Gutenberg Bible

[2][3] In March 1455, the future Pope Pius II wrote that he had seen pages from the Gutenberg Bible displayed in Frankfurt to promote the edition.

[5] While it is unlikely that any of Gutenberg's early publications would bear his name, the initial expense of press equipment and materials and of the work to be done before the Bible was ready for sale suggests that he may have started with more lucrative texts, including several religious documents, a German poem, and some editions of Aelius Donatus's Ars Minor, a popular Latin grammar school book.

In March 1455, the future Pope Pius II wrote that he had seen pages from the Gutenberg Bible, being displayed to promote the edition, in Frankfurt.

[14][15] In a legal paper, written after completion of the Bible, Johannes Gutenberg refers to the process as Das Werk der Bücher ("the work of the books").

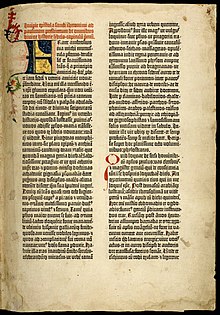

[16] Many book-lovers have commented on the high standards achieved in the production of the Gutenberg Bible, some describing it as one of the most beautiful books ever printed.

Typically, five of these folded sheets (ten leaves, or twenty printed pages) were combined to a single physical section, called a quinternion, that could then be bound into a book.

[24] The Bible's paper consists of linen fibers and is thought to have been imported from Caselle in Piedmont, Italy based on the watermarks present throughout the volume.

His ink was primarily carbon, but also had a high metallic content, with copper, lead, and titanium predominating.

[26] Head of collections at the British Library, Kristian Jensen, described it thus: "if you look [at the pages of The Gutenberg Bible] closely you will see this is a very shiny surface.

The name Textura refers to the texture of the printed page: straight vertical strokes combined with horizontal lines, giving the impression of a woven structure.

Gutenberg already used the technique of justification, that is, creating a vertical, not indented, alignment at the left and right-hand sides of the column.

[29][30] Initially the rubrics—the headings before each book of the Bible—were printed, but this practice was quickly abandoned at an unknown date, and gaps were left for rubrication to be added by hand.

[38][39] Although this made them significantly cheaper than manuscript Bibles, most students, priests or other people of moderate income would not have been able to afford them.

[1] Kristian Jensen suggests that many copies were bought by wealthy and pious laymen for donation to religious institutions.

The Gutenberg Bible also had an influence on the Clementine edition of the Vulgate commissioned by the Papacy in the late sixteenth century.

It was replaced in the fall of 1953, when a patron donated the corresponding leaf from a defective Gutenberg second volume which was being broken up and sold in parts.

[99] In the last hundred years, several long-lost copies have come to light, considerably improving the understanding of how the Bible was produced and distributed.

The leaves were sold in a portfolio case with an essay written by A. Edward Newton, and were referred to as "Noble Fragments".

[100][101] In 1953 Charles Scribner's Sons, also book dealers in New York, dismembered a damaged paper copy of volume II.

[42] The matching first volume of this copy was subsequently discovered in Mons, Belgium, having been bequeathed by Edmond Puissant to the city in 1934.

[14] The only copy held outside Europe and North America is the first volume of a Gutenberg Bible (Hubay 45) at Keio University in Tokyo.

The Humanities Media Interface Project (HUMI) at Keio University is known for its high-quality digital images of Gutenberg Bibles and other rare books.

[70] Under the direction of Professor Toshiyuki Takamiya, the HUMI team has made digital reproductions of 11 sets of the bible in nine institutions, including both full-text facsimiles held in the collection of the British Library.

[2][3] A two-volume paper edition of the Gutenberg Bible was stolen from Moscow State University in 2009 and subsequently recovered in an FSB sting operation in 2013.