History of Marseille

During the 16th century the city hosted a naval fleet with the combined forces of the Franco-Ottoman alliance, which threatened the ports and navies of Genoa and the Holy Roman Empire.

The Industrial Revolution and establishment of the French Empire during the 19th century allowed for further expansion of the city, although it was captured and heavily damaged by Nazi Germany during World War II.

The connection between Massalia and the Phoceans is mentioned in Thucydides's Peloponnesian War;[6] he notes that the Phocaean project was opposed by the Carthaginians, whose fleet was defeated.

According to the legend, Protis (in Aristotle, Euxenes), a native of Phocae, while exploring for a new trading outpost or emporion to make his fortune, discovered the Mediterranean cove of the Lacydon, fed by a freshwater stream and protected by two rocky promontories.

[8] Protis was invited inland to a banquet held by the chief of the local Ligurian tribe, Nann, for suitors seeking the hand of his daughter Gyptis (in Aristotle, Petta) in marriage.

[9] Robb gives greater weight to the Gyptis story, though he notes that the tradition was to offer water, not wine, to signal the choice of a marriage partner.

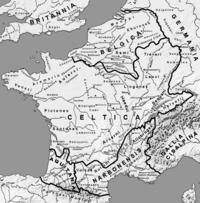

Traders from Massalia ventured into France on the rivers Durance and Rhône and established overland trade routes to Switzerland and Burgundy, reaching as far north as the Baltic Sea.

Pytheas made mathematical instruments, which allowed him to establish almost exactly the latitude of Marseille, and he was the first scientist to observe that the tides were connected with the phases of the moon.

Between 330 and 320 BC, he organized an expedition by ship into the Atlantic and as far north as England, and to visit Iceland, Shetland, and Norway, where he was the first scientist to describe drift ice and the midnight sun.

[12] The city thrived by acting as a link between inland Gaul, hungry for Roman goods and wine (which Massalia was steadily exporting by 500 BC),[13][14] and Rome's insatiable need for new products and slaves.

In 123 BC, Massalia was faced by an invasion of the Allobroges and Arverni under Bituitus; it entered into an alliance with Rome, receiving protection—Roman legions under Q. Fabius Maximus and Gn.

Domitius Ahenobarbus defeated the Gauls at Vindalium in 121 BC—in exchange for yielding a strip of land through its territory which was used to construct the Via Domitia, a road to Spain.

The city thus maintained its independence a little longer, although the Romans organized their province of Transalpine Gaul around it and constructed a colony at Narbo Martius (Narbonne) in 118 BC which subsequently competed economically with Massalia.

The city's laws among other things forbade the drinking of wine by women and allowed, by a vote of the senators, assistance to a person to commit suicide.

The city was not affected by the decline of the Roman Empire before the 8th century, as Marseille enjoyed continued prosperity, probably thanks to its efficient defensive walls inherited from the Phoceans.

Even after the town fell into the hands of the Visigoths in the 5th century, the city became an important Christian intellectual center with people such as John Cassian, Salvian and Sidonius Apollinaris.

Marseille was occupied by Umayyad Arab forces in or before 736 at the invitation of the local ruler, duke Maurontus, as allies against his enemy Charles Martel.

As a major port, it is believed that Marseille was one of the first places in France to encounter the epidemic, and some 15,000 people died in a city that had a population of 25,000 during its period of economic prosperity in the previous century.

King René, who wished to equip the entrance of the port with a solid defense, decided to build on the ruins of the old Maubert tower and to establish a series of ramparts guarding the harbour.

[25] Some 30 years after its incorporation, Francis I visited Marseille, drawn by his curiosity to see a rhinoceros that King Manuel I of Portugal was sending to Pope Leo X, but which had been landed on the Île d'If.

As a result of this visit, the fortress of Château d'If was constructed; this did little to prevent Marseille being placed under siege by the army of the Holy Roman Empire a few years later.

[26][page needed] Marseille became a naval base for the Franco-Ottoman alliance in 1536, as a Franco-Turkish fleet was stationed in the harbour, threatening the Holy Roman Empire and especially Genoa.

A century later more troubles were in store: King Louis XIV himself had to descend upon Marseille, at the head of his army, in order to quash a local uprising against the governor.

The rise of the French Empire and the conquests of France from 1830 onward (notably Algeria) stimulated the maritime trade and raised the prosperity of the city.

[33] This period in Marseille's history is reflected in many of its monuments, such as the Napoleonic obelisk at Mazargues and the royal triumphal arch on the Place Jules Guesde.