Homotopy principle

In mathematics, the homotopy principle (or h-principle) is a very general way to solve partial differential equations (PDEs), and more generally partial differential relations (PDRs).

The h-principle is good for underdetermined PDEs or PDRs, such as the immersion problem, isometric immersion problem, fluid dynamics, and other areas.

The theory was started by Yakov Eliashberg, Mikhail Gromov and Anthony V. Phillips.

It was based on earlier results that reduced partial differential relations to homotopy, particularly for immersions.

which satisfies a partial differential equation of degree

While many underdetermined partial differential equations satisfy the h-principle, the falsity of one is also an interesting statement.

Intuitively this means that the objects being studied have non-trivial geometry which can not be reduced to topology.

As an example, embedded Lagrangians in a symplectic manifold do not satisfy an h-principle, to prove this one can for instance find invariants coming from pseudo-holomorphic curves.

Perhaps the simplest partial differential relation is for the derivative to not vanish:

Properly, this is an ordinary differential relation, as this is a function in one variable.

The space of such functions consists of two disjoint convex sets: the increasing ones and the decreasing ones, and has the homotopy type of two points.

The space of non-holonomic solutions again consists of two disjoint convex sets, according as g(x) is positive or negative.

Thus the inclusion of holonomic into non-holonomic solutions satisfies the h-principle.

This trivial example has nontrivial generalizations: extending this to immersions of a circle into itself classifies them by order (or winding number), by lifting the map to the universal covering space and applying the above analysis to the resulting monotone map – the linear map corresponds to multiplying angle:

Note that here there are no immersions of order 0, as those would need to turn back on themselves.

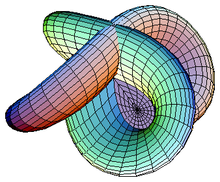

Extending this to circles immersed in the plane – the immersion condition is precisely the condition that the derivative does not vanish – the Whitney–Graustein theorem classified these by turning number by considering the homotopy class of the Gauss map and showing that this satisfies an h-principle; here again order 0 is more complicated.

Smale's classification of immersions of spheres as the homotopy groups of Stiefel manifolds, and Hirsch's generalization of this to immersions of manifolds being classified as homotopy classes of maps of frame bundles are much further-reaching generalizations, and much more involved, but similar in principle – immersion requires the derivative to have rank k, which requires the partial derivatives in each direction to not vanish and to be linearly independent, and the resulting analog of the Gauss map is a map to the Stiefel manifold, or more generally between frame bundles.

The position of a car in the plane is determined by three parameters: two coordinates

In robotics terms, not all paths in the task space are holonomic.

A non-holonomic solution in this case, roughly speaking, corresponds to a motion of the car by sliding in the plane.

In this case the non-holonomic solutions are not only homotopic to holonomic ones but also can be arbitrarily well approximated by the holonomic ones (by going back and forth, like parallel parking in a limited space) – note that this approximates both the position and the angle of the car arbitrarily closely.

This implies that, theoretically, it is possible to parallel park in any space longer than the length of your car.

This last property is stronger than the general h-principle; it is called the

This is also a dense h-principle, and can be proven by an essentially similar "wrinkling" – or rather, circling – technique to the car in the plane, though it is much more involved.

Here we list a few counter-intuitive results which can be proved by applying the h-principle: