History of crossbows

In China the crossbow was one of the primary military weapons from the Warring States period until the end of the Han dynasty, when armies were composed of up to 30 to 50 percent crossbowmen.

The small body of evidence and the context they provide point to the fact that the ancient European crossbow was primarily a hunting tool or minor siege weapon.

[7] From the 11th century AD onward, crossbows and crossbowmen occupied a position of high status in medieval European militaries, with the exception of the English and their continued use of the longbow.

[11][12] Bronze crossbow bolts dating from the mid-5th century BC have been found at a Chu burial site in Yutaishan, Jiangling County, Hubei Province.

[23] The Records of the Grand Historian, completed in 94 BC, mentions that Sun Bin defeated Pang Juan by ambushing him with a body of crossbowmen at the Battle of Maling.

[37] Now for piercing through hard things and shooting a long distance, and when struggling to defend mountain-passes, where much noise and impetuous strength must be stemmed, there is nothing like the crossbow for success.

[38] In 169 BC, Chao Cuo observed that by using the crossbow, it was possible to overcome the Xiongnu: Of course, in mounted archery [using the short bow] the Yi and the Di are skilful, but the Chinese are good at using nu che.

The use of sharp weapons with long and short handles by disciplined companies of armoured soldiers in various combinations, including the drill of crossbow men alternately advancing [to shoot] and retiring [to load]; this is something which the Huns cannot even face.

The troops with crossbows ride forward [cai guan shou] and shoot off all their bolts in one direction; this is something which the leather armour and wooden shields of the Huns cannot resist.

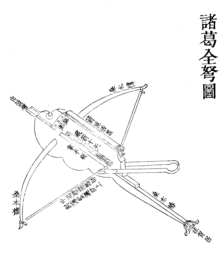

[43] Although hand held repeating crossbows were generally weak and required additional poison, probably aconite, for lethality, much larger mounted versions appeared during the Ming dynasty.

Then, deploying them into a fighting formation, he exploited the wind to engulf the enemy with clouds of lime dust, blinding them, before setting rags on the tails of the horses pulling these driverless artillery wagons alight.

Amidst the obviously great confusion the rebels fired back furiously in self-defense, decimating each other before Yang's forces came up and largely exterminated them.

The Mohist siege crossbow was described as humongous device with frameworks taller than a man and shooting arrows with cords attached so that they could be pulled back.

[54] When Qin Shi Huang's magicians failed to get in touch with "spirits and immortals of the marvellous islands of the Eastern Sea", they excused themselves by saying large monsters blocked their way.

[53]In 950 AD, Tao Gu described multiple crossbows connected by a single trigger: The soldiers at the headquarters of the Xuan Wu army were exceedingly brave.

[57] The 759 CE text, Tai bai yin jing (太白陰經) by Tang military official Li Quan (李筌), contains the oldest known depiction and description of the volley fire technique.

"[57] The Wujing Zongyao, written during the Song dynasty, notes that during the Tang period, crossbows were not used to their full effectiveness due to the fear of cavalry charges.

"[60] Both Tang and Song manuals also made aware to the reader that "the accumulated arrows should be shot in a stream, which means that in front of them there must be no standing troops, and across [from them] no horizontal formations.

The History of Song elaborates on the battle in detail: [Wu] Jie ordered his commanders to select their most vigorous bowmen and strongest crossbowmen and to divide them up for alternate shooting by turns (分番迭射).

The peoples of the northeastern Asia possess it also, both as weapon and toy, but use it mainly in the form of unattended traps; this is true of the Yakut, Tungus, and Chukchi, even of the Ainu in the east.

[67][68][69] The Khmer also had double bow crossbows mounted on elephants, which Michel JacqHergoualc’h suggest were elements of Cham mercenaries in Jayavarman VII's army.

[44] The earliest crossbow-like weapons in Europe probably emerged around the late 5th century BC when the gastraphetes, an ancient Greek crossbow, appeared.

The device was described by the Greco-Roman author Heron of Alexandria of Roman Egypt in his Belopoeica ("On Catapult-making"), which draws on an earlier account of Greek engineer Ctesibius (fl.

[75] Other arrow shooting machines such as the larger ballista and smaller Scorpio also existed starting from around 338 BC, but these are torsion catapults and not considered crossbows.

[80] At the same time, Greek fortifications began to feature high towers with shuttered windows in the top, presumably to house anti-personnel arrow shooters, as in Aigosthena.

Perhaps the best supposition is that the crossbow was primarily known in late European antiquity as a hunting weapon, and received only local use in certain units of the armies of Theodosius I, with which Vegetius happened to be acquainted.

[84]To date, the only contemporary accounts of the arcuballista – the Roman crossbow – appear in the pages of De Re Militaris, written by Vegetius in the late 4th century AD.

And in discharging them the string shoots them out with enormous violence and force, and whatever these darts chance to hit, they do not fall back, but they pierce through a shield, then cut through a heavy iron corselet and wing their way through and out at the other side.

Genoese crossbowmen, recruited in Genoa and in different parts of northern Italy, were famous mercenaries hired throughout medieval Europe, while the crossbow also played an important role in anti-personnel defence of ships.

In China, the crossbow was not considered a serious military weapon by the end of the late Ming dynasty, but continued to see limited usage into the 19th century AD.