Han Zhong (Daoist)

In Chinese history, Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China, commissioned Han in 215 BCE to lead a maritime expedition in search of the elixir of life, yet he never returned, which subsequently led to the infamous burning of books and burying of scholars.

In Daoist tradition, after Han Zhong consumed the psychoactive drug changpu (菖蒲, "Acorus calamus, sweet flag") for thirteen years, he grew thick body hair that protected him from cold, acquired a photographic memory, and achieved transcendence.

("Seven Remonstrances", Hawkes 1985: 245); "Floating on cloud and mist, we enter the dim height of heaven; Riding on white deer we sport and take our pleasure."

In 215 BCE, during Qin Shi Huang's fourth imperial inspection tour of northeast China, he commissioned more naval expeditions searching for Transcendental drugs.

First, when the emperor was visiting Mount Jieshi (碣石山, in Hebei) he commanded Scholar Lu (盧生), from Yan, to find the Transcendent Xianmen Gao (羨門高) (Needham 1976: 18).

When Lu came back from his unsuccessful mission overseas, he reported on "matters concerning ghosts and gods" to the emperor, and presented prophetic writings, one of which read: "Qin will be destroyed by hu [亡秦者胡也]."

Then, Scholars Lu and Hou secretly met and concluded that since Qin Shi Huang had never been informed of his mistakes, and was becoming more arrogant daily, his obsession with power was so extreme that they could never seek the elixir of longevity for him (Nienhauser 2018: 149).

Finally, in 210 BCE, the last year of Qin Shi Huang's life, Xu Fu and the remaining fangshi worried that the emperor would punish them for their failures to find longevity drugs, and made up a fish story.

Although the 2nd century CE Liexian Zhuan (Collected Biographies of Transcendents) does not mention Han Zhong, it records calamus as one of 29 psychoactive plants consumed by Daoist adepts (Chen 2021: 18–19).

This chapter quotes the apocryphal Yuanshen qi (援神契, Key to the Sacred Foundation) for the Classic of Filial Piety, "Pepper and ginger protect against the effects of dampness, sweet flag sharpens the hearing [菖蒲益聰], sesame protracts the years, and resin puts weapons to flight."

It also describes magical rouzhi (肉芝, "flesh excrescences"), notably the fengli, a mythical flying animal, "resembling a sable, blue in color and the size of a fox" found in southern forests.

It is almost impossible to slay, except for changpu suffocation, and cannot be killed by burning, chopping with an ax, or beating with an iron mace, but "It dies at once, however, if its nose is stuffed with reeds from the surface of a rock [石上菖蒲]" (11, Ware 1966: 185).

"The Ultimate System" chapter mentions ancient herbal cures about which people are skeptical, including, "sweet flag and dried ginger [菖蒲乾姜] check rheumatism" (5, Ware 1966: 103).

Ge Hong also compiled the c. 4th century Daoist Shenxian zhuan (Biographies of Divine Transcendents), which mentions Han Zhong in cases of two calamus-eaters.

There I saw a personage riding a carriage drawn by a white deer, followed by several dozen attendants, including four jade maidens each of whom was holding a staff hung with a colored flag and was fifteen or sixteen years old.

Campany 2002: 243-244) Han Zhong then summarized various methods of achieving xian Transcendence, the best of which will allow one to live for several hundred years, and said, "If you desire long life, the first thing you must do is to expel the three corpses.

Han presented Liu with a manuscript of the Shenfang wupian (神方五篇, Divine Methods in Five Sections), which says, The ambushing corpses always ascend to Heaven to report on people's sins on the first, fifteenth, and last days of each month.

I have heard that the sweet flag that grows atop rocks on the Central Marchmount here, the variety with nine joints [節] per inch, will bring one long life if ingested.

Only Wang Xing, who had overheard the transcendent instructing Emperor Wu to take sweet flag, harvested and ingested it without ceasing and so attained long life.

(Campany 2002: 341-342) The eminent Tang poet Li Bai (701–762) wrote "The Calamus-Gatherer of Mount Song" (嵩山采菖蒲者)", which refers to this Shenxian zhuan story about Emperor Wu of Han.

A divine person of ancient visage, Both ears hanging down to his shoulders, Came upon, on Song Marchmount, the Marshal One of Han, Who considered him a Transcendent of Mount Jiuyi.

Shangqing School tradition links Han Zhong with the provenance of several scriptures, such as the Taishang Lingbao wufu (太上靈寶五符, Five Talismans of the Numinous Treasure).

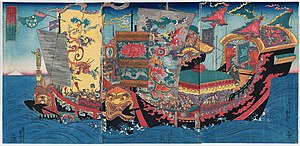

Some early accounts of Han Zhong, such as this Music Bureau poem, refer to his iconographic white deer, which he usually rode or sometimes hitched to a flying chariot.

Later hagiographies add information that Han Zhong was a native of Deyang district (modern Chengdu, Sichuan), studied the Dao with Tianzhen huangren (天真皇人, August One of Heavenly Perfection), transmitted the Shangqing jinshu yuzi (上清金書玉字, Golden Scripture with Jade Characters), and at the end of his life ascended to heaven in broad daylight (Campany 2002: 243).

Preparations, including calamus powder, juice, and tincture are used to treat hemoptysis, colic, menorrhagia, carbuncles, buboes, deaf ears, and sore eyes (Stuart and Smith 1911: 14).

(Bokenkamp 2015: 298) Praised as a (lingcao (靈草, "celestial herb") in Daoist texts, the calamus was believed to increase longevity, improve memory, and "heal a thousand diseases" (Junqueira 2022: 458–459).

The above Baopuzi description of Han Zhong eating changpu for thirteen years states that the best variety has zihua (紫花, "purple flowers"), which is obviously not the sweet flag.

In the marshy spots near the eastern mountain streams [of Mao Shan] there is a plant called the Brook Iris 溪蓀, which, in root shape and appearance is exceedingly similar to the calamus which grows on stones.

During the Dragon Boat Festival, a ubiquitous ritual in traditional Chinese households consisted of hanging up mugwort twigs and calamus leaves, tied with a red thread, above the front door, in order to ward off evil.

The Dragon Boat Festival doucao (闘草, "battle with herbs") observance may well have originated as a demon-quelling sword in some sort of religious drama (Junqueira 2022: 459).