Mechanical filter

At the input and output of the filter, transducers convert the electrical signal into, and then back from, these mechanical vibrations.

It is only necessary to set the mechanical components to appropriate values to produce a filter with an identical response to the electrical counterpart.

For example, filtering of audio frequency response in the design of loudspeaker cabinets can be achieved with mechanical components.

A representative selection of the wide variety of component forms and topologies for mechanical filters are presented in this article.

By the 1950s mechanical filters were being manufactured as self-contained components for applications in radio transmitters and high-end receivers.

Contemporary researchers are working on microelectromechanical filters, the mechanical devices corresponding to electronic integrated circuits.

The elements of a passive linear electrical network consist of inductors, capacitors and resistors which have the properties of inductance, elastance (inverse capacitance) and resistance, respectively.

Resistances are not present in a theoretical filter composed of ideal components and only arise in practical designs as unwanted parasitic elements.

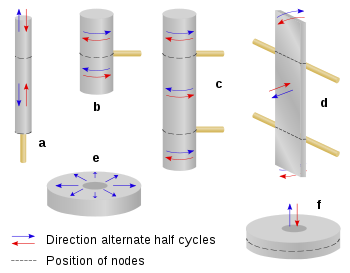

Likewise, a mechanical filter would ideally consist only of components with the properties of mass and stiffness, but in reality some damping is present as well.

[1] The mechanical counterparts of voltage and electric current in this type of analysis are, respectively, force (F) and velocity (v) and represent the signal waveforms.

Equivalent circuits produced by this scheme are similar, but are the dual impedance forms whereby series elements become parallel, capacitors become inductors, and so on.

It is still possible to represent inductors and capacitors as individual lumped elements in a mechanical implementation by minimising (but never quite eliminating) the unwanted property.

[10][11] Versions of the harmonic telegraph were developed by Elisha Gray, Alexander Graham Bell, Ernest Mercadier[b] and others.

[10][11] Once the basics of electrical network analysis began to be established, it was not long before the ideas of complex impedance and filter design theories were carried over into mechanics by analogy.

Once these ideas were in place, engineers were able to extend electrical theory into the mechanical domain and analyse an electromechanical system as a unified whole.

The horn of the phonograph is represented as a transmission line, and is a resistive load for the rest of the circuit, while all the mechanical and acoustic parts—from the pickup needle through to the horn—are translated into lumped components according to the impedance analogy.

The resulting phonograph has a flat frequency response in its passband and is free of the resonances previously experienced.

[1] Norton's mechanical design predates the paper by Butterworth who is usually credited as the first to describe the electronic maximally flat filter.

[21] Another unusual feature of Norton's filter design arises from the series capacitor, which represents the stiffness of the diaphragm.

[25] The idea was taken up by Collins Radio Company who started the first volume production of mechanical filters from the 1950s onwards.

These were originally designed for telephone frequency-division multiplex applications where there is commercial advantage in using high quality filters.

It is possible to dispense with the magnets if the biasing is taken care of on the electronic side by providing a d.c. current superimposed on the signal, but this approach would detract from the generality of the filter design.

It is common practice to add a capacitor in parallel with the coil so that an additional resonator is formed which can be incorporated into the filter design.

For some types of resonator, this can provide a convenient place to make a mechanical attachment for structural support.

[44] The frequency response behaviour of all mechanical filters can be expressed as an equivalent electrical circuit using the impedance analogy described above.

As with the electrical counterpart, the more elements that are used, the closer the approximation approaches the ideal, however, for practical reasons the number of resonators does not normally exceed eight.

The frequency at which the transition from lumped to distributed modeling takes place is much lower for mechanical filters than it is for their electrical counterparts.

A common component used for radio frequency filtering (and MEMS applications generally), is the cantilever resonator.

Experimental complete filters with an operating frequency of 30 GHz have been produced using cantilever varactors as the resonator elements.

[52] Cantilever resonators are typically applied at frequencies below 200 MHz, but other structures, such as micro-machined cavities, can be used in the microwave bands.