds with gunpowder: "Some have heated together sulfur, realgar (arsenic disulfide), and saltpeter with honey; smoke [and flames] result, so that their hands and faces have been burnt, and even the whole house burned down.

"[10] Alchemists called this discovery fire medicine ("huoyao" 火藥), and the term has continued to refer to gunpowder in China into the present day, a reminder of its heritage as a side result in the search for longevity increasing drugs.

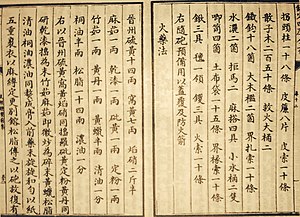

[21] The Wujing Zongyao served as a repository of antiquated or fanciful weaponry, and this applied to gunpowder as well, suggesting that it had already been weaponized long before the invention of what would today be considered conventional firearms.

Early gunpowder may have only produced an effective flame when exposed to oxygen, thus the rush of air around the arrow in flight would have provided a suitably ample supply of reactants for the reaction.

The Song commander "ordered that gunpowder arrows be shot from all sides, and wherever they struck, flames and smoke rose up in swirls, setting fire to several hundred vessels.

Jin troops were surprised in their encampment while asleep by loud drumming, followed by an onslaught of crossbow bolts, and then thunderclap bombs, which caused a panic of such magnitude that they were unable to even saddle themselves and trampled over each other trying to get away.

[55] According to the History of Yuan, in 1287, a group of soldiers equipped with hand cannons led by the Jurchen commander Li Ting (李庭) attacked the rebel prince Nayan's camp.

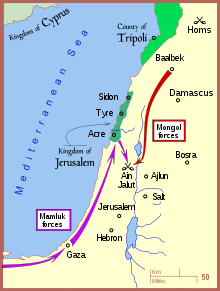

In 1232 the Mongols besieged the Jin capital of Kaifeng and deployed gunpowder weapons along with other more conventional siege techniques such as building stockades, watchtowers, trenches, guardhouses, and forcing Chinese captives to haul supplies and fill moats.

Each troop has hanging on him a little iron pot to keep fire [probably hot coals], and when it's time to do battle, the flames shoot out the front of the lance more than ten feet, and when the gunpowder is depleted, the tube isn't destroyed.

[70] The Mongol war machine moved south and in 1237 attacked the Song city of Anfeng (modern Shouxian, Anhui) "using gunpowder bombs [huo pao] to burn the [defensive] towers.

"[70] The Song defenders under commander Du Gao (杜杲) rebuilt the towers and retaliated with their own bombs, which they called the "Elipao," after a famous local pear, probably in reference to the shape of the weapon.

[33] The next major battle to feature gunpowder weapons was during a campaign led by the Mongol general Bayan, who commanded an army of around two hundred thousand, consisting of mostly Chinese soldiers.

Thus Bayan waited for the wind to change to a northerly course before ordering his artillerists to begin bombarding the city with molten metal bombs, which caused such a fire that "the buildings were burned up and the smoke and flames rose up to heaven.

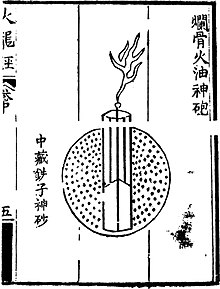

[47] In 1280, a large store of gunpowder at Weiyang in Yangzhou accidentally caught fire, producing such a massive explosion that a team of inspectors at the site a week later deduced that some 100 guards had been killed instantly, with wooden beams and pillars blown sky high and landing at a distance of over 10 li (~2 mi.

[115][116] Al-Rammah's text, The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices (Kitab al-Furusiya wa'l-Munasab al-Harbiya), does however mention fuses, incendiary bombs, naphtha pots, fire lances, and an illustration and description of the earliest torpedo.

From the violence of that salt called saltpeter [together with sulfur and willow charcoal, combined into a powder] so horrible a sound is made by the bursting of a thing so small, no more than a bit of parchment [containing it], that we find [the ear assaulted by a noise] exceeding the roar of strong thunder, and a flash brighter than the most brilliant lightning.

This claim has been disputed by historians of science including Lynn Thorndike, John Maxson Stillman and George Sarton and by Bacon's editor Robert Steele, both in terms of authenticity of the work, and with respect to the decryption method.

[158][159]: 53 Saltpeter harvesting was recorded by Dutch and German travelers as being common in even the smallest villages and was collected from the decomposition process of large dung hills specifically piled for this purpose.

[193] Aside from firearms, the Ming pioneered in the usage of rocket launchers known as "wasp nests", which it manufactured for the army in 1380 and was used by the general Li Jinglong in 1400 against Zhu Di, the future Yongle Emperor.

Although the term arquebus was applied to many different forms of firearms from the 15th to 17th centuries, it was originally used to describe "a hand-gun with a hook-like projection or lug on its under surface, useful for steadying it against battlements or other objects when firing.

[255] The phrase was first coined by Marshall Hodgson in the title of Book 5 ("The Second Flowering: The Empires of Gunpowder Times") of his highly influential three-volume work, The Venture of Islam (1974).

[256] Hogdson applied the term "gunpowder empire" to three Islamic political entities he identified as separate from the unstable, geographically limited confederations of Turkic clans that prevailed in post-Mongol times.

Whether or not gunpowder was inherently linked to the existence of any of these three empires, it cannot be questioned that each of the three acquired artillery and firearms early in their history and made such weapons an integral part of their military tactics.

[271] The 12.9 km long Mont Cenis Tunnel was completed in 13 years starting in 1857 but, even with black powder, progress was only 25 cm a day until the invention of pneumatic drills sped up the work.

The nitre beds were large rectangles of rotted manure and straw, moistened weekly with urine, "dung water", and liquid from privies, cesspools and drains, and turned over regularly.

In the winter of 1863, scores of enslaved people were set to work extracting it from a huge cave in Barstow County, Ga., where they labored by torchlight in grim conditions, hauling out and processing the so-called "peter dirt",.