Gyrator

Gyrators permit network realizations of two-(or-more)-port devices which cannot be realized with just the four conventional elements.

Although the gyrator was conceived as a fifth linear element, its adoption makes both the ideal transformer and either the capacitor or inductor redundant.

An important property of a gyrator is that it inverts the current–voltage characteristic of an electrical component or network.

An ideal gyrator is a linear two-port device which couples the current on one port to the voltage on the other and conversely.

[3] By convention, the given gyration resistance or conductance relates the voltage on the port at the head of the arrow to the current at its tail.

The voltage at the tail of the arrow is related to the current at its head by minus the stated resistance.

[8] Tellegen named the element gyrator as a blend of gyroscope and the common device suffix -tor (as in resistor, capacitor, transistor etc.)

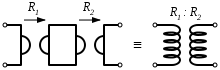

Cascading two gyrators achieves a voltage-to-voltage coupling identical to that of an ideal transformer.

The electric current around the loop then corresponds to the rate-of-change of magnetic flux through the core, and the electromotive force (EMF) in the loop due to each gyrator corresponds to the magnetomotive force (MMF) in the core due to each winding.

Before the invention of the transistor, coils of wire with large inductance might be used in electronic filters.

An inductor can be replaced by a much smaller assembly containing a capacitor, operational amplifiers or transistors, and resistors.

The op-amp follower buffers this voltage and applies it back to the input through the resistor RL.

The desired effect is an impedance of the form of an ideal inductor L with a series resistance RL:

In typical designs, R is chosen to be sufficiently large such that the first term dominates; thus, the RC circuit's effect on input impedance is negligible:

There is a practical limit on the minimum value that RL can take, determined by the current output capability of the op-amp.

In typical applications, both the inductance and the resistance of the gyrator are much greater than that of a physical inductor.

Physical inductors are typically limited to tens of henries, and have parasitic series resistances from hundreds of microhms through the low kilohm range.

Thus, use of capacitors and gyrators may improve the quality of filter networks that would otherwise be built using inductors.

The circuit cannot respond like a real inductor to sudden input changes (it does not produce a high-voltage back EMF); its voltage response is limited by the power supply.

Hence gyrators are usually not very useful for situations requiring simulation of the 'flyback' property of inductors, where a large voltage spike is caused when current is interrupted.

A gyrator's transient response is limited by the bandwidth of the active device in the circuit and by the power supply.

They also don't create magnetic fields (and induce currents in external conductors) the same way that real inductors do.

The primary application for a gyrator is to reduce the size and cost of a system by removing the need for bulky, heavy and expensive inductors.

For example, RLC bandpass filter characteristics can be realized with capacitors, resistors and operational amplifiers without using inductors.

Thus graphic equalizers can be achieved with capacitors, resistors and operational amplifiers without using inductors because of the invention of the gyrator.

Gyrator circuits are extensively used in telephony devices that connect to a POTS system.

This has allowed telephones to be much smaller, as the gyrator circuit carries the DC part of the line loop current, allowing the transformer carrying the AC voice signal to be much smaller due to the elimination of DC current through it.

Also, when systems involving multiple energy domains are being analysed as a unified system through analogies, such as mechanical-electrical analogies, the transducers between domains are considered either transformers or gyrators depending on which variables they are translating.

Such a gyrator can be made with a single mechanical element by using a multiferroic material using its magnetoelectric effect.

This vibration will induce a voltage between electrodes embedded in the material through the multiferroic's piezoelectric property.