Gaussian curvature

The Gaussian curvature can also be negative, as in the case of a hyperboloid or the inside of a torus.

Gaussian curvature is named after Carl Friedrich Gauss, who published the Theorema egregium in 1827.

For most points on most “smooth” surfaces, different normal sections will have different curvatures; the maximum and minimum values of these are called the principal curvatures, call these κ1, κ2.

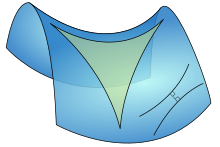

The sign of the Gaussian curvature can be used to characterise the surface.

Most surfaces will contain regions of positive Gaussian curvature (elliptical points) and regions of negative Gaussian curvature separated by a curve of points with zero Gaussian curvature called a parabolic line.

They measure how the surface bends by different amounts in different directions from that point.

We represent the surface by the implicit function theorem as the graph of a function, f, of two variables, in such a way that the point p is a critical point, that is, the gradient of f vanishes (this can always be attained by a suitable rigid motion).

This definition allows one immediately to grasp the distinction between a cup/cap versus a saddle point.

A useful formula for the Gaussian curvature is Liouville's equation in terms of the Laplacian in isothermal coordinates.

The total curvature of a geodesic triangle equals the deviation of the sum of its angles from π.

The sum of the angles of a triangle on a surface of positive curvature will exceed π, while the sum of the angles of a triangle on a surface of negative curvature will be less than π.

On a surface of zero curvature, such as the Euclidean plane, the angles will sum to precisely π radians.

Gauss's Theorema egregium (Latin: "remarkable theorem") states that Gaussian curvature of a surface can be determined from the measurements of length on the surface itself.

In fact, it can be found given the full knowledge of the first fundamental form and expressed via the first fundamental form and its partial derivatives of first and second order.

Equivalently, the determinant of the second fundamental form of a surface in R3 can be so expressed.

The "remarkable", and surprising, feature of this theorem is that although the definition of the Gaussian curvature of a surface S in R3 certainly depends on the way in which the surface is located in space, the end result, the Gaussian curvature itself, is determined by the intrinsic metric of the surface without any further reference to the ambient space: it is an intrinsic invariant.

In particular, the Gaussian curvature is invariant under isometric deformations of the surface.

To connect this point of view with the classical theory of surfaces, such an abstract surface is embedded into R3 and endowed with the Riemannian metric given by the first fundamental form.

Theorema egregium is then stated as follows: The Gaussian curvature of an embedded smooth surface in R3 is invariant under the local isometries.

[1][page needed] On the other hand, since a sphere of radius R has constant positive curvature R−2 and a flat plane has constant curvature 0, these two surfaces are not isometric, not even locally.

Thus any planar representation of even a small part of a sphere must distort the distances.

The Gauss–Bonnet theorem relates the total curvature of a surface to its Euler characteristic and provides an important link between local geometric properties and global topological properties.

There are other surfaces which have constant positive Gaussian curvature.

do Carmo also gives three different examples of surface with constant negative Gaussian curvature, one of which is pseudosphere.

Whilst the sphere is rigid and can not be bent using an isometry, if a small region removed, or even a cut along a small segment, then the resulting surface can be bent.