Halteres

[7][8] The nervous system can then transform the bending of these hairs into electrical signals, which the fly interprets as body rotation information.

V. Buddenbrock was able to show that immediately after haltere removal flies were unable to produce normal wing movements.

Further, in an interesting side experiment performed by Pringle (1938), when a thread was attached to the abdomen of haltereless flies, relatively stable flight was again achieved.

Using high speed video analysis, Faust (1952) demonstrated that this was not the case and that halteres are capable of detecting all three directions of rotation.

[13] In response to this new discovery, Pringle reexamined his previous assumption and came to the conclusion that flies were capable of detecting all three directions of rotation simply by comparing inputs from the left and right sides of the body.

[3] The sensilla are arranged in a way so similar to that of hindwings, that were the halteres to be replaced with wings, the forces produced would still be sufficient to activate the same sensory organs.

In fact, haltere development has been traced back to a single gene (Ubx), which when deactivated results in the formation of a hindwing instead.

[15] Though no other structure with entirely the same function and morphology as halteres has been observed in nature, they have evolved at least twice in the class Insecta, once in the order Diptera and again in Strepsiptera.

[17] Though strepsipterans are very difficult to locate and are additionally rather short-lived, Pix et al. (1993) confirmed that the specialized forewings that male Strepsiptera possess perform the same function as dipteran halteres.

Using functional morphology and behavior studies, Pix et al. showed that these sensors then transmit body position information to the head and abdomen to produce compensatory movements.

[18] A study performed using the hawk moth, Manduca sexta, confirmed that these tiny, antennal oscillations were actually contributing to body rotation sensation.

[15] Proper hindwing development in a number of insect species is dependent on Ubx, including butterflies, beetles, and flies.

[15] This single homeotic gene change results in a radically different phenotype, but also begins to give us some insight into how the ancestors of flies' hindwings may have originally evolved into halteres.

[23][24] Other genes which are expressed in wings and repressed in halteres have also been identified, but whether or not they act as direct targets of Ubx regulation are still unknown.

This means that the decoding mechanisms used by the central nervous system to interpret such movements and produce adequate motor output probably also vary depending on phylogeny.

More derived families, such as Calliphoridae (blow flies), have developed specialized structures called "calyptrae" or "squama", which are tiny flaps of wing, that cover the haltere.

Pringle (1948) hypothesized that they prevented wind turbulence from affecting haltere movements, allowing more precise detection of body position, but this was never tested.

[3] An extreme example of this trait is in the family Syrphidae (hoverflies), where the bulb of the haltere is positioned nearly perpendicular to the stalk.

[31] Haltere afferent activity responding to rotations and wing steering behavior converge in this processing region.

It has been determined that those five sensory fields all project to the thorax in a "region-specific" way and afferents originating from the forewing were also shown to converge in the same regions.

Unfortunately, as soon as it does, the halteres sense a body rotation and reflexively correct the turn, preventing the fly from changing direction.

Chan and Dickinson (1998) suggested that what the fly does to prevent this from occurring is to first move its halteres as if it were being pushed in the opposite direction that it wants to go.

Mureli and Fox (2015) showed that flies are still capable of performing planned turns even when their halteres have been removed entirely.

Chordotonal organs, unlike campaniform sensilla, exist beneath the cuticle and typically respond to stretch as opposed to distortion or bending.

When halteres were removed at the bulb (to retain intact sensory organs at the base) the fly's ability to perceive roll movements at high angular velocities disappeared.

[36] From this result it can be concluded that although halteres are required for detecting fast rotations, the visual system is adept by itself at sensing and correcting for slower body movements.

Responses to body rotations detected via the visual system are greatest at slow speeds and decrease with increased angular velocity.

The integration of these two separately tuned sensors allows the flies to detect a wide range of angular velocities in all three directions of rotation.

[33] This indicates that although halteres are not required for motion vision processing, they do contribute to it in a context-dependent manner, even when the behavior is separated from body rotations.

Certain flies in the families Muscidae, Anthomyiidae, Calliphoridae, Sarcophagidae, Tachinidae, and Micropezidae have been documented to oscillate their wings while walking in addition to during flight.

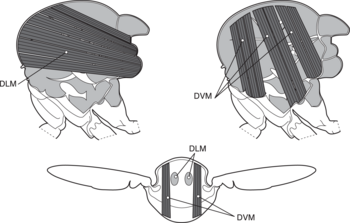

a wings

b primary and secondary flight joints

c dorsoventral flight muscles

d longitudinal muscles

1 calyptra (squama) 2 upper calypter (antisquama) 3 haltere 4 mesopleuron 5 hypopleuron 6 coxa 7 wing 8 abdominal segment 9 mesonotum c capitellum of haltere p pedicel of haltere s scabellum of haltere