Tao Hongjing

Tao Hongjing (456–536), courtesy name Tongming, was a Chinese alchemist, astronomer, calligrapher, military general, musician, physician, and pharmacologist during the Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589).

The British sinologist Lionel Giles said Tao's "versatility was amazing: scholar, philosopher, calligraphist, musician, alchemist, pharmacologist, astronomer, he may be regarded as the Chinese counterpart of Leonardo da Vinci".

However, Gao's successor, Emperor Wu of Southern Qi (r. 482–493), appointed him as tutor for his son prince Xiao Jian (蕭鏗, 477–494) in 482, and designated him as General of the Left Guard of the Palace in 483.

[6] During the period of mourning for his mother from 484 to 486, Tao Hongjing studied with the Taoist master Sun Youyue (孫遊岳, 399–489), who had been a disciple of Lu Xiujing (陸修靜, 406–477), the standardizer of the Lingbao School scriptures and ritual.

In 514, Xiao Yan ordered the Zhuyang guan (朱陽館, Abbey of Vermilion Yang) state-sponsored hermitage to be built on Maoshan and Tao installed himself in the following year.

[11] The emperor kept up a regular correspondence with Tao, often visited Maoshan to consult on important matters of state, and gave him the title Shanzhong zaixiang (山中宰相, "Grand Councilor of the Mountains").

[12] Between 508 and 512, Tao journeyed throughout the southeast, in the modern provinces of Fujian, Zhejiang, and Fuzhou, in order to continue making alchemical experiments in the mountains.

"pottery") is fairly common and his given name combines hóng (弘 "grand; magnificent; vast") and jǐng (景 "view; scene, scenery").

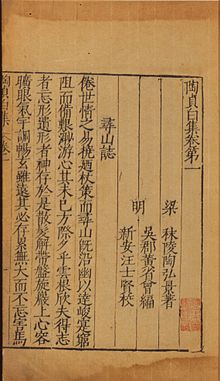

[16] Tao Hongjing's literary career began at the age of fifteen with his 471 fu-like Xunshan zhi (尋山志, "Rhapsody on Exploring the Mountains").

[7] Some architectural elements from Tao's tomb, discovered on Maoshan during the Cultural Revolution, bear an inscription calling him "a disciple of the Buddha and of the Most High Lord Lao[zi]".

From 483, Tao became interested in the Shangqing revelations granted to Yang Xi more than a century earlier and decided to collect the original autograph manuscripts, using calligraphy as one of the criteria to establish their authenticity.

now-lost Zhenji jing (真跡經, "Scripture on the Traces of the Perfected"), an earlier but in Tao's view unsatisfying account of Yang Xi's revelations.

Moreover, the Shangqing revelations inspired Tao to compose a commentary to one of the texts received by Yang Xi, the Jianjing (劍經, "Scripture of the Sword"), which is included in the Taiping Yulan.

[17] The sinologist Roger Greatrex describes Ge Hong and Tao Hongjing as "early scientists" who made numerous observations of natural phenomena, which they attempted to accord with the Five Elements theory.

[18] Tao's preface explains that beginning in the Wei-Jin period, copies of the Shennong bencao jing text had become corrupted, and contemporary medical practitioners "are not able to clearly comprehend information and as a result their knowledge has become shallow".

[26] He further explains that his commentary combines previous material from the Shengnong bencao jing (which Tao refers to as Benjing) and other early pharmacological sources, material from his Mingyi bielu (名醫別錄, "Supplementary Records of Famous Physicians"), and information gathered from alchemical texts, notably what he calls xianjing (仙經, "classics on immortality elixirs") and daoshu (道書, "books on Daoist techniques").

While the early pharmacopeia had only graded substances into superior, medium and inferior, Tao rearranged them into a classification that continues to be used today: minerals, trees and plants, insects and animals, fruits, cultivated vegetables, and grains.

[27] Tao is considered "the effective founder of critical pharmacology in China", and his editions and commentaries were "painstaking productions, using, for example, different colored inks to distinguish text, original annotations, and his own editorial additions".

[17][29] In 497, Emperor Ming assigned Tao Hongjing to experiment with sword foundry, and provided him with an assistant, Huang Wenqing (黃文慶) a blacksmith from the imperial workshops, who became a Shangqing initiate in 505.

"outer alchemy", preparing herbal and chemical elixirs of immortality), and studied several methods that he successively discarded because of unavailable ingredients, even with imperial support.

Tao blamed these failures on the lack of genuine isolation, since Maoshan had a large community of permanent residents and their families as well as numerous visitors on pilgrimages.